[column size=one_half position=first ]

Translation

(1)

By a hedge, the day before,

I met a half-breed shepherdess

Full of cheer and sense no less—

A peasant woman’s child. She wore

A cloak of fur. One could adore

Her simple skirt and canvas clothes,

Wooden clogs and woolen hose.

(2)

I crossed the field to say hello.

“Girl,” I said, “you fetching thing, you—

I fear the wind will chill and sting you.”

The girl said “Sir, it is not so.

God and my nurse have made me grow,

And whether winds blow strong or stealthy,

I stay happy, safe, and healthy.”

(3)

“Girl,” I said, “sweet pious child,

I have detoured from my way

To keep you company this day.

I reckon it a thing ill-styled

That in this place, remote and wild,

You tend so big a flock as this

All alone, companionless.”

(4)

“My lord,” she said, “whatever I be,

Folly and sense I can discern.

Your company, good sir, I spurn

And leave it to your lady. She

Has more right to the thing than me—

Your luckless lady who believed

She had it, but is quite deceived.”

(5)

“Girl of noble stance and gait,

That father was a cavalier

Who sired you—your mother dear

Though low-born seemed of high estate.

The more I gaze on you I rate

Your beauty higher, and I brighten.

Can you not unbend, untighten?”

(6)

“Sir, my conduct and my race

Are rooted and go, as I avow,

Back to the pruning knife and plow—

That is the heritage I trace.

But there are knights whose better place

Would be to work till their bones creak

For six days out of every week!”

(7)

“Girl,” I said, “a fairy queen

Gave you a polished gift at birth—

A loveliness of priceless worth

Beyond all peasant girls I’ve seen.

Such beauty would have twice its sheen

If I could see myself above

Just once, with you below, in love.”

(8)

“Good sir, you’ve heaped on me such praise

And lifted me so high in price

It pleases me—but take advice:

In payment for such pretty lays

May you, as you go your ways,

Take this farewell: ‘Gape, buffoon!’

While you stand dumbstruck at noon.”

(9)

“Girl, all savage wicked hearts

Can be tamed by cultivation.

I know, from long-drawn expectation,

A peasant girl of your sort starts

To soften in her sternest parts

And makes a man fine company

When neither lies—not he, not she.”

(10)

“Lord, when men are folly-driven

They make you promises and vows.

Sir, your homage disallows

My maidenhood, the which I’ve striven

To keep. I shall not be forgiven

If I sell cheap my unplucked fruit

And change my name to prostitute!”

(11)

“Girl, it’s so that every creature

(Let us speak in language pure)

Is true to type, and to be sure,

Reverts at last to innate feature

Since nature is the final teacher.

In a small shed by this field

You’ll feel safe, and sweetly yield.”

(12)

“Yes, my lord, but think what’s right—

A fool seeks folly as a sport.

A courtly man seeks dames at court,

A peasant seeks his own delight.

And many places suffer blight

Because folks have ignored degree—

So say the wise old folks to me.”

(13)

“Lovely one, I have not seen

Another, of your shape, so vicious

Nor with a cruel heart so capricious.”

(14)

“My lord, the owl lets us know

That one man gazes at a painting—

Another longs for manna, fainting.”

[/column]Original Provençal

(1)

L’autrier just’una sebissa

Trobey pastora mestissa

De joi e de sen massissa,

E fon filha de vilaina;

Cap’e gonela, pelissa,

Vest e camiza treslissa,

Sotlars e causas de laina.

(2)

Ves lieys vau per la planissa;

“Toza,” fi m’ieu, “re faytissa,

Dol ay gran del ven que.us fissa.”

“Senher,” so dis la vilayna,

“Merce Dieu e ma noirissa,

Pauc m’o pres si.l vens m’erissa,

C’alegreta soi e sayna.”

(3)

“Toza,” fi m’ieu, “cauza pia,

Destoutz me soy de la via

Per far a vos companhia,

Car aytal toza vilayna

Non pot ses parelh paria

Pastorjar tanta bestia

En aytal loc, tan soldayna.”

(4)

“Don,” fay sela, “qui que sia,

Ben conosc sen o fulia;

La vostra parelhayria,

Senher,” so dis la vilaina,

“Lay on se tanh si s’estia,

Que tals la cuj’en baylia

Tener, no n’a mays l’ufayna.”

(5)

“Toza de gentil afayre,

Cavayers fo vostre payre

Que.us engenret, e la mayre

Tan fon corteza vilayna.

Com pus vos gart, m’es belayre,

E pel vostre joi m’esclaire;

Si fossetz un pauc humayna!”

(6)

“Senher, mon genh e mon ayre

Vey revertir et retrayre

Al vezoich et a l’arayre,

Senher,” so ditz la vilayna;

“Mays tal se fay cavalgayre

C’atretal deuria fayre

Lo seis jorns de la semayna!”

(7)

“Toza,” fi m’ieu, “gentil fada

Vos adrastec can fos nada

D’una beutat esmerada

Sobre tot’autra vilayna;

E seria.us be doblada,

Si.m vezi’una vegada

Sobiran e vos sotraina.”

(8)

“Senher, tan m’avetz lauzada

Pus en pretz m’avetz levada,

Qu’ar vostr’amor tan m’agrada,

Senher,” so dis la vilayna,

“Per tal n’auret per soldada

Al partir, ‘Bada, fol, bada!’

E la muz’a meliayna.”

(9)

“Toza, fel cor e salvatje

Adomesg’om per uzatge;

Ben conosc al trespassatje

C’ap aital toza vilayna

Pot om far ric companatje

Ab amistat de coratje,

Can l’us l’autre non enjaina.”

(10)

“Don, hom cochat de folatje

E.us promet e.us plevisc gatje;

Si.m fariatz omanatge

Senher,” so dis la vilayna,

“Mays ges per un pauc d’intraje

Non vuelh mon despieuselatje

Camjar per nom de putaina!”

(11)

“Toza, tota criatura

Revert segon sa natura.

Parlem ab paraula pura,”

Fi m’ieu, “tozeta vilayna.

A l’abric lonc la pastura,

Que mels n’estaretz segura

Per far la cauza dossayna.”

(12)

“Don, oc—mas segon drechura

Serca fol sa folatura,

Cortes cortez’aventura.

E.l vilas ab la vilayna;

“E mans locs fay sofraytura

Que no.y esgardo mezura,

So dis la gens ansiayna.”

(13)

“Bela, de vostra figura

Non vi autra pus tafura

Ni de son cor pus trefayna.”

(14)

“Don, lo cavecs nos aüra

Que tals bad’en la penchura

C’autre n’espera la mayna.”

Afterword

L’autrier just’una sebissa is a very early example of the pastourelle or debate-poem involving a knight and a shepherdess. It is by one of the first-known troubadours, Marcabru of Gascony. He may have been the one to initiate the genre, which goes on to have a long life in European literature.

The poem is in fourteen strophes of octosyllabic lines, with a rhyme scheme of AAABAAB. The concluding two strophes are of three lines each, rhyming AAB. In this English version I have kept the length of every strophe, employing a four-stress meter to approximate the original Provençal. But for ease of translation I have used the more manageable rhyme scheme of ABBAACC in the seven-line strophes.

The narrative gist of this pastourelle is simple enough. The poem begins with a nobleman (probably a young knight) seeing a shepherdess in a field with her flock. She is a “half-breed” (mestissa), the illegitimate offspring of a nobleman and a peasant woman. The knight accosts her to make some small talk, saying that he is concerned with her being cold and alone.

She assures him that she is quite alright—safe, healthy, and in no need of protection. When he replies that he has come to give her his “company” (companhia, a word with amorous overtones), she fires back saying that she is not stupid, and that his “company” belongs to his wife, not to her. The shepherdess’s words make it clear that she is well aware of the knight’s dishonorable intentions.

The knight then attempts to lessen their social distance by alluding to the girl’s noble father, and her mother’s high-born looks. He continues complimenting the shepherdess on her beauty. She reasserts the social distance between them, firmly aligning herself with the peasantry. She also sarcastically comments on some knights who don’t deserve their noble status.

The knight then avoids the social issue by describing the girl’s beauty and charms as magical gifts from a fairy, and he makes his first direct sexual proposition. The shepherdess courteously thanks him for his praise of her, but conjoins this with a harsh and mocking refusal (Bada, fol, bada!)

The knight presses her further, saying that in his experience peasant girls eventually relent and give in. He proposes that they both be open and honest with each other. The shepherdess retorts that men intent upon seduction are incorrigible liars, and that his praise of her has but one purpose: her sexual defloration (despieuselatje). She refuses to trade her virginity for the reputation of a whore (nom de putaina).

The knight then turns to the argument of “nature.” All creatures are true to type, and eventually revert to what they were born to be. The unspoken suggestion in his words is that the shepherdess’s mother was a whore who slept with a knight, and therefore this character trait is something innate in the woman’s daughter. He proposes that they retire to a small nearby shelter where she may “sweetly yield” to him (per far la cauza dossayna).

The girl refuses on moral grounds, once again mentioning their different social ranks, and how persons should keep to their own kind. She points to the traditional wisdom about the necessity of maintaining status and degree in a society, thus deftly using an aristocratic argument to defend her peasant dignity. The knight expresses his frustration with her coldness and rigidity, and the shepherdess dismisses him without further ado, making a mordant reference to one who gazes stupidly at a picture, or who longs with unsatisfied hunger for manna that does not come. The imagery in these last words of hers seems to suggest that factitious pictures and absurd hopes are the province of foolish noblemen who lie to others and to themselves, but that these baubles hold no allure for the sensible and hard-headed peasantry. The chaste shepherdess thoroughly trounces the lecherous knight in this encounter, in keeping with the moralistic tone of much of Marcabru’s poetry.

—J.S.S.

First published in TRINACRIA, Issue #16 (Fall 2016).

Joseph S. Salemi has published five books of poetry, and his poems, translations and scholarly articles have appeared in over one hundred publications world-wide. He is the editor of the literary magazine TRINACRIA. He teaches in the Department of Humanities at New York University and in the Department of Classical Languages at Hunter College.

For quite a while, under the tutelage of a very important woman professor of the old Sorbonne, I lived, as it were, among the ancient Poètes Provenceaux who were then my daily bread. I can therefore assure every reader that Dr. Salemi has perfectly rendered their spirit, to the point that I find myself deeply moved by this beautiful occasion to revisit the charm and, indeed, the power of this poetry which, in its day, had inspired all of Europe and the Stilnovisti themselves.

The great lesson of the Ars Poetica Nova comes full circle as Dr. Salemi opens for us the treasure chest of early Troubadour song, but with an understanding, finesse, and respect for the spirit of Provençal poetry of which only the most cultivated lover and possessor of languages is capable.

Truly, Dr. Salemi’s historical title of “Professor of the Ars Poetica Nova”—recalling the role Ronsard had played for the Pléiade—could not be more beautifully affirmed than here, in this bravura demonstration of lyrical “jouissance.”

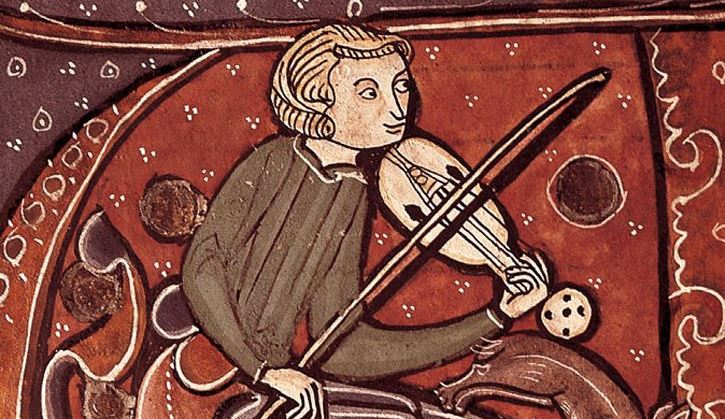

Of course, the graphic for this posting was carefully selected to remind us that Troubadours sang their lays accompanied by a variety of instruments. We have a pretty good idea of how these poems were performed, thanks to the tireless researches of today’s many specialists working in the field of early langue d’oc and Old Occitan poetry.

Here is a link to a historically informed performance of “L’autrier just’una sebissa.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1DzqIUoxxJ8

There you go again, Joe, exposing us to traditions of which we’d barely dreamt. It almost makes me glad to play the frustrated knight.

Ha, ha, ha! It’s interesting too, that Dr. Salemi selected such an early example, perhaps the first of the Troubadours whose works have survived. The choice of Marcabru is definitely how a professor of languages would go about it—all the elements characteristic of the whole tradition already being quite present here at its

onset—probably the best way to “expose” the tradition.

Superb execution; highly effective.

In fact, and I say this because Marcabru is rather early, a poet as much of the Crusades as the Reconquista—it is the latter that makes him even more interesting to me as I am constantly researching the Spanish origins of our New Mexico “alabados” of which, in my mind, Marcabru’s “Pax in nomine Domini!” is certainly intriguing—he is correcting the less than perfect morals of the crusading courts returning back to the regions of France from places and people whose influence was doubtless corrosive of good Christian conduct.

And, of course, Chrétien de Troyes would be hired just for this purpose.

What is truly exciting to me about Marcabru and his imitators is how a major theme of the late Trouvères (moving toward the “langue d’oil” now)—perfectly represented here in Dr. Salemi’s selection and translation—is already present or suggested, and that is the theme of “La Belle Dame Sans Merci.”

It does seem that the real art of the translator consists in the selection. There is a way in which anyone can come up with a translation (obviously normally not as exquisite as we see in Joseph Salemi’s work, alas), but a good selection of what to translate can really open up a world of engagement with the first rites and functions of poetry, in this case the poet as a kind of legislator and arbiter of morality.

By the way, Marcabru may have been martyred for his defense of purity, rather like St. John the Baptist.

Thanks for the wonderful translation. One question: what is the source of the image on the top? It looks like an early Troubador illustration, but if you have any information I’d be very curious to learn.

I’m sorry, but I don’t know. Mr. Mantyk chooses all illustrations for the SCP, so perhaps he could tell you. Thank you for your comment.

Thanks Joseph for your kind reply. In that case, how should I contact Evan Mantyk about this?

KH, contact Evan at:

[email protected]

Thanks Mike!