The Director General of the WHO, Tedros Adhanom

His accent’s weird, his hair is pretty grey,

He is too calm to get into a fray.

His moustache bears the villainy of the WHO,

His pompous mouth suppressed the Wuhan flu.

He talked of “global solidarity,”

But buttressed China in reality.

Three years ago he was elected chief,

A crooked tale I shall relate in brief:

America and Canada did go

For British doctor David Nabarro,

While China’s Xi, just like a foul magician

Voila! produced this African politician,

To regulate the WHO at Xi’s command,

And give a speech that’s penned by Xi’s red hand.

Besides the Wuhan plague, Tedros concealed

Another plague of vast and deadly yield:

It was an Ethiopian cholera

He shrugged off as a political chimera;

For he is friends with China’s Communist Party

And therefore feels no need to say he’s sorry.

The New Millennium Report: June 2020

The worst are full of passionate intensity and hate.

The needless killing keeps occurring; it does not abate.

Dictators cross the globe with their police-state iron fists,

while rioters and looters justify their violence.

Crass anarchy and plagues are loosed upon our days and nights,

while people’s liberation armies trample human rights.

A Beast is rising from the blood-dim, ruddy, flooding tide.

O, who can fight against its might? O, who can break its stride?

Its worshippers give It authority, approve Its stay,

while dark clouds gather overhead. When will they go away?

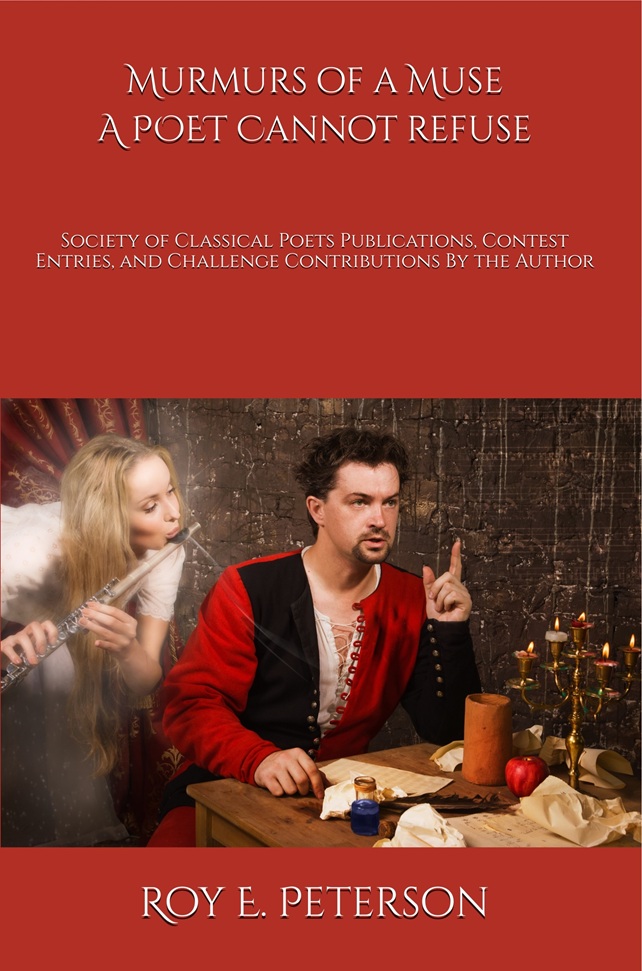

Notice, in the photo, how Adhanom’s knees are bent.

C. B., should one call that a genuflection or a curtsey? Either way, Sarban’s poem explains it well.

Margaret, we’re on the same page.

Although there are variants to the iambic pentameter launched in its opening lines, Mr. Bhattacharya’s “The Director General” is informative and succinct (20 lines).

And though it lacks the artistry of Milton, Marvell or Coleridge, it does attempt to interweave an interesting vocabulary. What I like is its World perspective, dropping people, places, opinions, and entities throughout its couplets.

As an aside, I find Mr. Bhattacharya’s readings of Milton, Marvell and Coleridge intriguing for his pronunciations, his cadences, and his energy.

Thank you, Mr. Wilbur Dee Case, for appreciating me. Yes, I used occasional variations to the iambic pentameter in order to maintain the general grammatical order of English words (or syntax), and to increase readability.

Moreover, you have accurately assumed my preferences. I am a great admirer of Milton, Marvell, Dryden, Pope and Coleridge. As a 22-year-old man, I still have a long way to go , and your unbiased criticism is always cordially welcome.

“The New Millennium Report: June 2020” obviously draws its essence from Yeats’ famous poem “The Second Coming”; though in no way does it approach either the originality or the creativity of Yeats. So what is Crise de Abu Wel up to?

The first thing one notes is the shortness of “The New Millennium Report”. It is a mere ten lines, a tennos, in fact. Words and phrases seem plucked haphazardly from “The Second Coming”; and to what purpose? L1 immediately lifts a clause, “the worst are full of passionate intensity” to which is added “and hate”. At this point it is fairly obvious that Crise de Abu Wel is applying Yeats’ words to the present time, which he paints as filled with hate and, as L2 points out, in its almost bland, but rather harsh, trochaic alliterative manner, “needless killing keeps occurring”.

The second couplet attends to dictators, rioters and looters with a unusual slant rhyme “iron fists and violence”, the very rhyme itself suggesting discord; while the third couplet turns Yeats’ “mere anarchy” into “crass anarchy” (echoic of Hardy), which along with plagues is “loosed upon our days and nights” along with the paradoxical “people’s liberation armies” trampling “human rights”.

The concluding couplets, reintroduce Yeats’ “Beast”, but without the Irish Modernist’s metaphorical power and striking imagery. Here one sees Yeats’ “blood-dimmed” shortened in the alliterative phrase”blood-dim, ruddy, flooding tide”. Crise de Abu Wel completes his poem in iambic hexameters with a question, perhaps echoing the hopelessness Yeats placed in “The Second Coming”; but unlike, the desert with its birds, Crise de Abu Wel has his Beast rising from a bloody sea with dark clouds overhead. It is both the differences and the similarities between the two times and ways of looking at them that Crise de Abu Wel marks in his lines. Even the shortening itself makes the tennos seem almost telegraphic.