.

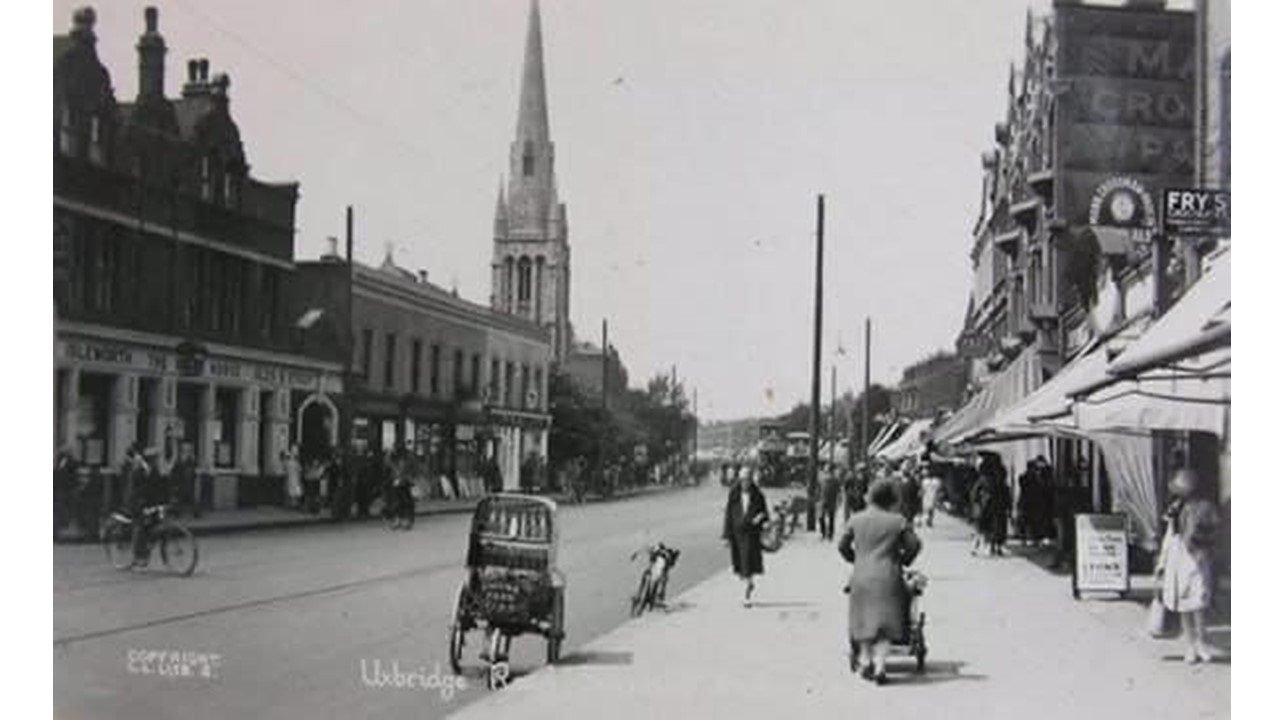

The Number 207: The Road

to Nowhere

Oh once along the Road to Nowhere

That used to be the Uxbridge Road

You’d board and pay the tuppenny bus fare

And go where milk and honey flowed.

For this was then a demi-Eden

Where gentlefolk would take their ease.

With Adam in an English season

You’d walk content beneath the trees.

And everyone was someone’s neighbour:

You knew the other’s name to chat.

When Mrs. Jones went into labour

You’d go around and feed her cat.

You shared a common English language;

And history, too, to make you proud.

You’d take to work for lunch a sandwich

And never play your records loud.

You’d listen to the radio;

You’d tune the dial to hear the news.

You’d dream of buying a bungalow,

Or save to get some natty shoes.

And when in love you’d whisper shyly,

And as a child play hide and seek.

When grown-ups talked you’d listen quietly:

You’d wait your turn for when to speak.

Your world possessed a settled order

Where all belonged and had a place,

And being deprived or someone’s boarder

Was never thought to bring disgrace.

You had a shared identity

Which bound you in a common cause.

Secure from foreign tyranny,

Your rulers ruled through ancient laws.

And you were England, born and bred,

Aware of all the debt you owed.

For many souls you knew had bled

To live in you on Uxbridge Road.

But that was then and this is now,

And all such halcyon days are passed.

There is though this, if you’ll allow:

For traffic jams it’s unsurpassed.

.

.

Paul Martin Freeman is an art dealer in London. The poem is from The Bus Poems: A Tale of the Devil, currently in preparation. His recent book, A Chocolate Box Menagerie, is published by New English Review Press on whose website the current poem first appeared.

Oh, yes. Many’s the time I caught the 207 on the Uxbridge Road. You’d wait hours and they would usually come in threes.

Lol Same thing with the #32 on Edinburgh’s Princess Street back in 1978. Always late, always in threes, and because everyone boarded the first and second bus the third one always made the rounds empty.

Paul,

A non-maudlin mini-masterpiece of pithy, witty, melancholy retrospective reminiscence.

“Gee our old LaSalle ran great. Those were the days.”

Thank you. That’s very kind.

That seems like the road to somewhere idyllic, but as with all such places that linger in our memory, those days are gone with urbanization and unpleasant social changes. Your poem was an enjoyable read that gave me insight into a more tranquil time and place that I would like to have personally known. Wonderful cadence and rhyme.

As always, thank you, Roy, for your encouraging comment.

This poem brought back memories of neighborhoods I grew up in; places where you did know your neighbors and spoke to each other. In many ways we’ve lost that sense of community. Today you can live on the same street, yet never engage with the people who live just two houses down.

Back in the day, I get the feeling we needed each other more. For instance, our neighbour two doors down, a plumber, fixed our blocked drains one summer, and my dad and he cut down the elm tree in his garden that was suffering from Dutch elm disease (my dad felled infected trees for a living during a period of unemployment).

I wrote a short story a little while back about two neighbours living in poverty in council flats who end up helping each other out through English lessons for a child in exchange for a meal. On the one hand it was depressing because of the poverty, but on the other hand there was the inkling of a budding romance between the lonely neighbours. It was interesting to see the readers’ take on that story.

So maybe, with today’s economic climate, the feeling of community will come back again through mutual need.

Humanity, like a little flower growing out of a wall, often manages to break through in the most unlikely of circumstances.

Indeed, Cheryl. I suspect it’s got worse for those of us who live in big cities. But I don’t feel for many it was ever as rosy or as simple a picture as I’ve drawn. I think I was trying to create a myth, albeit one rooted in our common experience.

Thank you for commenting.

Very well done. We seem to worship change as a society but most change doesn’t seem to be for the better.

Thank you, Warren. I think you’re right, we do worship change, which is not always for the better. Certainly, as a confirmed stick-in-the mud, any change which requires me changing is NEVER for the better!

It’s remarkable how a remembered place from the past can persist, and serve to inspire composition. Our strongest memories are from childhood, and the neighborhoods and locales where we dwelt. This is why the older “memory systems” (patterns for mnemonic devices) depended heavily on a person’s recollection of the rooms of a house, a series of streets or lanes, or the sections of a village. These “place memories” were deeply imprinted in the visual recall of one’s childhood, and could serve as a structure on which to attach things to be memorized.

In this poem, the “place” is used to summon up remembrance of a different mode of living.

Thank you for your comment. The main story in the book describes the visit to London of the Devil, bringing Milton’s story up to date. In this and one or two other poems, that mythical England which later lost its identity is intended as a metaphor for Eden.

At least, I think that’s what I was doing!

Paul Martin, I think you’re doing more than you know. An anthropologist, from whom I have learned a great deal, says that human beings have a nostalgia for paradise as part of the human condition. However different paradise may be from reality, it is the only place to live a fully human life. Therefore every culture has its rituals of remembering and reconstructing or rediscovering Eden, even if only in a small way (tea in a beautiful back garden, observing a holiday, visiting a shop with a friendly proprietor, cheerfully helping one’s neighbors–as in your story). Your delightful poem offers paradise to the minds of readers. It renews my ideals in thinking of England, even though I have visited numerous times and seen the “now” up close. I can live in that England like your little flowers growing out of the wall. The real tragedy of modern inhuman life is that so many prefer bitterness, resentment, badmouthing paradise, destroying whatever bits of it they find, and screaming at others that it is unattainable. Even these individuals still look for it, usually in some form of unhappy and unhealthy tyranny. You paint a picture of it, easy enough to find by reading a book, or maybe riding a bus. Good for you!

Thank you for your very interesting comment, Margaret. We must indeed keep hope alive as without it we are lost.

I hope you will come to England again.

Well written. Of course there is always a tendency to idealise the past: but as a fellow Brit, I too miss a lot about the UK of decades ago. And I’m heartily fed up with being told that there is nothing in Britain’s history except slavery, racism, etc.

Thank you for your comment, David. As I’ve indicated above, in the book of which it is part the poem is intended to mythologize England’s past into a metaphor for lost Eden. I probably had in my head somewhere John of Gaunt’s speech.