.

Martyred daughter of a libeled Czar,

You for whom St. Basil’s bells have rung,

Condemned to die dishonored and unsung,

Yet gentlest of the Romanovs by far

In silent black-and-white forever young.

It seems your life was but a royal dream

Of gold tiaras wrought by Cartier

And gilded Easter eggs from Fabergé,

Caviar, ballet, a proud regime

Of nobles waltzing as musicians play.

But life became a fairytale deformed

Once revolutionaries seized control—

Your family disgraced then butchered whole;

Your palaces destroyed, the Kremlin stormed—

A brutal murder of the Russian soul.

Your legend grew. The princess lived and fled!

Her memories erased, she came to France

Whence she would rise again! The smallest chance

The antique Russian world was not quite dead!

But that was just a dream of fond romance.

This elegy grieves for a world long gone—

A world whose faith and honor were repealed,

A Russia wrecked by war and left unhealed,

Where brutal bullets tore the hope from dawn

As Bolshevik betrayal was revealed.

If only, Anastasia, you had fled

with some young soldier—loyal as a knight—

To fight and banish Lenin’s hateful blight

And raise you up to rule as Queen instead…

Well, that’s the ending I would choose to write.

.

.

Brian Yapko is a lawyer who also writes poetry. He lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

A very beautiful and touching poem on the murdered Grand Duchess.

Her first name means “Resurrection.” I have often wondered if the many stories of her supposed survival were in some way prompted by that name.

Thank you very much! I did not know that Anastasia means “Resurrection” so that makes me doubly pleased to have this poem presented soon after Easter. I’ve always been fascinated by the Romanovs and their sad fate. Before DNA testing came about, I hoped very much that the Anna Anderson amnesia story was true and that she had indeed survived.

Brian, it pains me to say this, but Anastasia did not survive. Not a single member of the Romanov royal family escaped that cellar in Ekaterinberg. All of them were shot and bayoneted by the Communist thugs, and their bodies partially cremated and buried in a nearby forested area. This included the Czar, the Czarina, their three daughters, the young Czarevich, the family doctor, and some servants.

Truly a “brutal murder of the Russian soul.” I’m glad that the Romanov family has been canonized as martyrs for the faith and that their honor, at least, has been restored.

Such a graceful poem, and a good thought! I have often wondered if Anastasia did survive; there were so many reports of it, and many decent people who could have helped her. Thanks for reminding us of how the roots of what we are now experiencing came to be. From the very first moments beauty was disregarded, and it became almost impossible to create. Of course this is now shrouded in the mists of

history, while we are being carfully taught that even

yesterday has no relevance. Again, thanks for reminding us.

Thank you very much, Sally. I believe that the roots of the collapse of civilization that we are experiencing now did indeed start with World War I and the Bolshevik Revolution. In their wake, elegance and modesty were lost to the Jazz Age and religion became unfashionable in Western Europe and expressly inimical to the state in the newly formed Soviet Union. The price civilization has paid for the anarchy and nihilism of revolutionaries is high indeed.

Brian, I echo Dr. Salemi’s observation that your poem is beautiful and touching. The language flows along mellifluously and effortlessly, with your adept use of literary device adding to the aural experience. I also love the rhyme scheme… the abbab that stops short of ending in a clunky couplet is perfect. The technicalities all add to your depiction of the subject matter and never detract from its message. I like the way you personally address Anastasia – it connects the reader immediately to the historic horrors making the third stanza a real punch in the gut. Your closing stanza, and especially the final line, is heart-rending.

“But life became a fairytale deformed/Once revolutionaries seized control” is still ringing around my head. As I’m sure you intended, it serves as a grave warning to all of us today.

Very well done, indeed. This poem is an absolute privilege to read.

Susan, thank you so much! I am so grateful for your kindness and your insights! I’m especially glad you liked the rhyme scheme. I struggled with it a bit because I originally envisioned the poem as having six lines per stanza. But then I came to cutting the stanza cut short to reflect the tragedy of the Romanovs. As far as the content, as I think you have probably guessed by now, I have a deep disdain for revolution and anarchy. I am especially disgusted by the mob attacking — and too often killing — innocent people as symbols or scapegoats. Why did Anastasia Romanov — or her siblings, or her parents for that matter — deserve to be executed at the age of 17 in a brutal, cowardly fashion? And what perverse mindset made the revolutionaries think this was a good and justified thing? And to what extent does this toxic mindset now exist today?

Brian, I am with you all the way on the mindless evil of mob attack. I have this theory that we are all here to learn a lesson from life – that lesson lies within our continuous cycle of repeated mistakes. All the time the truth is spurned, and all the time our past is burned, and all the time the people continue to believe those who rewrite our history, we will proceed along the same path to our inevitable destruction. I’m sure the Bible or The Bard say this much better than I can… but, the mere thought of this well-trodden path sends chills. I veer from it quite frequently these days. I quake… but feel all the better for it. And, once again, I thank this site for allowing freedom of speech.

Susan, I think you are 100% right about learning lessons and that this can only happen when we confront history with both eyes open. I also echo your gratitude to SCP for allowing us that freedom of speech.

I ECHO THE HEARTWARMING COMMENTS OF SUSAN BRYANT JARVIS.

AS JOSEPH S SALEMI REMINDS US ; ANASTASIA MEANS RESURRECTION; AND SO VERY APPROPRIATE SO SOON AFTER EASTER.

Thank you very much, Donald.

Thank you so much, Brian. I started reading Anastasia books as a child, and shared hope for her escape. To me, the most powerful line here is, “A brutal murder of the Russian soul.” That’s at the center or heart of your poem, and immediately afterward you write, “Your legend grew.” As she and her family are twice canonized, as martyrs and as “passion-bearers,” Anastasia now has a saint’s legend in the facts, as well as the legend to which we dreamed of a better ending.

I have one suggestion. I would change line 22 to “A world whose faith and honor were repealed.” “Where” instead of “whose” implies that the “world long gone” was a place where faith and honor were regularly repealed–but the revolution did that. For anyone interested in old Russia, I recommend several Russian sonnets (in English) by Maurice Baring, who was a journalist there, and loved the place like his homeland. His poems are loving snapshots of that lost world.

Thank you, Margaret! Gosh, I wish I had thought of your suggestion, because you are absolutely right and if I had it to do over again before publication I would change that “where” to a “whose.” Now that I’ve read the poem over again I can see why it could be misinterpreted.

I know well about the canonization of the Romanovs. I had the privilege of visiting their tombs at the Fortress of Peter and Paul in St. Petersburg. Alexei and Anastasia are not there because their remains are still being questioned by the Russian Orthodox Church. However, the rest of the family’s tombs are greatly venerated and there are all kinds of icons offered depicting the martyred family.

Thank you for the referral to Mr. Baring’s poetry. I’ll look him up!

Our moderator can change a word at the poet’s request, and may do so if he sees your wish expressed here. If he doesn’t, you can ask him at [email protected]

Thank you, Margaret. I’m pleased to say that Mike has made the change you suggested and it’s now a better poem thanks to you!

The English author H.H. Munro (also known by his pen name of “Saki”) loved old Russia too. He spoke the language, and wrote extensively about Russia’s history.

Joe S., thank you for this referral to Mr. Munro. I will look him up. I am indeed fascinated by Russian history — more specifically, pre-Soviet Russian history. The tragic story of Nicholas and Alexandra has especially touched me since I was barely in my teens. But I’m also fascinated by Peter the Great and Catherine the Great.

Excellent, Brian. Poor Russia. I have one question, though (for which you may exile me to Siberia if you want): In line 1 of stanza 5, what is your analysis of the metrics there? I couldn’t figure it out. You don’t have to have a good ready answer. The (forbidden) syllable count is correct, but the metrical feet are hard to add up.

Thank you, C.B. Of course I won’t exile you to Siberia! Now that I have re-read the line, I can certainly see why you question the meter. Indeed, thank you for forcing me to really look at it and understand what I did from a technical standpoint. When I’ve spoken the poem out loud my meter is close to how Mike describes it in his response to your comment. But my analysis is slightly different. I scan it this way:

“This el (iam) e-gy (pyrrhic) grieves for (spondee) a world (iam) long gone (iam.)”

Five feet, five stresses (EL, GRIEVES, FOR, WORLD, GONE) but with the spondee of the third foot stealing one of the stresses from the second foot.

Where I differ with Mike’s analysis is that I don’t think the two unstressed syllables in “elegy” fit with either of the adjacent feet, so that’s why I consider it pyrrhic. If it was an anapest it would only leave four feet when I did intend five feet, five stresses. In my analysis, it does actually have five feet — the only transgression being that one of the feet has no stresses (something which I understand is allowed in ancient Greek poetry.) What should have been an iam has its stresses taken over by the two stresses of “grieves for” spondee. One could preserve the iams more directly by reading “elegy” as EL-e-GEE but that sounds wildly inappropriate to the piece. So, in sum, I’ve left the second and third syllables of “elegy” as metrical orphans who have been adopted by the next foot.

Forgive me if I seem to be just rationalizing an ex post facto defense. Maybe I should tinker with it a bit more, but I have to confess that I like the line the way it is, despite its irregularity. For me the rhythm faltering a bit it adds a wistful quality and seems to confirm that something is not quite right in the world. I hope it’s not seen as doing damage to the poem.

Thank you again. You really made me think!

I read Mike’s comment, and I agree completely. The line is not unharmonious, for mysterious reasons. I’m not sure whether even Milton could have come up with a metrical variation like this one, but if it works, it works.

The difference between reasons and rationalizations you note earlier is very important.

Your own analysis of your own line leads to the question: Should this be considered a legit example of metrical substitution or just a one-off that happened to work? I don’t have the answers, but I’m sure as hell happy to hear from someone who is, by disposition, inclined to attend to details and bring a discussion to its proper conclusion.

C.B., I’m humbled to be mentioned (even in passing) in the same paragraph as Milton — especially since my mystery line was written by accident/instinct/the muse… who can say? But I’m glad it works and I thank you for helping me see this through. I don’t want to be sloppy or unthoughtful in my work because I labor over my poetry — a true labor of love in which I aspire to be as meticulous as I know you are (as well as other accomplished poets on this site.) I appreciate your keeping me honest. I have much to learn.

Brian… first this is a beautiful poem.

C.B. I’m going to take a shot at this. I think the construction of the line is something like this:

This el…egy grieves…for a world…long gone—

iamb anapest anapest spondee

Of course, I’m sure there are other possible ways to parse it.

It’s odd that there are only four metric feet in the line when all the other lines are iambic pentameter, and yet, I didn’t pull up on the line at all. I have no idea why. I think it’s amazing that you found it. I guess this is one of those instances when metrical variation just works.

Of course, I might have it all wrong!

Thanks, C.B.

Maybe the final spondee reads as two feet?

Thank you, Mike. And thank you for your analysis which I think is a good one. I appreciate your taking the time and effort to go through that line with a critical eye! I did analyze it somewhat differently (if you read my response to C.B.’s comment) but either way, I hope it works! And thank you for taking care of the word change that Margaret had suggested!

Mike, your metrical analysis is what mine would be–and I have an idea why neither you nor I nor Brian pulled up on this line when we read it. There are only four metrical feet here, but with a spondee, there are five stresses. The poem is pentameter; what we want to hear is five stresses, and we find them. Good readers of English are listening for stresses, not counting syllables or analyzing how many feet we find.

Another factor at work here is the length (or quantity) of those two final words, “long gone.” It takes considerable time to say these words. Quantity rarely counts for much in English scansion, but here it does. The line is lacking a foot, but not only are there enough stresses, there is also quantity that makes the line stretch out quite long enough for the poet’s chosen meter. Brian’s ear was satisfied, and so are ours. I would call this a line where metrical analysis reveals an anomaly, but the meter remains acceptable. And I would also say this is an unusual thing not to be planned or justified as a pleasing metrical variation. It just works that way.

Margaret, I really appreciate your explanation. You’ve cleared it all up. I also think it helps that it is the first line of the verse.

Thank you, Margaret. Even though I wrote this, it’s been a bit of a struggle to understand precisely what I did metrically, so I’m very grateful for your explanation. I’m even more grateful that the poem still works even with the anomaly!

Dear Brian,

I really like this piece. You tapped into some good story-telling power, and really created something original with very fine sensibility.

There is murder, betrayal, innocence, and yet it’s all handled with grace and beauty, like a true poet. That’s so important. Too many writers today just try to share their feelings, and try to create some kind of novelty, an effect. But you really made the thing your own with the closing line about longing to re-write history, how you would have rewritten that history. That gives the poem that special magical touch, and a quality of wonder.

It’s an important question: how can we find the magic? We often want to say this or that thing, but often I think it’s a question of letting go of any concept per se and just wondering, how can I find the magic, what’s needed to imbue this work with something magical? From there the concepts resolve themselves, and so does the poetry. We don’t have to chase it, it finds us.

I think this is a great example of that. The poetry clearly found you.

Thank you, David. I so appreciate your encouragement. You’re right — it’s so hard to find that magic. But I find when I write about things that I love or am passionate about, that certainly helps. With this particular poem, the tragedy of the Romanovs has touched my heart for decades. I was finally inspired to write about.

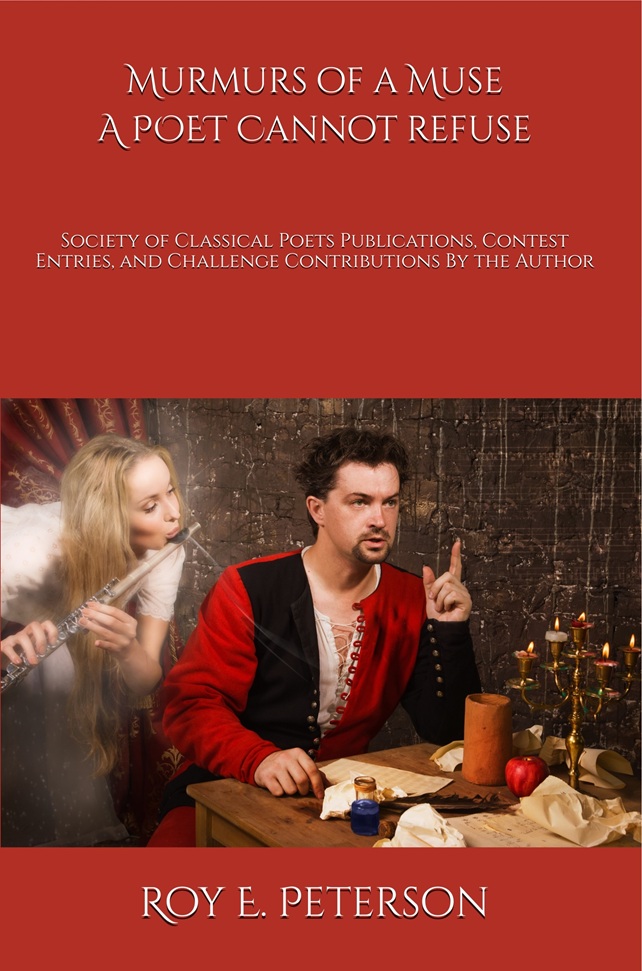

Great poem, good job! There are all kinds of layers I enjoy in this poem; the history lesson, the story telling and the poetry itself, and the musings and insights into “the Russian soul” and events that could have been and would have satisfied a human sense of righteousness and justice if they would have been. Your poem is a pleasure to read and I appreciate the picture too.

Thank you very much, Yael! The picture, of course, was provided by the Society. In fact, I would like to compliment the Society for always finding the perfect artwork or photograph to go along with the poems that are published!

I will simply add my voice to the chorus of appreciation for a poem which

relates a shameful event in history, yet leaves the reader with higher thoughts of beauty, and the fleeting possibility of hope.

Thank you very much, David!

The photo is of Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna, not Anastasia.