.

Apophis

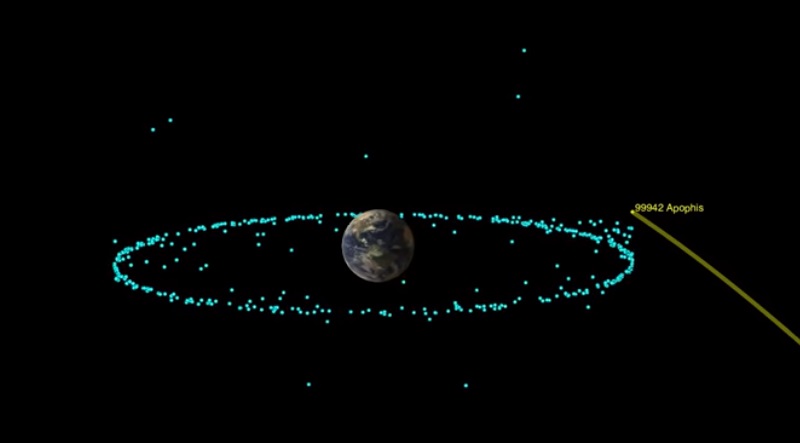

Apophis is the name of a near-earth asteroid that passed by our planet a few months ago, a name it shares with the Ancient Egyptian evil serpent god and one of the Hyksos pharaohs of Egypt.

Apophis, demon-snake,

Foe to truth and light,

Coiled at the cusp of the sky,

Poised where the sun must pass by

To snatch him in your bite;

__Again, when day shall break,

__Your heart shall quake.

Apophis, demon-king,

Foe to ancient gods,

Blood-spilling brute from the waste,

Smiting a nation disgraced

Beneath your crushing rod;

__A day, not far, shall bring

__Your vanquishing.

Apophis, demon-star,

Foe to us, you loom

Hurtling through tumult-filled skies

Inexorably, our demise,

To rain down crashing doom;

__What miracle can bar

__Your fatal hour?

.

.

Io

Hellish orb of woe,

Infernal realm aglow,

__Ablaze with fiery red,

Vast lava-seas that go

In boundless, roiling flow

__From pole to burnt pole, fed

From ash-stained peaks that throw

Cascading magmas, blow

__Out noxious plumes, and spread

A white-hot flood below,

The molten sulfur floe

__Across the fire-sea’s bed,

Which ever surge and grow,

Engulf and overflow,

__With naught but flame to tread.

Your heart of fire, the throe

That stirs it forth you owe

__To Jove, around whom, led

Careening to and fro

In rounds that never slow

__You dance, forever wed.

O, wrathful world! Although

Your flames and fumes are foe

__To life, you are not dead.

No! Rather, they bestow

A living death and show

__That beauty has not fled

But lives to undergo

Such pain, so all may know

__The hell they are to dread.

.

.

Adam Sedia (b. 1984) lives in his native Northwest Indiana, with his wife, Ivana, and their children, and practices law as a civil and appellate litigator. In addition to the Society’s publications, his poems and prose works have appeared in The Chained Muse Review, Indiana Voice Journal, and other literary journals. He is also a composer, and his musical works may be heard on his YouTube channel.

These are two marvelous poems with a most uncommon topic Mr. Sedia. I commend you for effortlessly commixing the topics of astronomy and mythology into a brief, but metaphysical narratives! I was particularly captivated by the final lines of your first poem as they bear a striking parallel to the prophetic warning of an asteroid falling to earth in the Book of Revelations 8:10-11.

——————————-

Apophis, demon-star,

Foe to us, you loom

Hurtling through tumult-filled skies

Inexorably, our demise,

To rain down crashing doom;

__What miracle can bar

__Your fatal hour?

10 The third angel sounded his trumpet, and a great star, blazing like a torch, fell from the sky on a third of the rivers and on the springs of water— 11 the name of the star is Wormwood. A third of the waters turned bitter, and many people died from the waters that had become bitter.

——————————-

Was this parallelism intentional, or is it a merely coincidental observation on my part?

Comparisons aside, may I be so bold to ask whatthe poetic form your poems are written in? After reading them, I couldn’t help feeling curious about the form or style used and why you chose apply it. Once again, I thank you for these great works you have shared, though I couldn’t prevent myself from writing a few quatrains inspired by your poetic pieces.

“We Who Seek the Stars”

We who seek the stars are not at peace

With the earthy ground beneath our knees.

We who seek the stars yearn to fly

Among the stars above the sky.

Dare we explore, dare we deplore

The old views like savants who pore

Over the star spangled pages,

Spread across the heavens for ages.

We who seek the stars wish to reign

Over the stellar and mortal plains.

Yet we who seek the stars are blind

To the grim fate which we’re entwined.

Although your query was addressed to the author, I shall try to answer it. As far as I can tell, this is a nonce form, that is, a stanzaic structure created just for this particular poem, the definition of which lies only in an accurate description of the structure of the stanzas A one-off, you might say. Perhaps Mr. Sedia or someone else will chime in and prove me wrong with a clear historical precedent that has been given a name.

What we have here (in the first poem) is a seven-line stanza with an ABCCBAA rhyme scheme. The lines are mostly iambic trimeter, but the last line in each stanza is dimeter. This might not be totally clear because the author, who is known by most of us here to have a fondness for metrical variation — even if only for its own sake — takes liberties when it comes to carrying out the promise of his initial plan. He’s thrown in quite a few anapests, which may be elided or taken as metrical variations, and in the final stanza he lost the good perfect rhyme. I’m sure he thought it was worth it, because the result is pretty good.

Mr. Anderson, thank you for presenting your interpretation on the techniques used in these poems. I initially assumed some iambic or trochaic meter was applied, although your interpretation was close to what I inferred. However since I am new here, I am unfamiliar with the author’s modus operandi and am therefore sceptical of my conjecture.

Thank you, Ryan, for reading the poems and for your comments (and verses!) – and thank you to CB for his kind words, as well.

As far as form goes, I dislike the term “nonce,” as it carries an implication of capriciousness or whimsy. But CB is right: the forms are indeed idiosyncratic. In my earlier works I liked to let each poem dictate its own form, and these more recent works are hat-tips to my earlier style. “Io” owes its consistent rhyme to a work “Allayne” by the late Kevin Roberts, which I think uses a consistent, driving rhyme to great effect.

As for the meter, CB’s scansion is correct: both poems are iambic, with some slight variation. For a summary of my views on metric variation and its techniques, please read the essay I published on this site earlier:

https://classicalpoets.org/2020/07/13/the-spice-of-life-metric-variation-in-formal-verse-an-essay/

The point of the essay is that metric variation should be used to reflect the natural patterns of speech, as meter itself derives from natural speech patterns.

Finally, I’m glad to see my subtle reference to Wormwood of the Apocalypse has not been lost on the reader. Tie it in with the serpent god and the Egyptian tyrant and you have a more comprehensive, if less straightforward, reference to the episode – at least by way of analogy.

Anyway, thanks to you both again. I very much appreciate all your thoughts.

Thank you for clarifying me on the subject Mr. Sedia and I am glad to that my observations on the symbolic meaning of your poems have been proven correct.

I very much enjoyed the iambic trimeter “Io” as a flowing poem with a well-defined conclusion.

I was waiting with interest for Adam to comment on the form of “Apophis.” I myself use “nonce form” exactly as C. B. Anderson does, with no pejorative implication. It is a very useful term, and others here and elsewhere have used it. However, I am surprised to see no definition of the term either online or in print dictionaries or specialized works such as the Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics. “Nonce word” is more often defined and less useful.

If any pejorative meaning attaches to the word “nonce,” it may come from “nonsense” or “nonsense verse,” as Adam’s comment suggests.

I, too, was immediately fascinated with these forms, especially the parallelism — both in thought and form — of “Apophis”. The imagery is also very beautiful!