Translations from Belarusian by the poet’s son Ihar Kazak.

The Explosion

May mayhem never strike our good Earth;

The fertile one deserves tranquility and gratitude,

So that on earth where in ruins weeds give birth,

There would be no malevolent attitude.

But evil—

an explosion…

Again

a wormwood*

spill.

Fear… What abyss for our populous world’s race!

Indeed, fatal is this abyss!

Humanity—it seems to them—has conquered space!

But the enraged atom is on its throne and much amiss.

But evil—

an explosion…

Again

a wormwood

spill.

1968

*Wormwood—anything bitter or grievous (Webster); in Belarusian it is known as byl’nik or byl’nyog, the chernobyl’ plant—a prophetic statement since it was written in the mid-sixties before the Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

ВЫБУХ

Хай ня будзе бязладзьдзя на лобрай зямлі:

Пладаноснай—спакой у падзяку,

Каб на ёй, дзе руіны травой параслі,

Ня было-б аніякага знаку.

А злыбедай—

выбух…

Ізноў

быльнёг

выбег.

Страх, якое прадоньне на люднай зямлі!

Так, фатальнае тое прадоньне!

Людскі космас—здаецца ім—перамаглі,

А разьюшаны атам—на троне.

А злыбедай—

выбух…

Ізноў

быльнёг

выбег.

Inspiration Cannot Be Bought

Inspiration cannot be bought.

You get it only through love.

But when it comes to naught,

You won’t get even part thereof.

There’s no appeal

In verse dull and disparate

You’ll feel your weakness but so real

In poetry anemic and lacking merit.

Its words so cold…

Devoid of music and life’s verve,

The feeling can’t be told,

Its vapor and gloom touch your nerve.

Even your soul tumbles

As in an allegro polka tune.

Will all go well after these fumbles?

Will all these sores heal soon?

Inspiration, my dear one,

Let your roots grow!

May one keep one’s place in the sun

By creative fervor’s glow.

1974

НАТХНЕНЬНЕ НЯ КУПЛЯЕЦЦА

Натхненьне ня куплчецца—

Бярэш любоўю толькі.

Калі яно губляецца,

Ня возьмеш нават долькі:

Ніякае прывабнасьці

Ў радкох сухіх, няроўных.

Пачуеш свае слабасьцт

На вершах малакроўных.

І слова ў іх халоднае—

Бяз музыкі, бяз соку,

І пачуцьцё галоднае,

Ці добра ўсё згуляецца?

Ці пазаціхнуць болькі?

Натхненьне, маё золатка,

Пусьці сваё карэньне!

Хаё будзе сэрцу соладка

Праз творчае гарэньне.

Poet’s Biography

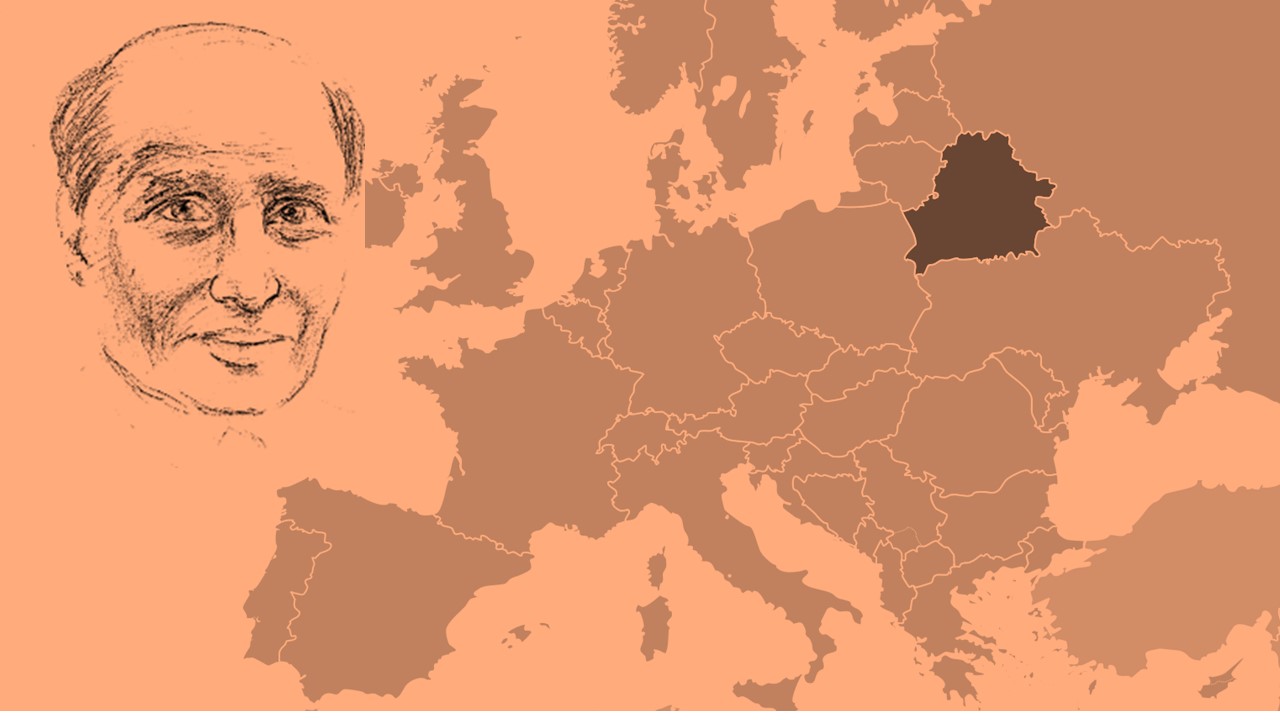

Born near Sluck, Belarus, on December 3, 1907, Ryhor Krushyna [pseud. of Ryhor Kazak] was the first Belarusian writer-poet to become a member of the International PEN Club in 1966. Before that achievement, the poet had to leave his homeland, endure life in forced labor camps in Germany during the war, and to become a displaced person in post-war Europe prior to coming to the United States.

In the early 1920s, he and his older brother, Mikola, participated as teenagers in the Sluck Uprising against the Bolshevik regime led by Juri Listapad. Because of his age, the newly founded Soviet regime did not pursue his conviction. One poem, “Paustan’!” [“Rebel!”] which he published in his underground newsletter and is ascribed to his brother (under the pseudonym Maly Jazep), has been preserved.

Later he joined the literary movement “Maladnjak,” which was soon disbanded by the government. Ultimately, his poetic talent was muzzled and he had to write “for the desk drawer,” which was the common saying then for works by politically unacceptable and unpublished poets and writers.

During WWII he was able to come to the West, and this is where the poet’s activity and his fame as Ryhor Krushyna began. Starting with his first book of poetry, The Black Swan, which symbolized through this metaphor the life of an émigré, he created another six additional books during his lifetime; three works were posthumously published in Belarus after the break-up of the Soviet Union. He has also translated from the Polish, German, Russian, and Ukrainian. He was among the first founders of the Belarusian Institute of the Sciences and Art in North America.

Truly innovative, Krushyna was first to introduce the concept of hyper-dactylic rhyme in Belarusian poetry. He could easily write verse with all the words starting with the same letter, was able to have inter-rhyme capability of all stanzas up to twenty, could write verse that was read from beginning and end (palindromes), and was a forerunner in and experimented with haiku, canzone, sextain and other forms, which were only later picked up by Belarusian poets. His poetry is lyrical and universal, yet it is alive with the Belarusian spirit and love for his Homeland. His poetry is imbued with a tender and all-encompassing love for a tortured land and its suffering people.

Krushyna’s poetry has been translated by his son, Ihar Kazak (pseud.) or Igor Gregory Kozak, a poet-writer and literary translator, who has translated from Russian such émigré authors as Artsibashev, Averchenko, Teffi, et al, and from Belarusian: Bykov, Levanovich, Skobla, et al. In the poetry field, Ihar Kazak has recently been included in the anthology Shadow and Light: 2017 Savant Poetry Anthology, and has also captured one of the prizes in the Gabo Prize for Translation of Poetry for 2018.

Ihar has now compiled and translated Belarusian poetry: Love for the Homeland: A Collection of Belarusian Poetry of Ryhor Krushyna. This, Ihar’s most ambitious project, is awaiting a publisher.

Contact:

Ihar Kazak

POB 530974

St. Petersburg, FL 33747

[email protected]

Słuck was a Polish-Lithuanian town owned by the Olelkovich and Radziwiłł families, the latter from which I am descended. 150 years ago Belarusian peasants didn’t know who they were ethnically, as they had no national consciousness until the late 19th century. The nobility considered themselves Polish-Lithuanian. Peasants were just farm animals, treated worse than American Blacks in the antebellum South. A noble could strangle a peasant and throw his body into a ditch without penalty.

Dostoevsky’s father was a Polish-Lithuanian noble whose peasants hated him so much they stuffed two bottles of vodka down his throat and made him choke on it until he died in hell. The nobles, though, were your organic leaders who knew how to lead and died like badasses. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HeaQzfE2kHw

I like the first poem and translation the most. Thank you for sharing.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-9x5ADYWXeo

I thank the talented Mr. Ihar Kazak for giving us two Belarusian poems of his father Ryhor Krushyna, and likewise a brief, informative prose bio of him. I was interested to learn of the hyperdactylic rhyme (e. g. nationally/rationally, with the accent on the fourth syllable from the end) he introduced to Belarusian literature, which had surged in Modernist Russian poetry at the beginning of the 20th century, and inter-stanzaic rhyme, which I myself am partial too. I was also pleased to read the names of Belarusian figures Bykov, Levanovich, and Skobla, which I could, if time permits, research as well. I must admit I have come late to Belarusian literature, and the only figures I had come into contact with were Jánka Kupála…

After Jánka Kupála (1882-1942)

O, say, who goes there now amidst that mighty throng. Declare

what loads those feet, bast-sandaled, and those strong, lean shoulders bear.

And tell me, Byelorussia, all the troubles you’ve endured,

what bloody stains are on those hands, and in what walls immured.

Articulate where their hard grievances are now unhurled.

Do they vent their injustices to the edge of the World?

Announce who has those millions schooled in pain and suffering.

Express that cruelty that has roused them from slumbering.

Proclaim as well just what it is that they’ve so long pined for:

the deaf, the blind, scorned through the years, to be called human, o!

…and Svetlana Alexievich, who writes in Russian, and who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2015.

Svetlana Alexievich

She dwelt in that flat wooded plat of sand, clay, flax and grain,

in Belarus near Russia’s stretch across from the Ukraine.

From youth she heard the stories o’ th’ Great Patriotic War,

of women who had lost their men, the struggles and the gore;

from interviews, she wove her novels, voices from the time,

unwomanly the horrors, but still touched with the sublime.

Likewise she took up other tales, Chernobyl and the fall,

the Socialist Atlantis sinking in the raging squall,

the hopeless stand, Afghanistan, the communistic plain,

the plan for freedom, ebbing red utopia of pain.

Herself, like all those voices, catch-words, phrases from the ditch,

that polyphone of life—Svetlana Alexievich.

It was sobering to learn, that although Belarusians study the Belarusian language, the number of native speakers, out of a population of some 9,000,000 is only about 1,000,000; and so the lone Belarusian writer to receive the Nobel Prize for literature writes in Russian, which I gather has become the dominant language of Belarus; though as for that the Cyrillic White Russian alphabet sits quite nicely with Russian, and the other Cyrillic users like those in Serbia, Ukraine, and Bulgaria. For comparison, in Ireland, I believe it is < 1% that are native Irish speakers, though, of course, many more speak and understand Irish.