Nostalgic Poetry Challenge

The 2025 Society of Classical Poets International Poetry Competition

The 2025 SCP International High School Poetry Competition

The Best Haiku of 2025: Winners of the 2025 SCP Haiku Competition

Inspiring Muse Poetry Challenge

A Video Reading of ‘Late Bloomers’ by Cynthia Erlandson (SCP Symposium)

The poem read by the poet herself at the Society of Classical Poets' in-person Poetry Symposium held in Naperville, Illinois...

A Video Reading of ‘Ode to the Dogs’ by Shari Jo Lekane

. The poem "Ode to the Dogs" by Shari Jo Lekane read by the poet herself at the Society of...

A Video Reading of ‘May Memorial’ and Other Poetry by Cynthia Erlandson

. The poem "May Memorial" by Cynthia Erlandson read by the poet herself at the Society of Classical Poets online...

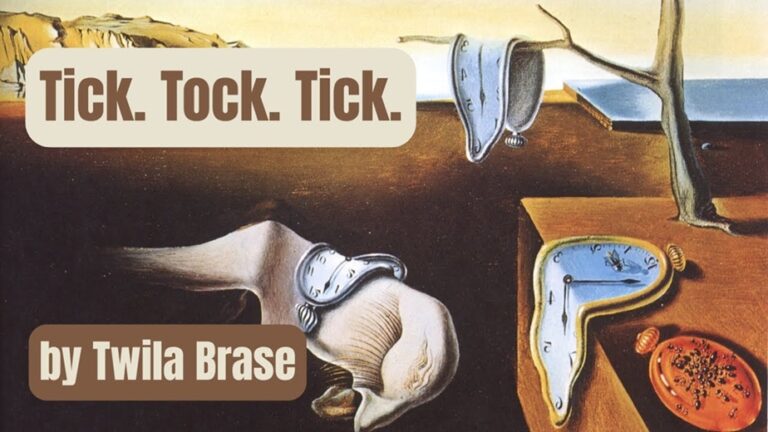

A Video Reading of the Poem ‘Tick. Tock. Tick.’ by Twila Brase

. The poem "Tick. Tock. Tick." by Twila Brase read by the poet herself at the Society of Classical Poets...

‘Harry Thurston Peck’: An Essay by Joseph S. Salemi

Harry Thurston Peck by Joseph S. Salemi A few weeks ago my wife asked me to find a book...

‘Form and Worldview in Classical Chinese Poetry’: An Essay by Adam Sedia

. Harmony of Design: Form and Worldview in Classical Chinese Poetry by Adam Sedia China’s uninterrupted literary tradition of three...

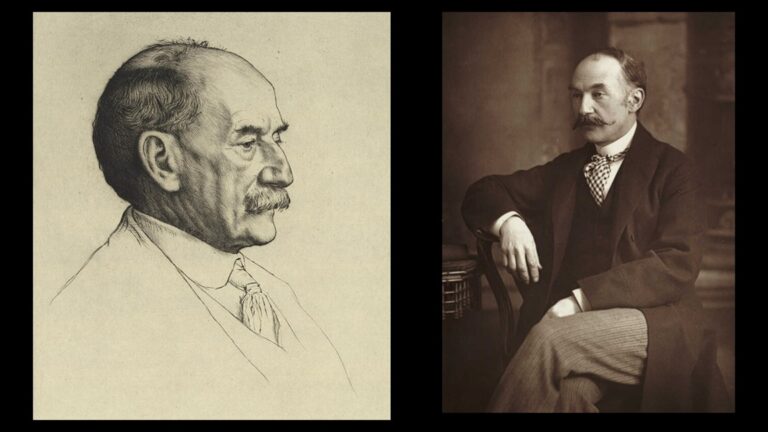

The Poetry of Thomas Hardy: An Essay by Adam Sedia

. A Poet First: The Poetry of Thomas Hardy by Adam Sedia Thomas Hardy (1840-1928) is known today primarily as...

‘Poetry as a Pathway to Critical Thinking’: An Essay by Leland James

. Poetry as a Pathway to Critical Thinking —with a focus on metaphor and image Poetry: “the right words in...

‘Longfellow’: A Poem by Kevin Parks

Longfellow I first met you in the schoolroom, _When I was but a child, And read your words and...

Three Short Poems by Heinrich Heine, Translated by Josh Olson

Three Short Poems by Heinrich Heine translated from German by Josh Olson 1 I laugh at every doltish...

The Best Poems of 2024: Winners of SCP International Poetry Competition

. The Best Poems of 2024: Winners of the 13th Annual SCP International Poetry Competition Judges C.B. Anderson, Susan Jarvis...

The Ten Best Poems to Analyze

. The Ten Best Poems to Analyze by Adam Sedia The Roman poet Horace famously set forth the twofold purpose...

10 Poems on Builders & Buildings

10 Poems on Builders & Buildings by Michael Curtis . Temples and architects, builders and buildings are like poets and...

The Best Poems of 2023: Winners of SCP International Poetry Competition

. The Best Poems of 2023: Winners of the 12th Annual SCP International Poetry Competition Judges Joseph S. Salemi, James...

The 10 Best Poems of Emily Dickinson

. The 10 Best Poems of Emily Dickinson by Monika Cooper Being presented with an Emily Dickinson poem is like...

‘Europe Arranges Its Own Autopsy’: A Poem by Brian Yapko

. Europe Arranges Its Own Autopsy ---with apologies to T.S. Eliot . I. The Trojan Horse When April came it...

‘Vera Crux’: A Poem by Joseph S. Salemi

Vera Crux Vera Crux is Latin for “True Cross,” and is the source of the name of the Mexican...

Nostalgic Poetry Challenge

This poetry challenge comes from poet Roy E. Peterson: From your past, write and provide us a poem about something...

‘Lotus’: A Poem by Margaret Coats

Lotus First flower, from primeval flooding sprung, In virtuous, voluptuous perfection, The lotus favors eye and mind and tongue With...

‘Snootsplaining’: A Poem by Susan Jarvis Bryant

Snootsplaining For every galoot there’s a dutiful snoot Acutely aware that their truth’s absolute. They jabber and jaw as...

‘The Candy Bandits’ and Other Halloween Poetry by Susan Jarvis Bryant

The Candy Bandits They’re heartless and artful---delinquents of wit With grab-happy claws and a glare that is lit With...

Discussing Now