by T.M. Moore

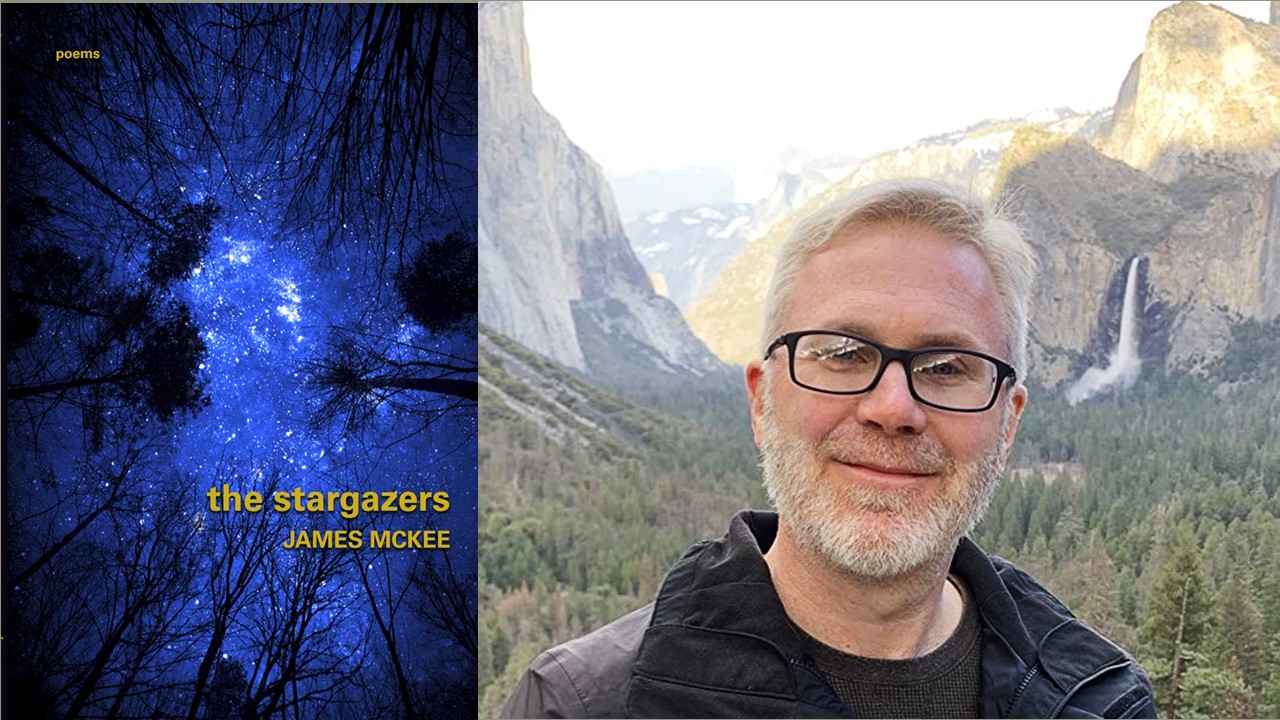

James McKee, The Stargazers (Atmosphere Press, 2020), $17.99

James McKee’s inaugural foray into verse publishing offers a panoply of poetic forms, themes, images, and delights. The Stargazers offers a range of poetic vision and insight, a mastery of words and forms, and an array of subjects assembled into a kind of verse Wunderkammer with a little something for every lover of poetry. His subjects range from the brutality of murder to the banality of urban life; the intimacy of married love to the inevitability of change; and the interiority of the human person, the interaction of culture and creation, and the immensity and wonder of the cosmos.

In short, James is all over the board in a serious but fun romp of rhymes, rhythms, and rapturous reflections on this crazy and amazing world. I asked James about his overarching burden as a poet:

“Although it had been my ambition to be a writer from early on, I did not begin to write poetry in a serious way until relatively late, in my early thirties. I took it up simply because reading it gave me the greatest pleasure, and I wanted to return the favor, as it were, by creating work that others might enjoy as well. And once I started paying real attention to meters, stanzas and the like, love of the craft claimed me, and that was that.

“As for the burden a poet carries, Horace tells us quite truly that because poetry is a luxury, it must either excel or be worthless, and because I have no doubt that this is the case, I think the poet’s one unshirkable duty is to write well. That is to say, she or he must use words in such a way that the reader will emerge from the poem illuminated, refreshed, moved, delighted. Changed. To write as a poet writes is to write from love, both of this sad and beautiful world and of the language wherein the poet discovers her or his truest being.”

The Stargazers fulfills this burden and hope in grand style. In his verse, we sense James’ love for history, and for remote and exotic places—and the mystery that attends them. His observations are spot-on on the casual beauty and conflicts of urban landscapes, the depth of depravity in the human soul, and such vexing issues as immigration, exploitation of workers, the problem of growing old. Like I said, there’s something for everyone here, and each poem is guaranteed to challenge the reader’s thinking, and to keep us picking at his verses until we liberate their inherent delight and they flood our souls with insight and pleasure.

I discerned an influence of Gerard Manley Hopkins in some of The Stargazers’ themes and turns of phrase. James happily owned the debt to the Jesuit priest. I asked him about other poetic influences:

“Wallace Stevens was the first poet I read with something like unimpeded and inexhaustible delight, and the prismatic sensuousness of his work remains a continual source of inspiration. Robert Frost and Philip Larkin are, to me, the two greatest craftsmen of the lyric in English of the last century, and I consult their examples regularly. To read Emily Dickinson is to be, again and again, thrilled and astonished as with no other poet. At one time or another in the past, I have had periods of obsession with the work of Yeats, Tennyson, Dryden, Wordsworth, Milton, Hardy, and I continue to read them with the greatest pleasure. And last (since this list is getting too long!), I will mention two poets to whose work I came late but who nevertheless seem to mean more and more to me: Elizabeth Bishop and Walt Whitman.”

I have a natural interest in poems about the poetic process. The first poem in The Stargazers is a meditation on building a house, though one suspects the house in question is the book that follows. James tells us that he intends, concerning his poems, to “bank them round like a nest/with stray chipped bricks…” He tells us that the rooms in his house “draw a force to hold, like a home’s./Even the view belongs to you now.” Crafting a poem is a matter of capturing “armatures of fact” as they “bare themselves to us best/within brackets of as if…” (“Poem in Which the Word Truth Does Not Appear: An Art of Poetry”). He celebrates the stickiness of poetry in “Made New”, and he provides an insight into his poetic beginnings – in defying authority figures to say whatever he wanted—in “Authority Figure”.

James is troubled by the depths of human depravity. He celebrates the death of Colonel Gadaffi, but rues the brutality and hatefulness by which it was accomplished, feeling himself a bit “diminished” by the stark and gruesome photographs of the murdered dictator. He perhaps ascribes the inhumanity of this act to the fact that we’re all a bit like the crow: nothing much to crow about really, and quick to bully other creatures, just for the fun of it. He asks,

But to whom are a crow’s joys

not known,

when free to despoil

for sport alone?

This same theme is glanced in “Through the Ruins,” “The Donkeys of Petra,” “In the Ruins of a Tyrant’s Palace”—in which he denounces Tiberius as he himself casually swipes a bit of the ruin for his desk – and “Leaving Anne Frank’s House”—where he expresses disappointment that the last thing you encounter there is the gift shop, thus violating the sacred space for commercial ends.

Culture and creation struggle in certain of the poems of The Stargazers. Culture—especially urban culture—is banal, bullying, and blighting, while creation is tenacious, tantalizing, and even, at times, triumphant. A “sawed-off sumac” branch clings to its chain-link tormentors, like Paul Newman getting up from George Kennedy’s pasting over and over again in Cool Hand Luke (“Morning Commute with Revenant.”) A hummingbird shows up in Queens and brings sudden but fleeting delight:

I saw a hummingbird last week, which was weird:

a hovering emerald, exotic even for Queens.

Something like joy rayed through me, only to disappear

since wherever its wing-blur belonged, it wasn’t here.

I try, but cannot not know what it meant. Means.

(Catch that Hopkins-esque “wing-blur”? And that double negative? Love it.)

His poem “The Warthog” disgusts, but, at the same time, entertains, even as it points in our direction. The image of the hog defecating nonchalantly reminds me of a Rembrandt etching of the Good Samaritan, with a dog defecating in the foreground. I can’t help wondering if James didn’t pick up on that, too, since he uses the word “Rebrand,” capitalized, in a subsequent line.

As I have just passed my 71st birthday, the poem “Departure” was especially poignant for me. I think my attitude toward the inevitability of getting older is the same as James’: It can be a struggle, you have to leave a lot behind, and you might not know what lies beyond the beach of this life; but, big deal:

Like escaping through a siege, growing older

hampers itself with hopes of return;

so if, over your bare shoulder,

upwind palaces start to smolder,

let them burn.

The poems report on places James has visited, and historical scenes he’d like to relive. Among these are some of the most delightful images in the collection. Here, for example, James describes the St. Lawrence river, as seen from the heights of Montreal (“Climbing Mount Royal”):

…how the St. Lawrence runs

like a gash, stitched with bridge metal

across tar and cement accretions.

He describes the shadows, coming over Masada, as creeping “like wet ink beneath olive-drab scrub…” (“The Road to Lake Avenue”). The whole-poem image of Adam and Eve returning from their lostness for a peek inside the barricaded paradise, and the power of that glimpse of lost uprightness to change them even now, is large and powerful:

…in silence, they returned together

to their fields, their hut, and their two boys,

who had never known their parents so tender.

James has a word for conservatives: Change happens, so “good luck dodging the frivolity it brings” (“Going with the Flow”). Again, in “Nothing to Do Now but Wait,” winter has to get its mind around the fact that spring is coming, and everything is going to change. Maybe not right away, or when we’d hoped (I’m reminded of Andrew Wyeth’s painting, “Cold Spring”), but inevitably:

Change must soon come.

With winter done,

on each dark bough

green fuzz will form

as winds grow warm.

Soon. But not now.

“The Stargazers,” the antepenultimate poem in the collection, gathers many of the themes of the collection into one astonished night of looking at the sky in Yucatán. Travel, the glory of creation (and lamenting the light pollution of a city night), the comparison of skies and city lights, the brevity of life, and the wonder and immensity of being: all show up for a final bow. The effect of this poem is to make us wonder what we missed in the preceding pages, and to lead us to revisit each verse with more patience and attention.

The Stargazers is pure delight. It is both intellectually stimulating and affectively stretching. The more I read the poems, the more insight and pleasure they yield. Even the comic elements—his falling off a donkey, the cherub advising Adam and Eve to “Watch out for the sword,” and more—make the serious themes of the poem come alive. James McKee has acquitted himself well in this inaugural effort. We may hope for more of the same to come.

T.M. and Susie Moore make their home in the Champlain Valley of Vermont. He is Principal of The Fellowship of Ailbe, and the author of 8 books of poetry. He and Susie have collaborated on more than 30 books, which may be found, together with their many other writings and resources, including the daily teaching letter Scriptorium, at www.ailbe.org.