.

The Whiskey Priest

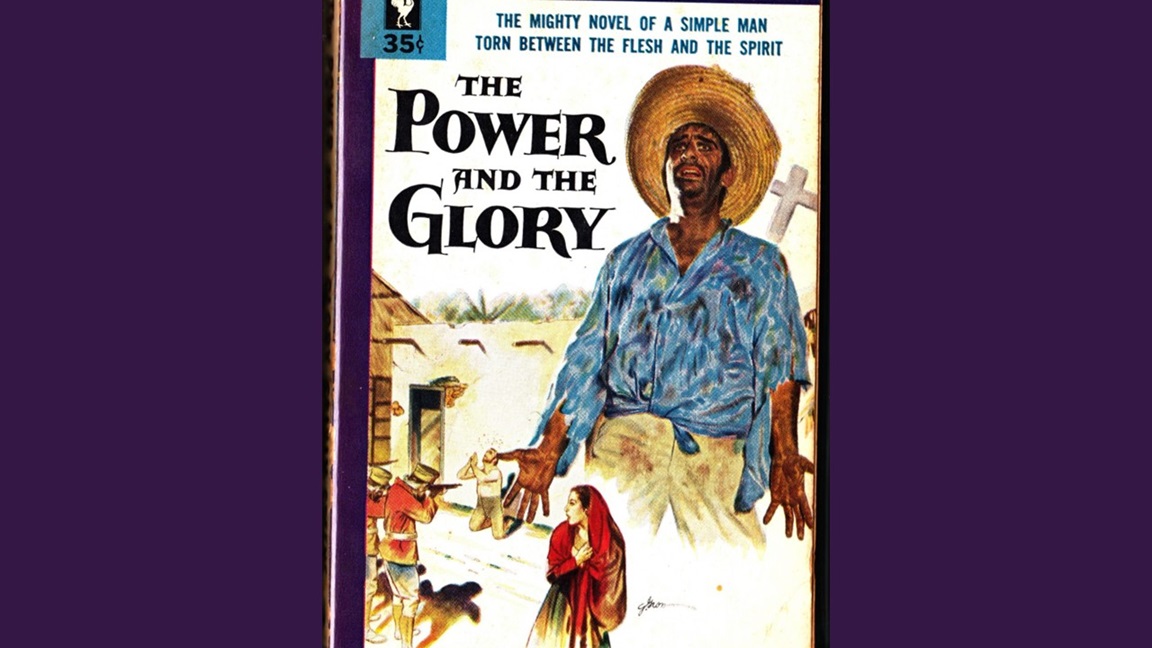

based on The Power and the Glory by Graham Greene

I stand condemned because I am a priest,

Condemned to die by law here in Tabasco,

The last eight years of memories I’ve pieced

Together show my life’s one big fiasco,

For, stupidly, when all priests fled oppression,

I stayed down in Tabasco for prestige,

So now there’s no one who can take confession

Or chase the devils who my soul besiege.

Oh, why did I assume that I could stay

When others had the sense to move away?

I cheated on the Church with young María,

A woman who could never be my wife—

No need to search God’s Word like at Berea

To know we stole His fire for making life!

I can’t repent of having made my daughter;

For love of her, I’m headed straight to Hell.

This morning, like a lamb, I face the slaughter—

I’d have more courage if with Christ I’d dwell!

And yet, had I that moment to redo,

For her, I’d sacrifice my soul anew.

I’m damned, for, like a sheep, I’ve gone astray.

My thoughts turn to my daughter; she’ll be seven

And reach the age of reason. God, I pray,

Please help her gain eternity in Heaven!

I weep, because I’m Father to all laymen,

But favor she who’s made from half my genes

With all my love and wish to save—such shame in

Being a priest, ignoring what it means!

As Jacob favored Joseph among his sons,

My heart toward no one but my daughter runs.

I risked my life—for what? The rare Communion,

A few confessions for the village folk.

If I am damned for my illicit union,

Dear Lord, let them be spared the devil’s yoke!

I’m only here because someone requested

I take confession from a dying man,

And quickly turned me in to be arrested

As all along had been his Judas plan!

Perhaps it’s best that such a worm as I

Be sent to prison, all alone to die.

I grab and chug another flask of brandy

With guilt of all the deadly sins received.

I could be richer than a Spanish Grandee

If I had just denied that I believed!

I’d have María and a hefty pension,

My daughter, sons as newest plants in youth,

If I had just succumbed to the pretension

And turned my back forever on the Truth!

My sin annuls the fact that all those days,

For God’s Most Holy Word, I’ve kept hard ways.

I turned a home and family down for nada.

I turned away from God by one grave sin.

I’ve neither now. His angel-saint armada

With flashing, flaming swords won’t let me in,

And as I fly to Jesus, He’ll deny me.

I’ll fall like lightning to the Lake of Fire.

Even the Blessed Virgin won’t stand by me;

I chose to burn in Hell for my desire.

So, chastity is nothing to disparage;

Don’t be like me! Save all those things for marriage.

It soon shall be as if I’d not existed.

I’ll meet God empty-handed, nothing done.

In Heaven’s book, my name will be unlisted.

I’m useless, barely ever helped a one.

Confessions few, an endless bad example,

Ignoble death—this legacy I leave.

Eight years to serve my fellow man was ample—

How easy sanctity was to achieve!

In doing good I had too much restraint,

Yet all that counted was to be a saint.

.

“Whiskey priest:” A term coined by Graham Greene for his novel,

describing a priest who, like the protagonist, shows moral weakness

but still believes in a higher standard and shows courage.

“Tabasco:” A province of Mexico, west of the Yucatán Peninsula and

bordering the Gulf of Mexico. The region was taken over by Radical

Socialists in the 1930s, when the novel takes place. Priests were

given wives and pensions in exchange for renouncing their faith and

all priestly functions, and refusing was a capital crime.

“Cheated on the Church:” Catholic priests enter into a marriage-like

covenant with the Catholic Church and hence are said to be married to

the Church.

“Berea:” Acts 17:11

“Like a lamb,” etc.: Isaiah 53:7

“Like a sheep,” etc.: Psalm 118 (119):176, cf. Isaiah 53:6

“Sons as,” etc.: Psalm 143 (144):12

“Kept hard ways:” Psalm 16 (17):4

“Lake of Fire:” Revelation 19:20

“Blessed Virgin:” The Virgin Mary, the mother of Jesus. Catholics have always believed that in Heaven, she prays for sinners, especially the hard cases.

.

.

Joshua C. Frank works in the field of statistics and lives in the American Heartland. His poetry has also been published in Snakeskin, The Lyric, Sparks of Calliope, Westward Quarterly, New English Review, and many others, and his short fiction has been published in several journals as well.

Joshua, what an amazing insight into the socialist/communist workings in Mexico to control religion. As you know, in the Soviet Union, Lenin persecuted the church and those who went to cathedrals, because of Marxian atheism. This lasted in hard core form until WWII when Stalin decided rather than engage is full-scale persecution, it made sense to use the Russian Orthodox church with its reach extending to the whole world of Christianity in order to further communism. Control measures included recruiting some of the priesthood to the KGB for reporting purposes, using the cathedrals as atheist propaganda centers, taking the names and addresses through the already mandated internal passports, requiring the priests and bishops to sign papers stating that they did not truly believe in God, and encouraging them to have mistresses, among other things. As an Army Attache, I witnessed in one city a cathedral used as an atheist propaganda center with anti-religious banners and trappings. When my wife and children decided to go to a Moscow cathedral for Easter, they encountered a police barricade with check points where they had to show their passports as their attendance was recorded. Your poem is a great depiction that surely has been repeated throughout the communist/socialist controlled countries with China as one of the greatest continuing persecutors.

The Globalists, the One Worlders, the Mega-Corporations, the Woke Left, and the Environmentalists long ago decided that an organized religion of world-wide scope was the best way to control mass populations.

The attempt to control and corrupt the Catholic Church has always been a cherished goal of these groups, and their predecessors as far back as the Freemasons.

How far they have succeeded in this scheme can be measured simply by looking at the current Anti-pope living in Casa Santa Marta, and what he has managed to do in a mere decade.

I don’t know whether he’s an antipope or not, but either way is just as scary as the other.

Michael Bunker wrote in his book Surviving Off Off-Grid that modern “Christianity” is merely the religious arm of the modern, industrialized world. More and more, I find myself agreeing with that.

Thank you, Roy. That’s some very interesting history.

I’ve read that Polish Christians kept their faith under Communism and then lost it under our modern capitalist system. Gulags couldn’t kill their faith; it took television and shopping malls open on Sundays.

Communism was merely the seed of what we have today.

Josh, this is a wonderful, ambitious and meaningful dramatic monologue in the voice of a greatly challenged literary character. Is this character based on a historical figure? If not, it is clear that he represents an entire class of priests abused by the atheist Mexican government of the 20s and 30s in the course and wake of the Cristero War.

You admirably tell a tale of faith wounded, of betrayal, of the competing pulls of family and God. To successfully integrate so many elements and themes into one piece is big poetic achievement. I especially like your use of form — a rather long poem of 70 lines n which each 10 line stanza or a-b-a-b-c-d-c-d-e-e- is like a shortened sonnet. This is a good story-telling choice because, with that ending couplet, actually conveys the sense of a chapter completed.

Most important of all, in my view, is that you have made the reader care about this speaker and his plight. A beating, troubled heart shines through and one is inspired to pray for this man — and for all those who are betrayed for their faith and torn between the material and the spiritual. These are very contemporary issues as the faithful in contemporary times find ourselves under not dissimilar attack.

Thank you, Brian! That’s such a compliment. I’m honored. Also, as usual, you’ve hit upon the point of the poem.

To answer your question, when Greene took a trip to Mexico, he heard people talk about a “whiskey priest” who went around giving people the Sacraments; the novel was based on their stories.

When I read the novel, I was particularly struck by two things: 1) How he kept going on despite being certain that he was damned, and 2) how, once he had brought his beloved daughter into existence through sin, he couldn’t bring himself to regret having done so. These two ideas are what inspired the poem.

Joshua, Of course there is a subjective element to literary interpretation, but I always thought that the Whiskey Priest’s final revelation about being a Saint was a redemptive one – that he finally realized Sainthood was about recognizing one’s own sinfulness and falling on the grace of Christ. It seems like Greene cements this with the symbolic arrival of a new priest in the last chapter, showing that someone else is picking up the torch that the Whiskey Priest, who carried it very imperfectly, can no longer carry. At any rate, I don’t think that “The Power and the Glory” ends on a despairing note, as many of Greene’s works do.

Sorry, “Joseph”! (people accidentally call me “Jonathan” all the time).

Thank you, Jeremiah. That’s an interesting idea. I always assumed the Whiskey Priest was mostly in despair but had one last note of hope that God might have mercy on him.

Josh, much has already been said about “The Whiskey Priest” in the rich array of comments above. I would just like to add that the pain of the narrator is palpable adding weight to the heartbreaking tale. I thoroughly enjoyed Graham Greene’s ‘Brighton Rock and now (decades later) ‘The Power and the Glory’ has piqued my interest, such is the pull of your poem. Thank you!

Thank you, Susan! It’s great to hear that my poem has gotten you interested in the novel on which it was based, and that I was able to convey the speaker’s pain so well.

Joshua, this is a splendid verse monologue of complicated psychology. The speaker may be overscrupulous and is definitely in despair. He speaks clearly enough to credit him with sanity; he’s not entirely overwhelmed by alcoholism, although that must have an effect on his thinking. But then, so does the isolation from the brotherhood of the priesthood–and the apparent fact that Tabasco people are not the kind of faithful who would support a priest from whom they could benefit. Even Maria seems to have disappeared, leaving the daughter as the priest’s only person to love. He remembers he should still be a father to all the laity, but one Judas has betrayed him, and since it was that man’s intent to trap the priest on behalf of the oppressive government, the confession he may have made would have been a farce that did no one any good.

We can see the whiskey priest’s unrepented sin of preferring his daughter even to God, and of despair in refusing to call on Jesus and Mary. He also devalues the good he may have done in the few sacraments he administered in eight years. Yet in the three lines of regret at the very end of the poem, where he says he had too much restraint in doing good, we see the beginnings of a vision of himself as an effective underground priest. Seems to be sorry he didn’t try it, although he’s surely not correct to say it would have been easy! You leave the stark scene without supplying an omniscient author ending (true contrition or not), which seems best for consistency.

Colonel Peterson has rightly remarked on the situation as one of communist and socialist tactics, and I will add pensions were employed in the 16th century by Henry VIII of England to enforce his dissolution of religious life. It was a gradual process, starting with smaller houses and going on to larger ones, with very few refusals of the money by English men or women living under solemn or simple vows. Their option was self-imposed exile to the continent, or martyrdom. Most priests were left in place to serve the new religion, as Joseph Salemi has indicated, though the English pensions pre-date organized freemasonry.

Thank you, Margaret. I appreciate your analysis, as well as that bit of English history.

The omniscient author ending wasn’t in the book, either. I felt it best to write the speaker’s thoughts just before the end of the story.

I first found out about the novel from this editorial in Crisis Magazine, which gives another detailed analysis: https://crisismagazine.com/opinion/imitating-the-saints-from-don-quixote-to-the-whiskey-priest

This is really excellent writing, Joshua. It makes me want to go back and read the novel again, especially since I’m sure that when I read it so long ago, I didn’t grasp every aspect of it that you’ve expounded upon here. Thank you for this profound poem.

Thank you so much, Cynthia. I’m honored that you consider it really excellent writing, and I’m glad the poem is sparking interest in the original novel.