by Sultana Raza

In April 1820, Keats was already aware that he had tuberculosis, and in spring of that year, he was experiencing fever, a bad chest, and lots of anxiety, specially about not being able to finish his poems, and that he would remain obscure. He’d previously nursed and watched his mother and brother Tom die because of TB. Being a surgeon’s assistant, he knew what to expect when his turn would come. Many of his poems explore the idea of death, and (im)mortality such as “When I Have Fears That I May Cease To Be,” where perhaps the last three lines are most relevant to us now, as many people are obliged to search for the meaning of their own lives:

…then on the shore

Of the wide world I stand alone, and think

Till love and fame to nothingness do sink.

In his short poem, “On Death,” possibly written to comfort his brother Tom, whom he was nursing from TB, (unknowingly) Keats took quite a Buddhist view of mortality:

Can death be sleep, when life is but a dream,

And scenes of bliss pass as a phantom by?

The transient pleasures as a vision seem,

And yet we think the greatest pain’s to die.

How strange it is that man on earth should roam,

And lead a life of woe, but not forsake

His rugged path; nor dare he view alone

His future doom which is but to awake.

Could the above words bring solace to those at risk in the current epidemic too? Many are facing financial loss and ruin, a subject that Keats was painfully familiar with no less due to the rise of industrialization in the early 1800s. These images from “Ode to a Nightingale” could be apply to millions across the world today, whose lives have been interrupted by the coronavirus epidemic:

The weariness, the fever, and the fret

Here, where men sit and hear each other groan;

Where palsy shakes a few, sad, last gray hairs,

Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies;

Where but to think is to be full of sorrow

And leaden-eyed despairs…

Due to his medical training, Keats was all too knowledgeable with the diseases of the day. Can these words from “Ode to a Grecian Urn” ring true for those struck by the new virus?

That leaves a heart high-sorrowful and cloy’d,

A burning forehead, and a parching tongue.

Although Keats is describing a fictitious town in ancient Greece, this word painting from “Ode to a Grecian Urn” eerily echoes the state of some small towns and villages these days due to the lockdown:

And, little town, thy streets for evermore

Will silent be; and not a soul to tell

Why thou art desolate, can e’er return.

Especially if the economies of some tiny villages are destroyed, due to the enforced closure of small businesses.

Cases of social isolation were not isolated in the 1800s, particularly for women. Keats was well aware of these kinds of restrictions, as he wrote a poem, “Hush, Hush Tread Softly,” wherein he fantasized about running away with a girl, presumably the mysterious Isabella Jones, whose movements and liberty were quite restricted, as she lived with an older man, on the edges of society. Encouraged by Isabella Jones, Keats produced “Isabella, or the Pot of Basil,” wherein Isabella puts herself in confinement, mourning the head of her lowly lover, Lorenzo.

And she forgot the stars, the moon, and sun,

And she forgot the blue above the trees,

And she forgot the dells where waters run,

And she forgot the chilly autumn breeze;

She had no knowledge when the day was done,

And the new morn she saw not: but in peace…

During the current pandemic, high risk individuals, specially senior citizens are unlikely to venture outside, especially if they don’t have any help, and may well be experiencing Isabella’s self-imposed quarantine. Perhaps this poem also expresses Keats’s desire to rise above ignominy. Just like how the head of Orpheus was preserved by water nymphs in Greek myths, so is that of Lorenzo by Isabella. Perhaps one of Keats’s wishes was that the flesh and blood Isabella Jones would preserve the outpourings of his prodigious head.

Since Keats knew he would exit this world soon enough, he tried to see his only sister, Fanny from time to time. However, she was kept in confinement under the strict eye of her guardian, Richard Abbey (until her arranged marriage), to the extent that she wasn’t even allowed to see John one last time before he left for Rome in autumn 1820.

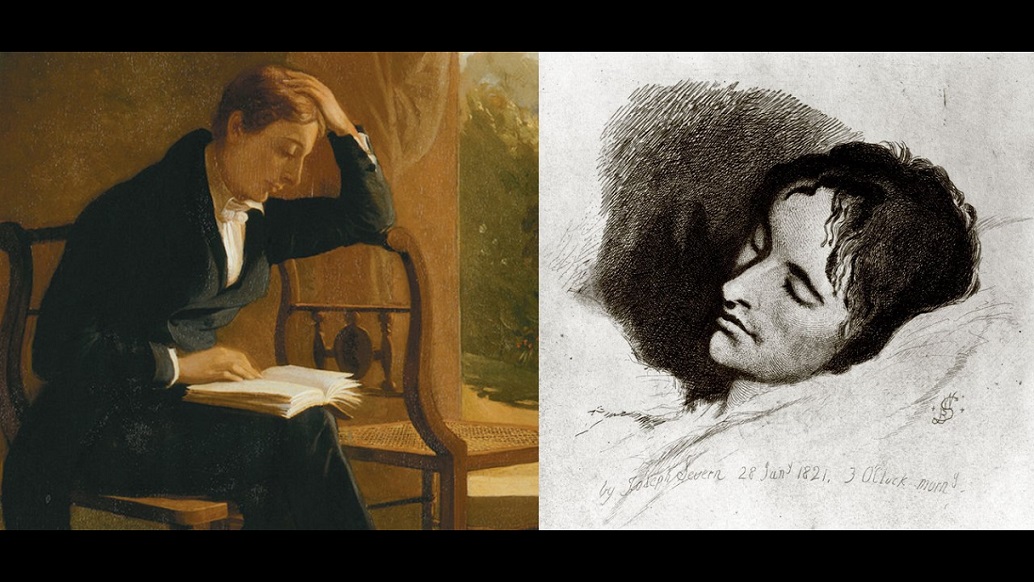

Having been deemed to be one of the Cockney School of poets, Keats (and most of Leigh Hunt’s circle) had suffered from social ostracization. So Keats was quite familiar with being left on the side lines of “polite” (read wealthy) society, as well as by the literati of those times. On his long sea voyage from England to Rome, he suffered from being squeezed into cramped quarters with the painter Severn and another very sick, TB infected young lady. Furthermore, he also got to experience a quarantine of ten days when his ship the Maria Crowther got stuck in the Bay of Naples on October 21, 1820. Even though he’d been “half in love with easeful death,” when he penned “Ode to a Nightingale,” little did he know that he would spend most of his time in the ancient and fascinating city of Rome, isolated in a small room for about three months, where he would lead an agonizing “posthumous existence” until his death on February 23, 1821.

Possibly, many of us can relate to the term, “a posthumous existence” during this period of enforced isolation, specially those who are used to socializing both at work and in their spare time. The more the focus on one’s career, the more difficult it is to accept this state of idleness, specially as fears of losing one’s livelihood rise with every passing quarantined day. At the same time, in this world where material possessions are much more important than peace of mind, and where quantity seems to matter more than quality, it’s quite difficult for most be in a state of “Negative Capability.” Keats defined it as “capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after facts and reason.” It seems this state of mind would be most conducive to dealing with the limbo that the gelling of social interactions has induced since April 2020.

Convalescing in Rome

Supposedly convalescing in Rome, Keats was put on a starvation diet, and was denied any opiates such as laudanum, which could have provided relief from pain. Given the policies of those ruling the world perhaps it’s not surprising that nearly two hundred years later, thousands of people are not getting adequate medical treatment for the deadly coronavirus. What could these thousands of people across various cultures have in common with Keats?

Perhaps the disturbing thought of their own mortality and obscurity, hence the unparalleled success of social media which has handed anyone and their dog the opportunity to shout from their virtual roof-tops about themselves and their mundane activities. They don’t mind if the police, secret services, or marketing companies are tracking their every move. At least someone is preserving their selfies somewhere. Though Keats’s name is not “in water writ,” and will continue to swim down the river of time, will the masses have more sympathy for him now that they’re faced with the spectre of sharing a similar fate as the young genius?

The vacuum left by Keats in poetics due to his early death has resounded down two centuries at least. Critics can’t help speculating what he’d have written about, had his been an average life span. Towards the end of 1820, and beginning of 1821, Keats would be struggling to breath in the confines of a tiny room in Rome, next to the vibrant Spanish Steps. Little would he have guessed that millions of Italians, would be quarantined due to a pandemic almost two hundred years later, which affects the lungs. The rest of Europe, along with the British, would follow soon. Would he have been comforted by this thought? Or would Keats, who’d qualified to be an apothecary’s assistant have wished that a cure would be discovered soon for this deadly new virus? Though a cure for TB has been found, unfortunately it was too late for him and his family.

Yet, should we rush to get a vaccine as soon as one is put on the market? What side effects might such a vaccine cause? Would Big Pharma even care about side effects, as long as any side effects generated even more income for them? The Regency period was as much a time of change and upheaval, with Habeas Corpus being suspended for a short while then. The 2020s would seem to bring a sea of change with the coronavirus following hot on the heels of Brexit for the British.

Yet, in that change lies the best opportunities to shake off unwanted and unnecessary shackles of consumerism and degeneration of traditional moral values, to lead a simpler life ruled by the core principles of humanity. We can delve into our own psyche to better understand ourselves, as alluded to in Keats’s “Ode to Psyche.” As Keats said in “Ode to a Grecian Urn”: “Truth is Beauty, beauty truth.” That is all we need to know. And to find both within ourselves—especially during the lockdown, when we have ample time to reflect upon it.

Note: this version was re-edited by Evan Mantyk on 17-5-2020

Further comments were added by Sultana Raza also on 17-5-2020.

Sultana Raza has presented many papers related to Romanticism and Fantasy in international conferences. Her 100+ articles (on art, theatre, film, and humanitarian issues) have appeared in English and French. Her creative non-fiction has appeared in Litro, and A Beautiful Space. Her fiction has received an Honorable Mention in Glimmer Train Review (USA), had been published in Coldnoon Journal, Szirine, apertura, Entropy, and ensemble (in French). Her poems have appeared in 30+ Journals, including Columbia Journal, and The New Verse News, London Grip, Gramma, Columbia Journal, Classical Poetry Society, spillwords, and The Peacock Journal.

This article not only fails to make Keats “relevant,” but reminds us that Romanticism is the very death of poetry. The world can be thankful that the godless, self-centered Keats died when he did.

Dear Mackenzie,

I recommend reading this article on Keats’ Great Odes, written by another poet in his own right, Daniel Leach.

https://www.thechainedmuse.com/single-post/2019/04/01/KEATS%E2%80%99-GREAT-ODES-AND-THE-SUBLIME

As Leach demonstrates, Keats’ poetry was very different from that of the ”Romantics.”” A clear distinction in approach and outlook can be made between the poetry of Byron, Wordsworth, Coleridge et al and that of Keats (and Shelley). Keats is one of the most talked about poets, but it’s arguable that he’s also one of the least understood; and I think anyone who gives the Odes an in depth read, regardless of their ideological or religious background, can discover that.

The Odes represent a series of nested paradoxes, and that expressed in arguably one of the most difficult and dense forms. The Keats Ode form hearkens back to the Canzone form of Dante, and even manages to advance it in some respects.

I think anyone who reads the essay above will agree it is not Keats who fails as a poet, but rather it is those who are not able to appreciate or ”grok” the Odes, who fail as serious readers.

Hope you are all well and safe.

Best,

David Gosselin

Mr Gosselin, thank you for the link to Daniel Leach’s essay, which manages to cover all his great odes. I agree that Keats’s poetry was quite different from that of the other Romantics, and with your remarks:

“Keats is one of the most talked about poets, but it’s arguable that he’s also one of the least understood;…”

“The Odes represent a series of nested paradoxes, and that expressed in arguably one of the most difficult and dense forms.”

Indeed, these are some of the reasons why scholars are still exploring new elements in Keats’s poems. For example, in the Keats Foundation Conference of 2017, Theresa M. Kelly’s brilliant paper on ways of looking and variations of scale in Keats’s poetry cast a fresh angle at even his early poems, such as the long and unwieldy Endymion. As scholars are beginning to dive into that poem, they are likely to discover new gems in his early efforts as well. Another growing area of study is that of examining the political aspects of his poems, such as this one:

https://beckassets.blob.core.windows.net/product/readingsample/336324/9780521651264_excerpt_001.pdf

Keats’s letters have been studied as well, and some give further insights into his inspirations, ideologies, concepts (such as ‘negative capability),’and creative process as well, (though not as much as one would have liked of course). Here’s an analysis of one of Keats’s letter by Greg Kuchich of the poet’s association with Leigh Hunt, editor of the radical newspaper, The Examiner:

http://keatslettersproject.com/correspondence/an-era-in-my-existence-the-season-of-mists-and-mellow-fruitfulness/

Great post and well measured in the times of Covid-19. Keats must have nursed poor Tom into December 1818 without a thought about PPE or anything remotely similar.

Thanks Ian Reynolds. Indeed, John nursed both his mother, and later on his brother Tom. John felt guilty about leaving Tom behind when he went away on a tour of Scotland with Brown with the hopes of igniting his own poetry, but fell ill on that strenuous tour, and had to return. Before he could recover himself, he had to start nursing Tom as from October 1818. You’re right to raise the point that since they didn’t have any self-protecting gear, health care workers and families did put themselves at great risk when taking care of TB patients, for example.

We know of John Keats as the poet who died so young and sick. Before he fell ill, though, he walked 600 miles through Scotland in the summer of 1818, in good and in foul weather, including a climb to the summit of Ben Nevis, the highest peak in the British Isles. Ben Nevis is not one of our world’s high mountains, reaching just 4,409 feet above sea level—but Keats started off from Fort William, located in the Great Glen, and the town’s elevation is no more than 150 feet. Four thousand feet of elevation gain makes for a full day.

I cimbed Ben Nevis some years ago, and found the peak in cloud. I could see no more than fifty yards. On the top I sat down on long flat rocks along with two dozen other hikers. I had finished my sandwiches and was wondering whether I was going to run out of water on my way down, when a wind came up and suddenly the cloud was gone.

The view was spectacular. Four thousand feet below us the Great Glen ran fifty or sixty miles straight northeast across the country in a line of lochs. A Scotsman standing nearby called out their names for us: Loch Lochy, Loch Oich, Loch Ness.

Keats, I remembered, had written a poem about his day on the mountain. I might try something in that line myself—but now the cloud closed in again. No view and no poem, at least for now. It was time to go down. I returned to town in cold rain.

Later, in London, I found Keats’s sonnet written “Upon the top of Nevis, blind in mist!” I would not try to compete with his fine iambs—even if he’d had still less of a view than I did.

Ambassador Bridges, thank you for sharing your thoughts about your trip to the very top of Ben Nevis. It must have been quite an experience by the sound of it. During the Keats Foundation Conference in 2018, there were many interesting and detailed papers on his Scottish Tour, covering many aspects of it, from the physical to the emotional one, as he felt guilty about leaving Tom behind. I think every poem is unique in and of itself, therefore, in case you do end up writing about your experience of climbing Ben Nevis, then I would be interested in reading it.

The sonnet on Ben Nevis is an example of philosophical, let alone literary, pessimism arising from Keats’s lack of formation and cultural ignorance. Keats is good at throwing around the word “mankind,” but always with an almost misanthropic gloom.

I think, with Keats, we really, really need to take him at his word when he describes himself as “a poor witless elf” in that most unfortunate of poems, one of the most notorious wasted opportunities in poetry.

Yes, it would be wonderful if you could give us something a little less glum and morose than the “witless elf” was able to chuck up.

I must take exception to the opinion of Mr. MacKenzie. I myself find Keats’s experiences during isolation of loved ones very relevant to those who are dealing with social distancing and enforced quarantine for some.

I am not a huge fan of Romanticism, but in my opinion, the idea that it has led to anything resembling a death of poetry is misinformed at best, and could even be called ludicrous. Poetry is not dead, nor was Keats a contributor to the sad state of modern poetry. (I would think that Whitman is much more responsible for the decline of traditional poetry and classical forms and styles).

I would also add that being thankful for anyone’s death—who wasn’t in mortal agony, beyond hope of healing—seems to me to be asocial, bordering on the misanthropic.

Mr Grein, thank you for your kind comments about the relevance of Keats’s experience of quarantine and suffering about 200 years ago. Most scholars consider the rise of Romanticism to be a watershed era in most fields, including poetry. For example the BARS association in the UK, and numerous others (including in the USA and Australia) have continued to study and publish papers and books on Romanticism: https://www.romanticism5000.com/romanticism-societies.html

https://romantic-circles.org/reference/links.html

Indeed, it’s a pity that poetry has declined so much in our times.

Your statement, Mr. Grein, seems to assume that social isolation is a miserable situation for everyone. Liberal misanthropes—who make up a good percentage of the “pooh widdle auld fowk” whom you are now exploiting in the name of virtue signalling—have been living quite contentedly in social isolation for years and years. Denying the existence of God and the human soul, surely they have no spiritual suffering. Those who raised their children to be authentic Christians are not in nursing homes to begin with.

In fact, cultural Marxism’s unweaving of society’s social fabric has been taking place for decades. We have been living in a socially disconnected world for a very long time, now. Haven’t you noticed how well the old liberals have taken to the “social distancing” charade, how well they have taken to wearing a communist diaper on their face—it would have been a Che or Malcom X t-shirt when they were young.

And even with arthritic hands, they relish the moment when they can whisk out their cell phones to snitch on neighbors who are not compliant with the isolationist edicts they themselves endorse.

In response to Mr. McKenzie,

Although my own worldview does not agree with the “panentheism” that characterized the worldview of many of the English Romantics, I nevertheless feel a sense of affinity with them because of the way they intuitively perceived through the beauty of the natural world around them, an eternal, spiritual realm that transcends the material and ephemeral world that presents itself to our physical senses. That´s why I have always found touching the works of Romanitic poets like .Wordsworth, whose Lines above Tintern Abbey made such a huge impact on me when I first read it as a teenager. I readily identified with that sense of awe Wordsworth felt when his contemplation of the world around him led him to feel “a presence that disturbs me with the joy of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime of something far more deeply interfused, whose dwelling is the light of setting suns, and the round ocean, and the living air, and the blue sky, and in the mind of man…” As a Christian, I believe that disturbing “presence” to be the living Creator of all, who is Himself the eternal Fountain of all beauty in the earth, the sea and the sky. So while I do not share the worldview of the Romantic poets, there are sentiments expressed in their writings– esp., that sense of an eternal reality that comes through contemplation of nature and beauty– with which my own heart resonates. These are the reasons that I cannot agree with your assessment that “Romanticism is the death of poetry.” How could anyone feel that Wordworth´s heartfelt response to daffodils “fluttering and dancing in the breeze” represents the death of poetry?

Mr Rizley, Thanks for your kind comments, specially, “I nevertheless feel a sense of affinity with them because of the way they intuitively perceived through the beauty of the natural world around them, an eternal, spiritual realm that transcends the material and ephemeral world that presents itself to our physical senses”. Indeed, that’s the case for millions of readers around the globe. It may interest you to know that in many Anglophone schools in India, for example, we had to read the major British poets, including Daffodils by Wordworth, and Tintern Abbey in the higher classes. I don’t know if this is still the case now, but a lot of Indians appreciate Romanticism because it resonates quite closely with our own aesthetics in our major languages. For example, many of the poems in Urdu by very well-known writers (such as Ghalib) have been set to music, and used as songs in Hindi films, so even the man on the street has been exposed to these poems which can be interpreted on a number of levels. Therefore, poetry has a special significance for many Indians, including Romantic poetry in English.

Sultana,

You seem to be saying that colonialism is not such a bad thing so long as the colonizers bring with them an element of high culture. It’s interesting to me how much of British culture has become a widely acknowledged element in Indian culture. Go Indians! My wife works in a Montessori school in Massachusetts, and some of her favorite parents are persons of Indian descent. For whatever reason, they are model Americans. Here in Massachusetts one Dr. Shiva is attempting to run against Elizabeth Warren for the Senate seat at stake. We wish him well.

Authentic Christians enjoy the Real Presence—the body, blood, soul, and divinity of Our Lord Jesus Christ— in the Most Blessed Sacrament, the Holy Eucharist.

Only pagans are reduced to conflating God’s presence with (a) mere creations, and (b) their inner selves.

“If crass creation by thine only bread,

“And thou thy self’s own king, tis, thou art dead.”

CONCLUSION

Keats will always be admired by sissies.

Christians enjoy the Real Presence—the body, blood, soul, and divinity of Our Lord Jesus Christ—in the Most Blessed Sacrament, the Holy Eucharist.

Only pagans are reduced to conflating God’s presence with (a) mere finite creatures, or (b) their inner selves.

“If crass creation by thine only bread,

“And thou thy self’s own king, tis, thou art dead.”

I actually agree with the statement in the line of poetry you quote. I think anyone who believes the teaching of John´s gospel has to agree that if a person´s only bread is earthly bread that perishes, and a person´s only king is proud self, then that is to be in a state of “death.” A Christian has Christ as his king and Christ´s flesh and blood as his spiritual food and drink. Where we would differ is in our understanding of how that “feeding on Christ” takes place in the Lord´s Supper. But to discuss that would involve a long theological conversation that is best pursued elsewhere than on a poetry website!

To C.B. Anderson, just to mention that the interest that Indians have in Anglophone culture is a positive side-effect of colonialism, but I hope I’m not implying that colonialism is to be condoned in any way. I wish these different cultures could have met more peacefully, and not necessarily after brutal wars. In fact, in England in the early 1800s certain sections of the intelligentsia were against colonial exploitation, which included Leigh Hunt, the editor of The Examiner, and his circle of young poets, such as Shelley, Keats and so on. As scholars are beginning to examine the political aspects of Keats’s poetry, they are finding more to chew upon. Here’s an example, with another one given in the comment to Mr Gosselin above:

[link no longer available]

Also, there’s been a big impact of Indian culture on the British artistic landscape as well, since it’s a two way street. I suppose there are too many books by British authors on/about/set in India to mention. Some of the early British writings about India are being looked at with a revisionist view now. While I appreciate E.M. Foster’s works, certain tropes in A Passage to India are being re-assessed by scholars. On the other hand, best-sellers such as The White Mughal by William Darymple continue to examine British presence in India, and their fascination with this country.

Thanks for your kind words about Indians. Since we have a huge population, there are bound to be all sorts of Indians, but I’m glad you met good human beings from India in your own town. Indians tend to have a different approach to parenting, and education is still regarded as being key to progressing in life, hence their keen interest in the schooling of their off-springs.

Yes, Sultana. I’m sincerely happy that you took the most positive aspects of my comment to heart. It’s my understanding that there are several poetry journals in India that are published in English. So far I’ve only had a poem published in one of them, TAJ MAHAL REVIEW. If I knew what other journals there were open to submissions in English, I’d get on it in an instant. In case you didn’t know this, it was some English official posted to India who first noticed that the names of numbers from one to ten in the Germanic languages had eerie correspondences with those same names as represented in Sanskrit. This was an important part of what led to comparative linguistics and the discovery that Sanskrit (> Hindi) are in the same broad language family. Whooda thunk it? Perhaps this has something to do with the mutual cultural fascination.

To C.B. Anderson, indeed, I think it would be much better if cultures could mingle instead of clashing in the beginning. Regarding Indian journals, I’m afraid I’ve been published mainly outside of India, as I left it a long time ago. I’m waiting for one of my poems to appear in an Indian journal now. However, in case you’re on Facebook, you’ll be able to find lots of calls for submissions, including from Indian journals. Here’s one: https://bengalurureview.com/page/submission-guidelines

Re: German and Sanskrit, it may interest you to know that there was/is a Goethe Institute in some major cities of India (where I learnt some basic German). Scholars are still exploring the connections between these languages, as they’re both from the Indo-European family. Perhaps less well-known is the connection between Sanskrit and Gaelic, which is slowly being explored as well. For instance, Spanish has many words of Arabic origin, as does Urdu, so it’s possible for some Urdu speakers to understand some Spanish words… I suppose the world has been more globalized for longer than we thought.

To C.B. Anderson, be careful what you wish for… I came across this list of literary journals published in India/by Indians. Since you were wondering about other Indian journals, here’s a list, though I haven’t tried them myself: https://thebombayreview.com/2020/06/19/top-literary-magazines-india-asia-creative-writing-publish-submit/

Bonne chance!

“Keats in the Time of Coronavirus” is the perfect title for an essay that poses so many questions surrounding our current situation and our own mortality. Death has never been more to the fore and your words capture that relationship with death many of us have at the moment.

In England, I grew up studying Keats and while admiring the wisdom of one so young, being (seemingly) so far away from the sharp scythe of the grim reaper, I never really appreciated how Keats’s relationship with death impacted his writing so greatly. I do now. Your essay has touched a raw nerve with me and makes me want to revisit every poem he wrote.

Thank you for your insightful eye and enlightening viewpoint.

Susan, these kind remarks coming from such a gifted poet, who has such a keen eye for detail, and can combine abstract thought so easily with elements from nature mean a lot to me. Indeed, researchers are still trying to fathom Keats’s deep musings on (im)mortality. Unfortunately, he’d had to think about it ever since the death of his father in childhood… Tolkien (who’s known as a late Romantic) seems to have the same obsession with (im)mortality due to losing his friends in WWII. Quite a few mature scholars have give moving talks on Keats after the demise of their loved ones at the Keats Foundation conferences in recent years. Perhaps our mortality can help us appreciate our time here, which I think your poems do so well.

MacKenzie’s stupidities give me an urge to indulge an ad hominem comment or two, but I long ago abandoned as futile any and all attempts at discourse, rational or irrational, with Flat Earthers and Christians.

Mr Brägg, thanks for your support. Though I can understand that people have different points of view, I appreciate your point about rational or irrational comments.

I’d like to mention that whereas this article (written during the lockdown) by Rob Crisell starts with ‘The Outstretched Hand’ by Keats,

https://www.theepochtimes.com/the-outstretched-hand-and-other-consolations-of-poetry_3352319.html

this speculative article ends with it:

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20190723-was-the-poet-john-keats-a-graverobber

Just to say I don’t agree with the writers on all points in the above article. Keats may have been fascinated with death, having been obliged to deal with it from a very young age, there’s been no evidence so far that he was a grave robber.

Here’s a short article about the Romantics and the pandemic:

https://k-saa.org/romanticists-in-lockdown-then-and-now/

And another short one that attempts to explain the fascination Indians have with the Romantics:

https://the-rambling.com/2020/01/23/issue7-sharma/

When alive, Keats was often blasted, as he was supposed to be a ‘Cockney’ poet, though this essay gives another reason why he was trashed in his lifetime. ‘This Living Hand’ is analysed starting from page 1010 of this rather long essay excerpted from a journal:

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/254511/pdf

Please feel free to share any other articles you come across about the Romantics and the current pandemic. It would be useful to create a list, all in one place.

Coming upon this article is a living fascinating experience for me, especially as a Nigerian poet. Permit me to say that I remain one of the admirers of Keats’s poetic artistries and explosions. My knowledge of Yoruba traditional raconteurs combined with the exhilarating Western Romanticism has been an interesting amalgamation in my own development.

Shola Balogun, am sorry, somehow I missed your comment on this essay. Thanks for your comment above. Am sure your own writing must be the richer because of your knowledge of another very different langauge. By the way, just to mention that ‘shola’ means flame in Hindi/Urdu. Am wondering if it means the same in your language too?

It is really awe-inspiring to know that ‘shola’ means ‘flame’ in Hindu/Urdu, Sultana Raza! My fathers are Sango worshippers. Sango is the Yoruba god of fire/flames. ‘Shola’, which is a short form of ‘Olushola/Olusola’- ‘Olu’ in Yoruba means ‘god’, while ‘Olushola/Olusola’ is ‘god has enabled me to acquire wealth’.

Shola Balogun, it’s funny how languages are inter-connected in ways that have not been fully explored. And also, how poetry and Keats enable people to connect from all over the world! Hope you acquire both literary (Keats’s ‘realms of gold)’ and more concrete gold too!

In case it’s interesting, here’s a more surreal essay, ‘Keatsian Mosaics 1817:2017,’ stitching Keats’s words with those of other artists and writers: https://impspired.com/2020/10/01/sultana-raza-2/

Sultana,

I greet you with all humility. The last time we spoke I was working on my collection of poems, The Dance is You, and, having the book out now, our last conversation comes to mind. I know your creative intelligent thoughts can see deeper into the depths of the book. I sincerely hope that I can get a copy across to you.

“There is no dance

When you are not in it.”

Thank you so much for your presence in this dance.

Blessings and more blessings to you always.

Shola Balogun, Author of The Dance is You

https://www.kobo.com/ww/en/ebook/the-dance-is-you

https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/1063207

https://okadabooks.com/book/about/the_dance_is_you/39845

The book of poems, The Dance is You, is available and readable in multiple ebook formats and devices.