“Look not on the face, young girl, look at the heart.”

—Quasimodo, The Hunchback of Notre Dame

A vile, lumbering mass, so hideous,

Rejected and despised by every eye

That fears and is repulsed by odious

Perversions of our kind. You horrify

And shock the average sensibility

For which all imperfection is rejected

And avoided. You are ugliness,

A limping lump of flesh. How you are affected

By the body of your wretchedness!

But souls, come look beyond the skin

And see a difference from within the heart!

Quasimodo, you are kind within

Your stricken, broken body. Counterpart

To your condition is this rarity

Of spirit and mind. Embodiment of good,

Self-sacrifice, compassion—for the love

That gives all from a place of charity

In spite of every pain is understood

To form within as well as from above.

It only took a single, cooling cup

Of water, but you drank with thankfulness;

And as La Esmeralda lifted up

Your sorry head, you looked with gratefulness

To one who chose a good deed on the day.

Oh, how this changed your lonely, saddened state

To gratitude and love from emptiness—

For now you loved her. Banished and away

All forms of mockery—a better fate

Because your form was touched by loveliness.

And then what? In her time of utmost need

You aided her. You rescued her, you saved

Her, sheltered her, protected her. Indeed

You gave back hundredfold for what she braved

In giving you that drink. But all in vain;

The gallows waited for her neck. You tried

To keep her from her date with hungry death

But all for naught. For you could not obtain

Her liberty. You watched her as she died,

And let a howl out with woeful breath.

You cried and no one heard your bitter groans,

But ’round your love were found your noble bones!

Theresa Rodriguez is the author of Jesus and Eros: Sonnets, Poems and Songs, a chapbook of thirty-seven sonnets, and Longer Thoughts (Shanti Arts, 2020). She is a retired classical singer and voice teacher who has written for Classical Singer magazine. She recently released an album entitled Lullabies: Traditional American and International Songs which is available on all streaming services.

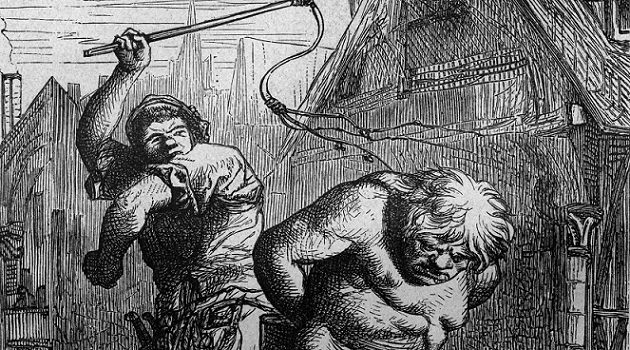

Thank you Evan, for the excellent illustration to go with the poem. I was inspired to write this ode to Quasimodo after the Notre Dame Cathedral fire in the spring. The novel is one of my favorite books of all time!

Beautiful, Theresa! Thank you.

Leo

You are very welcome Leo, I’m glad you liked it!

Very beautiful, yes, thank you, Theresa.

You’re welcome James, so glad you liked it!

What’s odd about this is that it’s a text about other text. Or it’s a text about how the writer is affected by other text, as opposed to about [real] life.

Of the richness of life and nature, I’m just wondering how deep[ly] you can go when a piece of writing is about the emotions triggered by another piece of writing. That stage (arena) would be limited to and by the imagination, and I’m not sure how much room there is for real discovery. So the arena here is more mind than heart, or if it’s heart, it’s the heart that’s conjured up by the mind. Not that feelings about fiction aren’t real, but they’re real once or twice removed from reality.

I’ve seen excellent work by you, Theresa, and I’m just looking for [wondering] why this doesn’t meet up to it.

And you may also say that this post therefore is a piece of text about text that’s about text. And if you comment on this comment, it will be text about text about text about text. And so on.

Many literary works are about other earlier literary texts. There is even a cliche about the phenomenon in contemporary criticism — the thing is called “intertextuality.” Virgil’s Aeneid is clearly a deliberate riff on Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey; Milton’s Paradise Lost does the same with the Book of Genesis; and God only knows how many writers have used Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes as a character in their own independent works.

Your dichotomy of “mind” and “heart” is not useful, and betrays an Romantic mindset. Literature is the creation primarily of intelligence, wit, verbal fluency, and rhetorical tropes and figures. Everybody has “heart.” Only the gifted few have the other things.

Hi Paul, whilst it is true that Theresa may have written better poems, and my review of two of her books on SCP is due this month, so see that for more, yet your other point is, I think, contentious; for we can empathise and identify with fictional characters in the same way we can with real ones. Indeed, in one sense dead historical characters are like fictional characters in that they are not physically present. But if I take Odysseus or Prospero, or seek to respond to the marvellous Abdiel in Book 5 of Paradise Lost, I find my emotions aflame. Yet … yet … I take your point: there is really nobody quite as inspiring as my real wife! Suffice to say, then, I think Theresa’s methodology sound, though it may not appeal to everyone in the way writing about a ‘real’ person might.

Paul, Your comment is a miasmal mix of sense and nonsense that I found most amusing. I immediately thought of Samuel Time or Coleridge’s opium-induced poem, Kubla Khan, a clearly imaginative, fantasy involving a historical character. Does Kahn, being historical, provide a more legitimate basis for an empathetic poem than Quasimodo? Is a portrait of Aristotle to be considered more authentic and legitimate than one depicting Hamlet holding the skull of “poor Yorick” or the Fall of Icarus? Is the “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” less of a poem than the “Charge of the Light Brigade” because one involves real people and one does not?

The emotions and issues related to our common humanity that Theresa explores so movingly in her poem re Esmeralda and the “Hunchback of Norte Dame” are every bit as “real” and “true” as one might find in an equally inspired attempt to write a poem based on what Marie Antoinette may have been feeling as she mounted the scaffold and placed her head beneath the blade—a poem whose subject matter would interest me far less than that ofTheresa’s. Thanks for the smile.

Well said, James (and the same to the other James, above). All writing is a commentary on one thing or another, and no matter how far removed from the original figure or how ekphrastic the work might be, the important thing is the feeling it evokes in the reader. But I DO wish that Theresa would quit trying to rhyme “-ness” with “-ness.” I’ve tried to explain, several times, on this site why the practice is a bad one, but it seems that no one has paid much attention. To reiterate, its like trying to rhyme “-ly” with “-ly,” where the prior syllables do not rhyme at all. For example, “comely” rhymes with “dumbly,” but “lovely” is not a good rhyme with “slovenly.” “Thankfulness” is a poor rhyme with “gratefulness,” but “platitude” goes well with “gratitude.” And so forth.

Thanks, all – for your reflections on my notion that a poem about a text might somehow be less. Actually, about the contents of a text.

I myself feel the most important issues in [generating] a poem are the language, music, sound, playfulness, and its general and specific aesthetics, regardless of its content. So I myself should feel it shouldn’t matter whether the subject is in the world or in another’s writings.

So you all seem to be saying that our relationships with things depicted in others’ texts are as rich – insofar as influencing our poems – as our relationships with things in the world. How can that be? I can see being moved by others’ writing – even by its contents – but that can only be a one-way relationship.

I have no final position here. I’m just tossing this around, exploring it.

Dear Mr. Oratofsky —

I understand what you are saying. And yes, a mutual relationship between living human beings is more powerful (and ultimately more important) than a fictionalized relationship between texts, or our aesthetic enjoyment of texts.

But the essence of literature (and all the arts, whether verbal or plastic) is that they are the furniture of what I call “a licensed zone of hyper-reality.” This means that they exist on their own terms, only tangentially connected to what we call “real life.” They need not follow any laws, or obey any morality, or act in ways that we would expect a human being to act. They are purely imaginative constructs, and can only be judged on how well they entertain us or move us.

That’s why literary texts can be about other literary texts, or about utterly unreal situations, or about purely imaginary characters and places. They are examples of “fictive mimesis,” which means “not real life, but a made-up imitation of life.” Or to put it more simply, literature is artificial.