By Dusty Grein and Evan Mantyk

“The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe remains one of the English language’s most popular and influential poems since it was written in 1845. Much of this was Poe’s own doing, as he performed it quite frequently, and wrote many essays and commentaries on it in the press. It has cemented itself in the modern era, and has been the subject of many portrayals, from Vincent Price in the 1960s to the Simpson’s rendition in the 1990s.

One of the keys to its incredible appeal is its brilliant rhyme pattern and rhythm. While the language may be somewhat difficult to understand or relate to, people keep returning to it for Poe’s enchanting classical meter.

We are going to explore this poem’s rhythmic genius in depth, give some examples of other poems that “Raven” fans might like, take a look at the poem itself, and discuss using this poetic framework to build a poem of our own.

Poems Similar to “The Raven”

Many people list “The Raven” as their favorite poem, and their interest in poetry ends there. They hear or read some free verse, which lacks clear rhyming or rhythm, and sadly for some, the attraction to poetry is over.

If you like “The Raven,” but don’t really care for free verse poetry, don’t lose hope! There are many other poems that have similar classical meter. In particular, the following poems have a rhythm very similar to that of “The Raven”:

Recent Poetry

A Reincarnation of the Raven

The Anchor

The Drunken (A Parody of the Raven)

Ode to a Soldier’s Wife

Older Poetry

Song of Hiawatha by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

The Bells by Edgar Allan Poe

Tyger, Tyger by William Blake

The Poem

In an early draft of the poem, Poe actually had a parrot instead of a raven. This gives us some basic idea of what is going on throughout this poem. A man is sitting in his study late at night when he hears knocking. He opens the door, but no one is there. After more knocking, he opens the window and a Raven flies in, seeking shelter from the stormy night. It then begins repeating the same word over and over again: “nevermore.”

In an otherwise realistic poem, this slight supernatural flourish creates just the right amount of mystery to push the story along as we learn about the narrator’s lost love, Lenore, who will return “nevermore.” The bird’s echoed mutterings to the questions he asks make him feel even worse in his melancholy.

Not exactly a brilliant plot filled with divine insight, but a study in deep emotion and a vehicle for vigorous language. It poignantly and beautifully depicts the haunting feeling of longing one has for a love which is distant or lost.

Here is his masterpiece in its beautiful entirety, as reprinted in the Richmond Weekly Examiner, September 25, 1849 (by permission of Poe himself):

Useful vocabulary when reading the poem:

–Pallas: Another name for Athena, Greek goddess of wisdom and war

-Plutonian: Derived from Pluto: Another name for Hades, which refers to both the Kingdom of the Dead and the god of the Dead.

-Seraphim: six-winged angel

-Nepenthe: an ancient medicine for relieving sorrow originating from Egypt

-Balm in Gilead: a rare medicinal perfume mentioned in the Bible that has come to represent a cure-all

-Aidenn: The Garden of Eden ; paradise in a general sense

{This version is a direct reprint, retaining the original spelling, approved by Poe himself}

THE RAVEN.

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore —

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

“ ’Tis some visiter,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door —

Only this and nothing more.”

Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December;

And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor.

Eagerly I wished the morrow; — vainly I had sought to borrow

From my books surcease of sorrow — sorrow for the lost Lenore —

For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore —

Nameless here for evermore.

And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain

Thrilled me — filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before;

So that now, to still the beating of my heart, I stood repeating

“ ’Tis some visiter entreating entrance at my chamber door —

Some late visiter entreating entrance at my chamber door; —

This it is and nothing more.”

Presently my soul grew stronger; hesitating then no longer,

“Sir,” said I, “or Madam, truly your forgiveness I implore;

But the fact is I was napping, and so gently you came rapping,

And so faintly you came tapping, tapping at my chamber door,

That I scarce was sure I heard you” — here I opened wide the door; ——

Darkness there and nothing more.

Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering, fearing,

Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before;

But the silence was unbroken, and the stillness gave no token,

And the only word there spoken was the whispered word, “Lenore?”

This I whispered, and an echo murmured back the word, “Lenore!” —

Merely this and nothing more.

Back into the chamber turning, all my soul within me burning,

Soon again I heard a tapping somewhat louder than before.

“Surely,” said I, “surely that is something at my window lattice;

Let me see, then, what thereat is, and this mystery explore —

Let my heart be still a moment and this mystery explore;—

‘Tis the wind and nothing more!”

Open here I flung the shutter, when, with many a flirt and flutter,

In there stepped a stately Raven of the saintly days of yore;

Not the least obeisance made he; not a minute stopped or stayed he;

But, with mien of lord or lady, perched above my chamber door —

Perched upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door —

Perched, and sat, and nothing more.

Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling,

By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore,

“Though thy crest be shorn and shaven, thou,” I said, “art sure no craven,

Ghastly grim and ancient Raven wandering from the Nightly shore —

Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night’s Plutonian shore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

Much I marvelled this ungainly fowl to hear discourse so plainly,

Though its answer little meaning — little relevancy bore;

For we cannot help agreeing that no living human being

Ever yet was blessed with seeing bird above his chamber door —

Bird or beast upon the sculptured bust above his chamber door,

With such name as “Nevermore.”

But the Raven, sitting lonely on the placid bust, spoke only

That one word, as if his soul in that one word he did outpour.

Nothing farther then he uttered — not a feather then he fluttered —

Till I scarcely more than muttered “Other friends have flown before —

On the morrow he will leave me, as my Hopes have flown before.”

Then the bird said “Nevermore.”

Startled at the stillness broken by reply so aptly spoken,

“Doubtless,” said I, “what it utters is its only stock and store

Caught from some unhappy master whom unmerciful Disaster

Followed fast and followed faster till his songs one burden bore —

Till the dirges of his Hope that melancholy burden bore

Of ‘Never — nevermore’.”

But the Raven still beguiling my sad fancy into smiling,

Straight I wheeled a cushioned seat in front of bird, and bust and door;

Then, upon the velvet sinking, I betook myself to linking

Fancy unto fancy, thinking what this ominous bird of yore —

What this grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt, and ominous bird of yore

Meant in croaking “Nevermore.”

This I sat engaged in guessing, but no syllable expressing

To the fowl whose fiery eyes now burned into my bosom’s core;

This and more I sat divining, with my head at ease reclining

On the cushion’s velvet lining that the lamp-light gloated o’er,

But whose velvet-violet lining with the lamp-light gloating o’er,

She shall press, ah, nevermore!

Then, methought, the air grew denser, perfumed from an unseen censer

Swung by seraphim whose foot-falls tinkled on the tufted floor.

“Wretch,” I cried, “thy God hath lent thee — by these angels he hath sent thee

Respite — respite and nepenthe, from thy memories of Lenore;

Quaff, oh quaff this kind nepenthe and forget this lost Lenore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

“Prophet!” said I, “thing of evil! — prophet still, if bird or devil! —

Whether Tempter sent, or whether tempest tossed thee here ashore,

Desolate yet all undaunted, on this desert land enchanted —

On this home by Horror haunted — tell me truly, I implore —

Is there — is there balm in Gilead? — tell me — tell me, I implore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

“Prophet!” said I, “thing of evil! — prophet still, if bird or devil!

By that Heaven that bends above us — by that God we both adore —

Tell this soul with sorrow laden if, within the distant Aidenn,

It shall clasp a sainted maiden whom the angels name Lenore —

Clasp a rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore.”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

“Be that word our sign of parting, bird or fiend!” I shrieked, upstarting —

“Get thee back into the tempest and the Night’s Plutonian shore!

Leave no black plume as a token of that lie thy soul hath spoken!

Leave my loneliness unbroken! — quit the bust above my door!

Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door;

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon’s that is dreaming,

And the lamp-light o’er him streaming throws his shadow on the floor;

And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor

Shall be lifted — nevermore!

Deciphering The Raven’s Meter

Quick review from “Basics of Classical Poetry”: a trochee is a two-syllable foot, comprised of a hard syllable followed by a soft one—the opposite of an iamb—and trochaic lines are built from these trochees. A tetrameter is a set of four poetic feet, and an octameter is eight poetic feet.

Poe was a skilled craftsman of the English language. His mastery of difficult poetry is evident here in the use of trochaic octameter. He himself published an essay, “The Philosophy of Composition,” regarding the methodical process he used to create his poem. In it, he explains, step-by-step, how “The Raven” came to be, and the logic behind each image and emotion.

Instead of focusing on these creative decisions and the philosophy that is expressed through the process, I would like to discuss the mechanics behind the poetic architecture of the piece. It is the one area that Poe only lightly touches on, and this structure—if followed closely—will help the aspiring poet to build a narrative poem, based on whatever subject he or she desires, with a melodic cadence and flow.

The poem itself was created in trochaic syllable pairs, instead of iambic ones, and each stanza is comprised of eleven tetrameters. These are welded together into five octameter lines, followed by the final refrain-like tetrameter line, the Raven’s immortal quote and that ominous long “OR” sound.

He also used the subtle trick of omitting the final syllable on lines two, four, five and six, which all rhyme. This method is called catalectic (headless), and emphasizes these lines by letting the final syllable stand alone.

Finally, the poem was built using a very strict rhyming pattern as follows:

AA,

xB,

CC,

CB,

xB,

B

Adding to the difficulty of this masterpiece, is the fact that the same refrain rhyme syllable (the B in the pattern) is used in all eighteen stanzas of the poem.

To clarify, let’s look at the structure of the poem (x means that no rhyme is needed):

[A A] Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

[x B] Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore —

[C C] While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

[C B] As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

[x B] “‘Tis some visiter,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door —

[B] Only this and nothing more.”

If you read just the italicized words—the fourth trochee in each tetrametered half-line—you will see the inherent flow of the piece.

Creating a Poem, Following This Pattern

Building a poem on this frame presents us with some challenges. First let’s break down the number of rhyming words:

“A” words – We need at least two of these rhyming words, that must end with a trochee (two syllables, with the first one stressed). I myself like the challenge of finding three of these words that rhyme, and using the third one in line #2, in place of the “x” word, treating it like the “C” words in lines #3 and #4.

“C” words – We need three of these. Like the “A” words, these three rhyming words must end in a trochee, and are easiest to do with two syllable words.

“B” words – Here is the true challenge. We need four rhyming words, of a single stressed syllable. These will replace the eighth trochee at the end of lines #2, #4, #5 and the fourth at the end of line #6.

“x” words – Here for use in line #5 (and #2 if you desire) is our connecting trochee, as the fourth of eight in the line. This trochee does not have to rhyme, although I like to make the one in line #2 an “A” rhyme. Poe sometimes does this, and other times does not.

An Example

This style of poem lends itself quite well to stories that are supernatural or terrifying, although it could express emotions in any genre. For the purposes of this exercise, I will create an example using fear to create a mood.

I once saw an image of several bodies floating in the air above an old weed-covered yard, and it is the image I will convey through the example stanza.

Following Poe’s framework, I will use 3 “A” words, 3”C” words, and 4”B” words. I will use a single “x” tie in trochee for line #5.

Here then are the words I selected, chosen for rhyme, and mood:

3 “A” words – wander, ponder, yonder *(Note that these are all trochees)

3 “C” words – tighten, whiten, frighten(ed) *(Again, all trochees)

4 “B” words – see, flee, free, me *(These are all single hard syllables)

Using the pattern, we will now write out the framework of our piece, using | for the hard syllables, and—for the soft ones with each trochee, and inserting our selected words:

| – | – | – wander | – | – | – ponder ____(total syllables: 16)

| – | – | – yonder | – | – | – see _______(total syllables: 15)

| – | – | – tighten | – | – | – whiten _____(total syllables: 16)

| – | – | – frightened | – | – | – flee _____(total syllables: 15)

| – | – | – | – | – | – | – free __________(total syllables: 15)

| – | – | – me___________________(total syllables: 7)

The Result

Here is where creativity and imagination as a poet truly express themselves. Keeping the meter in mind, we build the lines, by inserting three trochees in front of each previously selected word, and a single tie-in trochee in line #5.

Here is a stanza I created, built onto this framework:

Cautiously at night I wander through the moonlight, there to ponder

On the shapes that hang but yonder, at the edge of what I see.

Fearfully my muscles tighten and my face begins to whiten;

Though I try not to be frightened, ’tis a battle not to flee.

In the darkness something flutters, struggling, trying to get free –

In the dark, calling to me.

There you go. The creation of a single stanza of a narrative poem, written in structured catalectic trochaic octameter. Sounds a lot more complicated than it really is. Edgar Allen wrote his epic poem using 18 stanzas, 108 lines, to tell the story of “The Raven”— but then he was a true master.

A 52 year old grandfather, Dusty has just recently become a professional author. He lives in Newberg, Oregon, where a dog named Naked, and his youngest daughter Jazzmyn keep him busy.

Evan Mantyk teaches literature and history in the Hudson Valley region of New York.

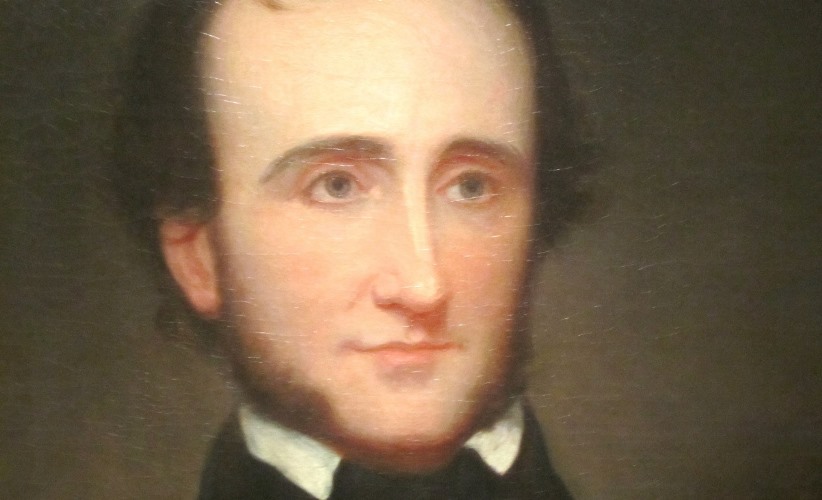

Featured Image: A portrait of Poe done by Samuel Stillman Osgood (1808-1885) right around the time that “The Raven” was written.

i think poe’s genius is “realness” in his time. as time degrades, “realness” based on that time becomes less and less genius. his time was still traditional. our time is not. so our honesty factors are based on bygone mores. in some way perhaps. i suppose that makes genius a fiction. it’s all about character. real things never change.

I find this article extremely helpful

The roll and the rhythm is the mark of a true master that we can but mimic, indeed!

I had to write a poem that imitated Poe’s “The Raven” for English class, and this really helped!

Thanks 🙂

I had to write a poem like Poe’s for English summer school. I thought it would be hard but it was a lot easier. This site really helped.

I am making this my 2017 End and 2018 Challenge.

A Tribute to Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven”

Penned by a Trinidadian – Narendra Rajkumar – 22.12.17

The Parakeet – our miniature Parrot

1 Stanza only.

Soaring so high, the Eagles are single, they are unable to mingle,

Rainbow coloured morning shadowed the anxious way I feel.

Rain droplets and whistling birds wanting to know where I was staying,

Pita Patter musical sounds were playing their notes so real.

Green parrots and parakeets garnered fruits and seeds for their meal –

Let us protect each bird.

First Serial Rights / Narendra Rajkumar.

I have a great deal of evidence proving that Poe didn’t write “The Raven.” It was written by Mathew Franklin Whittier, younger brother of poet John Greenleaf Whittier, after the death of his first wife, Abby. MFW submitted it to the second issue of “American Review” when he was living in New York City and writing for the NY “Tribune.” He was a long-time admirer of poet Francis Quarles, which is why he signed the poem “—- Quarles.” This just scratches the surface of my evidence.

I had to write a poem in English class and my teacher said I had to do a poem that had the same rhythm and everything as Edgar Allen Poe’s poem “The Raven.” I tried to make my own, but I couldn’t so when I found this site, I knew how to make a poem sound like Poe’s. Thank you very much for a site like this for giving me 100/100