.

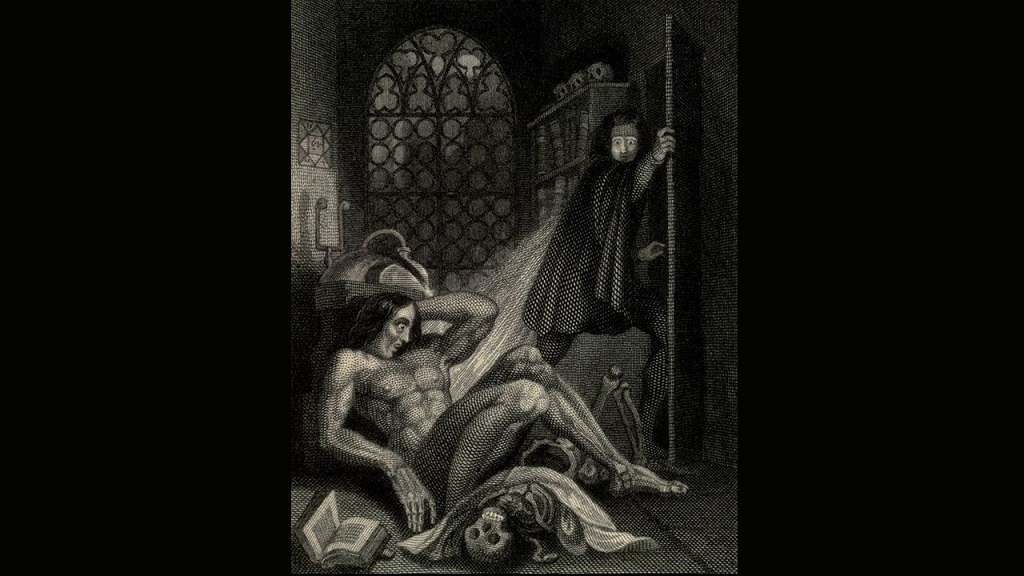

The Modern Prometheus

Grrrr! Linden trees with falling leaves infest

These ancient mountains. Crimson-faced they scream

Like mobs in Transylvanian villages

Which brandish knives and torches. Hate-obsessed,

They yell “the Monster! Nature’s veil is torn!”

Compassion dead, they make me what I seem:

A raging brute who kills and pillages,

From lightning in a dungeon lab reborn.

My hands hurt! Pain! He made them both too big!

My ribs ache from the prying to and fro

Just like the stitches on my neck and head.

My smell offends me, like a butchered pig.

My eyes bulge out, my skin is pale and ghoulish

But I am strong! Much stronger than the slow

And sinful man they hanged till I was dead!

To think I’d let them keep me chained was foolish!

Hot tears! Men mock and ridicule my grief

Despising my contrived humanity

And proving that they’re just as much from Hell

As I, a damned reanimated thief.

The villagers began this savage war

Of bloody horror and insanity.

They’ll chase me till I’m locked up in a cell.

My second death would sate them even more.

Survive! The mountains pull me to climb higher.

I’ll find a lookout from which I can gaze

Upon the valley, some sharp peak or ledge

Where I am safe from pitchforks, guns and fire.

Avoid those poplars turning parchment brown!

They line the river and the cobbled maze

Which leads to Bucharest. No, skirt the edge

Of copse and knoll and shun each heartless town.

I thirst! Cool waters flow beside these rocks.

I’ll think as I sit by this willow tree.

The Master gave me neither love nor grace;

Just grunts and strength as if I were an ox.

I curse Herr Frankenstein whose only goal

Was scientific fame. Just look at me!

This incoherent brain, this ghastly face!

Abomination! And… what of my soul?

Confused! Before I hanged I hoped to learn

What freedom meant. But with this second life

I’m cursed to strike and slaughter to survive,

Unfit for love, my wretched doom to burn.

The wind groans from the castle on the hill.

Such loneliness! Would he build me a wife?

A woman dead like me and yet alive?

No. She’d be just a slave bound to his will.

Despair! My sight is blurred, my heart is ice,

I cannot dream, old memories have died

And naught is left of me before the grave.

Herr Frankenstein, no life is worth this price!

I have no past or future! I shall know

No family, no friendships nor a bride!

My destiny is some dark well or cave

Beneath the moon where only dead things grow.

.

.

Brian Yapko is a lawyer who also writes poetry. He lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Very creative Halloween poem, Brian! Ingenious rhyming scheme, compelling imagery. Thanks for an enjoyable read!

Thank you very much, Paul!

Wonderful poem, Brian. It seems to parallel the present “science” and describes its nefarious results.

The only difference is that your Frankenstein seems to have the remnants of a soul.

The statement after “Confused” is exactly why the

pope’s (?) urging of the abolishment of the death

penalty is so misguided.

I really enjoyed reading this, especially on the feast

of Christ the King.

Thank you very much, jd. I’m especially glad that you recognized my concerns about Science versus the Soul — especially now that Science is willing to enter territories where ethics no longer matter.

Brian, you captured the creature’s predicament perfectly. And as jd stated, it rang of the destructive qualities of certain “scientists ” today. Well done!

Thank you very much, Mo. And a deeply lonely predicament at that.

Terrific poem Brian and good to know that the creature had feelings. I am reminded of the delightful Gene Wilder in the Mel Brooks movie, “Young Frankenstein” or is it “Fronkensteen?” Pitchforks at the ready for tomorrow’s zombie hunt.

Ha ha. Thank you for this fun comment, Jeff. “Young Frankenstein” is one of my favorite comedies of all time and I can quote an embarrassingly large part of the movie. “Putting on the Ritz” still brings tears of laughter and Frau Blucher (neigh-h-h-h-) gets me every time.

Brian, I am stunned by your powerful poem. It is masterful.

Thank you very much, Mary!

Wow, Brian, great job of writing from the creature’s perspective! I never would have thought to do an ABCADBCD rhyme scheme, but it fits here.

Thank you very much, Josh! It’s not easy to feel sorry for him but the Creature’s very existence is full of pathos. As for the rhymes scheme, how do you write poetry for a monster? I didn’t want to do blank verse because I wanted a Poe-like Gothic feel that only rhymes can bring, so I came up with a rhyme scheme that I hoped would be relatively unobtrusive.

Brian, I have immense respect for Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’, and you have afforded the Creature every justice in this fine piece of adeptly crafted poetry. The rhyme scheme is perfect – it’s unintrusive and allows the end rhymes to flow seamlessly along with the body of the work. I love this little bit of internal literary splendor: scientific fame/ incoherent brain… oh how this taps into the essence of today’s new religion.

In fact, your poem shines with the essence of the times, with man playing God with many experimental scientific ventures. I get a transhumanism vibe with these heartrending lines: “The Master gave me neither love nor grace;/Just grunts and strength as if I were an ox.” As I’ve said before, you have the enviable knack of portraying characters vividly and beautifully… you have brought the Creature to life with your superbly wrought words and you have this reader swimming in his thoughts and sympathizing with his predicament… you have made him so real, I can even smell him… that waft of butchered pig has given me goosebumps. I can’t help but imagine that this is what will happen if women are made obsolete, and experimental Science alone is responsible for the next generation. This magnificent poem is a must-read. Very well done, indeed!

Thank you very much indeed, Susan, for this generous comment! First I should say that my poem about The Creature was intended first and foremost as simply a dramatic monologue in his (inner) voice — a point of view and a psychology which is not generally considered. Its sociological and ethical undertones result not from me so much as from the material that it is based on — as you point out — Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein.” But that does not in any way diminish the relevance of your comment and our mutual concern with “transhumanism.” You’re right to focus on my lines about “scientific fame” and “incoherent brain.” I would add one additional line to this discussion: “Abomination… and what of my soul?”– something Frankenstein never once thought about. Humans are souls first and foremost and this is something Science (especially Medicine) generally doesn’t recognize let alone honor. That is why leftists cannot for the life of them understand conservative abhorrence of abortion.

You have zeroed in on an important theme of this poem which comes from Shelley herself — the harm and despair caused by science when it is practiced in an unethical, Godless way. This theme just happens to be more relevant now than it has ever been before — now that we are in a situation where we can not only attempt to change gender through surgery and chemistry, but where we can clone humans, create test-tube babies, use science to inject DNA from one species into another, generate fertility so that a human woman can give birth to 8 children at once… The list of bizarre potentialities is limitless. So much of science (and medicine now, as a subset) is focused on what we “can” do without much concern about whether we “should” do it. The Creature is the least of the monsters we face as a result of many scientists who zealously advocate atheism.

But the divorce of science and spirit is not inevitable. I personally know several scientists who are firm believers in God. We live close to the Los Alamos National Laboratory (where the Manhattan Project was developed and where more Ph.D.s live per capita than any other city in the U.S.A.) and there is a surprisingly substantial population of scientists, engineers etc. who are actually religious. The number of churches in Los Alamos is astonishing. There is no reason why science must be divorced from faith. And there is no reason why medicine should be divorced from ethics.

Thank you again for your comment, Susan. I very much enjoy these discussions of matters of consequence.

A fine take on ‘the creation’ in what I believe may be the first, or one of the first, epistolary-style novels, warning Man not to get above himself.

Thanks for the read.

Thank you very much, Paul. And yet this theme of warning Man not to get above himself goes all the way back to ancient mythology! Hence Shelley’s subtitle “The Modern Prometheus.”

All those years ago, in the Middle East backwater I was in at the time, religious leaders picked up on the name of the space shuttle ‘Challenger’ to explain the disaster, just as boasts of the Titanic being ‘unsinkable’ were seen to be an explanation for the ship’s sinking.

I understand “Titanic” because they claimed it was unsinkable — that “God Himself could not sink that ship.” But “Challenger”?

From the title to the end, your image rich setting and heart-rending telling is a compelling masterpiece of monster introspection with a lesson that man should not mess with creation. Powerful words and phrases indeed!

Thank you so much, Roy! I love your comment about “monster introspection.” That, of course, sounds like something of an oxymoron and yet… surely he must have had thoughts of his own!

Beautifully done, Brian. It must have been a daunting challenge to reflect Mary Shelley’s masterpiece. I think you’ve done it justice! (Great timing for me, as well, as I’m just beginning to re-read the novel.)

Thank you so much, Cynthia! Once I put myself in the shoes of the Creature I just sort of let my thoughts flow. I hope you enjoy Mary Shelley’s book, which is somewhat different in tone from the Universal Studios Frankenstein movies. Have you read about the circumstances of the creation of the novel? A ghost-story-writing contest which took place when Mary and Percy Shelley were visiting Lord Byron in Switzerland in 1816 and the weather kept them trapped indoors. What an amazing visit that must have been!

This monologue has some intensely jarring imagery, perfectly suitable to the “monster” who utters it. This is necessary for the reader, since the Frankenstein story has now become iconic, and the vision that most of us have of the “monster” demands that kind of diction. These lines are good examples:

“A raging brute who kills and pillages…”

“My smell offends me, like a butchered pig…”

“Avoid those poplars turning parchment brown…” ( I find this line frightening, for some reason)

“This incoherent brain, this ghastly face…”

Susan has already mentioned “Just grunts and strength as if I were an ox…”

But what Brian has done is also return to the original pathos of the novel, and show the interior torment of this re-animated corpse. The monster was always much more than just the lumbering beast represented in Karloff’s portrayal.

Mary Shelley was not alone in predicting the horrific consequences of a science cut loose from any human or religious anchor. Poe was haunted by the specter, as in his story “The Strange Case of Mr. Valdemar,” Hawthorne touched upon it in his tale of the scientist who attempts to remove a small birthmark from his beloved’s face (only to kill her in the process), and Stevenson created pure horror in his “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.”

Science, all by itself, is amoral, just like the natural world. And just as the natural world is “red in tooth and claw”(Tennyson’s words, I believe), so also is pure laboratory investigation and science completely cut off from ethical questions or moral imperatives.

Dr. Salemi, you have perfectly described post-modern government-funded so-called science. Humbling to know that nineteen-year-old Mary Shelley was so far ahead of the literati of our enlightened age.

You wrote “enlightened” but I think you meant “benighted.”

I concur with Mike’s comment here. It’s amazing that Mary Shelley could foresee so much of what has gone wrong with society because of science, as you describe it being “completely cut off from ethical questions or moral imperatives.”

Thank you very much for this comment, Joseph. I know Jekyll & Hyde, but not the Poe or Hawthorne works which I will now add to my reading list. You’re so right about the Karloff portrayal not depicting much of the character of the Creature. If he is simply portrayed as an automaton much of the story and its meaning are lost.

I’m pleased that you focused on the line “avoid those poplars turning parchment brown.” There is a creepiness to it for me as well, partly because I think I’m subconsciously connecting the parchment to human skin but also because of traditional tree symbolism. Linden trees described in the first line of the poem invoke marriage and happiness, both of which are out of the question for this speaker. Poplar trees reflect melancholy, death and connection to “the other world”, which this monster is not ready to face. The only exception to the Creature’s antipathy for trees is the willow tree, which symbolizes new life — even though such life is almost a cruel joke rather than resurrection. Trees also symbolize the natural order of things and, for this Creature, remind him of unwelcome, hostile people and things that he’d like to avoid.

I can’t recall the title of the Hawthorne story, even though it made a deep impression on me as a child. A scientist is bothered by a small birthmark on the face of his fiancee — a mark that looks like a “little goblin’s fist.” It becomes an obsession with him, and his fiancee agrees to allow him to remove it by some laboratory method of surgery and cautery. He works and works for hours at it, but it seems the birthmark is so deeply rooted that it reaches right into the girl’s heart. In his mad rage to eradicate the thing, he kills his fiancee.

Hawthorne’s symbolism is clear — many things in life have a profound mystery about them, and exist because of forces and designs that are beyond our comprehension. When an arrogant scientist attempts to purge the world of these things, out of sheer personal pique or annoyance, he may unwittingly destroy some precious and beloved thing whose very strangeness and mysteriousness were unrecognized gifts.

The birthmark is a perfect symbol (or objective correlative) of this truth. It is a small “fist,” that clenches and holds together the body and soul of the girl. It is a “goblin” fist, because it is connected to a world of age-old mystery that science cannot penetrate. Its roots reach down into her heart, showing that things we (in our materialist arrogance) perceive as troublesome or anomalous or unsightly may in fact have reasons and purposes unseen to us.

Isn’t this the story of amoral science today? “Destroy and eradicate everything that does not fit our ideal image of what the world should be like!”

The name of Hawthorne’s short story is, appropriately, “The Birthmark.”

https://americanliterature.com/author/nathaniel-hawthorne/short-story/the-birthmark

It’s not a very long story, quite easy to read and carries the very powerful impact that you describe with some very memorable lines. The protagonist of the story, like Frankenstein himself and like many scientists of the present, are so invested in arrogance, power-hunger and ego that they cannot see, or are indifferent to, the damage they cause. Yes, you have nailed one of the things wrong with amoral science. Too many insist on promoting their ideological (as opposed to idealistic) vision of what things should look like, twisting everything according to their own taste rather than addressing and honoring reality, with all of its mysteries.

This is a sensational poem, Brian. The Frankenstein story is such a familiar part of our culture that its easy to feel like its message has been diluted by countless cheap adaptations and parodies. Your poem recaptures the power of the original while adding a new perspective which speaks to the plight of the imperfect man caught within our current technocratic dystopia. It flows beautifully too, and despite the intricate rhyme scheme the language never feels forced. An outstanding piece of work.

Shaun, thank you so much for this very generous comment! Your own description of “the imperfect man caught within our current technocratic dystopia” is brilliant, memorable and all-too accurate.

Brian, I can feel the brute’s mental and physical pain through your vivid,

sympathetic description. Thanks for a great read.

Thank you very much, David!

Brian, this is a marvelous poem exploring some very profound concepts and questions. There are also a number of important literary allusions. I will probably make more than one comment. First, you seem to be most interested in the concept and question of the Frankenstein creature’s soul. Because the creature is alive, he must have a soul (vegetable, animal, or rational). The soul is what gives life to a body. The creature is a “damned reanimated thief,” meaning he has re-acquired an anima or soul. But is it the same soul that animated the thief who was hanged? Many of your words imply that the creature may be a mere brute, at present possessing only an animal soul. We certainly have to ask whether God, who receives and judges all human souls at death, would have allowed the executed thief’s rational and immortal human soul to return to the corpse animated by lightning in Frankenstein’s lab. When human parents procreate a human body, God holds Himself bound at that moment to create a new soul to animate the new body. He does so because the human parents are following His design for reproduction of the human species. But God would seem to be under no obligation to cooperate in Frankenstein’s work. Perhaps the corpse comes to life again as a new animal soul (which is mortal and irrational) due to electrical activity produced by the lightning.

The soul that gives life to the body is also the form of the body. I heard this explained to a group of high school students by a teacher who said we could almost see the different souls in the class just by observing the shapes of the bodies. Even identical twins who have the same DNA have slight bodily differences such as the distribution of freckles. They are different souls in these little things just as they are in the use each makes of gifts such as brainpower and talents. The Frankenstein creature poses a problem about which human soul could possibly inhabit his body, since the body was crafted by Frankenstein through altering the corpse of the hanged thief with significant parts from other dead bodies. You, Brian, make a point of the addition of hands unknown to the thief from his former life.

We have encountered this problem with organ transplants. As we have seen by experience, the transplant of a kidney or even a heart does not seem to change the personality of the receiver. He still has the same unique soul, although some grateful receivers report feeling influenced by the soul of the donor. And we see from the lives and separations of Siamese twins that there can apparently be two human souls in partially joined human bodies.

Thus the Frankenstein creature seems to have principally a soul that recognizes the body of the hanged thief as belonging to him in his previous life. But you, Brian, bring this into question by considerations of the powers of the soul. These are memory, understanding (or intellect), and will. Memories are known by the creature himself to be vanishing or incomplete, and he seems not to trust that they are truly his. His intellect is most certainly (to the reader of the poem) confused. But the will is the most important power of the soul, because it is the one in which personal moral responsibility lies. Does this creature have a human will, or merely animal instincts that hate the Transylvanian villagers just as an abused stray dog or predatory wolf would hate them? What he says about the possibility of having a wife is most significant. “She’d be just a slave bound to his will.” As a second creature of Frankenstein, she would be exactly what the speaker of the poem is, a slave without a will of his own. Love, which is an act of the will, is not possible for either of them. When Boris Karloff plays the creature as an automaton, he adopts the position that this is a will-less and soul-less being who does and thinks nothing except what Herr Frankenstein wills him to think and do. There may be little residues in the physical brain that might suggest something else, based on the prior acts of will in the reanimated corpse. But if the creature has a will, it must be Frankenstein’s. We thus get a reading of the character of Frankenstein as being the will in his creature.

Margaret, thank you for this magnificent comment which touches deeply on the subject of the soul and its relationship to the living being that it animates. You write much that is worth pondering on a subject that could easily fill several shelves full of books. Preliminarily, you are quite correct: as I suggested to Susan, my attention in this poem is very much focused on the Creature’s soul. I make this explicit in the line “Abomination! And what of my soul?” The Creature himself doesn’t know exactly who or what he is nor does he fully understand what animates him. You very methodically break it down to questions of source (God or Other?) And then you further break down the nature of the Creature’s soul by identifying three powers or aspects of the soul that my speaker addresses – memory, intellect, free will. I will respond to the latter three aspects before touching on my view regarding the soul’s source.

The Creature’s memories of his pre-death life are mostly erased, although he remembers fragments of himself as a thief and someone who was hanged in punishment. He remembers love at some level because he mourns its loss. But his memories are either gone or hopelessly corrupted. His intelligence is a bit trickier for me. He speaks in grunts – Pain! Loneliness! Grrrr! (Grrr, by the way, is a tip of the hat to Robert Browning, who used this as the opening to his Soliloquy in a Spanish Cloister,) And his logic is not particularly acute. (Cause and effect is muddled: why do the villagers hate him? How could they possibly have “made him what he is?” Why do the crimson leaves of linden trees “scream?”) The Creature is capable of thought, introspection but is also paranoid, deluded and incapable of human connection.

Then there is that question of free will. I speak of the monster’s “doom” because he is a pawn to Frankenstein’s ambitions. He has no ability or inclination to pray, he behaves in part like an automaton, in part like a wounded creature, in part like a broken (literally) man aiming for some type of dignity. Yes, he is very much in thrall to his master, the mad scientist, but there are parts of him that resist. He is a slave and yet he is no slave. He can choose to avoid the poplar lined road, he can choose which potential shelter will best serve his needs. But he cannot enter the world of men. In short, this poor Creature’s soul is just as fragmented as the body parts Frankenstein assembled to create him. A broken mosaic of a man. In the end whose soul animates him? That leads me to…

God versus Other. I fully agree with you. God is the sole dispenser of souls. Therefore, in my view, what has occurred with the Creature has nothing to do with God. Frankenstein has dared to usurp the power of God and that falls under the realm of diabolic. For the Creature it is Frankenstein who is his creator and Frankenstein has no ability to impart souls – unless, perhaps, he fragments his own soul in the making of the monster, which may be one way to resolve the discrepancy between the Creature having some free will yet also being subject to Frankenstein’s. (Rowling explores this potentiality a bit in Harry Potter.) But the nature and extent of free will in any context is fraught and, to elevate the theme, it is generally impossible to distinguish Man’s will from God’s. That is another discussion — but it has parallels here.

I don’t want to stray too far from Mary Shelley’s caveats regarding the abuses of science, but her own work begs the question: does Frankenstein (the novel, not the scientist) for all its focus on science, actually invoke the supernatural? The scientist Dr. Frankenstein certainly does not, but I think the novelist of necessity does. There’s something more at play here than mere Godless science. Science doesn’t recognize souls nor does it punish hubris. But the ruler of Hell does. In other words, there is something demonic about what happens to this “damned reanimated thief” with the emphasis on damned. A pure soul, a benevolent soul would have ascended and been beyond recall. Therefore I think this thief’s return to Earth is in some way demonically inspired through the instrumentality of an amoral mad scientist. If souls exist – and, despite her husband’s notorious atheism, Mary Shelley’s diaries indicate in no uncertain terms that she believed that they do – then there must be more than hard science involved in this lightning-powered recall of a damned soul.

These

by Waldeci Erebus

after Brian Yapko

These linden trees with falling leaves infest these ancient mounts.

They scream aloud like tran-sylvanian mobs from the towns.

These monsters spread among the landscapes of these present days,

dystopian, myopian, an opium-mad haze.

Their savage war of bloody horror and insanity

has been unleashed upon the shield of humanity.

O, Shelley, yes, that hellish situation’s now with us;

we grabbed, with little forethought, fire from Prometheus;

and all around are scattered ghoulish souls and body parts,

in this fierce Breeze, these linden leaves fall on these buried hearts.

Waldeci Erebus is a poet of darkness.

I must say, BDW, I haven’t enjoyed a comment this much in ages! Bravo on the poem and an even bigger bravo for connecting the themes of my poem to the dystopia that we face in modern times AND for explicitly invoking the original Prometheus who started the whole mess. You made my day. And I’m glad those falling linden leaves resonated with you! Thank you very much indeed!

This is many days after I said I might make another comment, but here it is at last. First, on “I thirst.” This is one of Jesus’ seven last words. Commentary on it generally says Jesus did not want water or wine as minimal comfort in His death agony; instead, He thirsted to accomplish His Father’s will by dying to save human souls. He thirsted for souls, as the creature in the above poem thirsts for his own lost soul.

Another perspective on the statement comes from anthropology. In many cultures, the dead are said to suffer thirst, which is quenched by the living pouring water on graves. This is a thirst to die completely, that is, to be dissolved, so that they can no longer haunt the living, but move on to whatever state the dead inhabit. Again, that applies to this poem, where Frankenstein’s creature abhors his state of being alive and dead at the same time.

Other interesting parallels recall the Gerasene demoniac, whose story appears in the Gospels of Mark (chapter 5) and Luke (chapter 8). His name is Legion because many devils possess him. The Frankenstein creature is like Legion in his extraordinary strength, and the ability to break chains. The villagers in Legion’s land try without success to restrain him. To avoid them, Legion inhabits burial grounds where no one will bother him. Frankenstein’s monster likewise feels tormented by Transylvanian villagers, and at the end of the above poem he wants a dark and solitary dwelling “where only dead things grow.”

The comparison suggests to me another explanation of what happened when the lightning bolt apparently brought life to Herr Frankenstein’s badly crafted corpse. It could be that demons were attracted to the evil work, and deceived people into thinking the monster was truly alive by taking possession of the body. This idea is both satisfying and problematic. The source of the apparent life is evil, and does not involve a real soul created by God, either animal or rational. But although devils can possess a living body and cause its actions, life itself may not be in their power to provide. In medieval literature, ghosts are known to come from Hell when they want something other than prayers and Masses to help them out of purgatory. Whether they ask for a bad thing like revenge, or an apparently good thing such as payment of a debt owed by the deceased, they are not to be trusted. But such apparitions are all bodiless spirits, however much they seem to be bodies animated by souls. The devils themselves can appear to living humans, or they can force condemned souls to appear, but to get control of a body, they must (with God’s permission) take one that has natural God-given life. The living victim has usually made himself susceptible through sin.

Angels, like devils who are fallen angels, do not have souls. Souls are the life force within a body, while angels are created to be pure spirits of higher intellect than bodily beings. They also have intractable will, because without a body they cannot be deceived (as we often are) through bodily senses. This is what makes their goodness superior to ours, and their wickedness much more evil: it is chosen and adhered to with full knowledge of all consequences from the beginning.

Within your poem, Brian, there are all these considerations about what is going on with the Frankenstein creature. But it seems that wayward science discussed in the story may try to explain life, without being able to create it.

Margaret, thank you for this additional, very thoughtful and thought-provoking comment! There’s much here worth pondering — especially about the nature and source of the Creature’s soul. I’m glad you recognized the simple line “I thirst” — not that I was trying to make the Creature into a Christ figure but, rather, the diametric opposite, so there’s a sort of cruel irony in his using these words. But in spite of the evil that he brings, I wanted to draw attention to the pathos of his situation. He exists on this Earth unwillingly. Is evil sometimes thrust unwillingly upon certain individuals? That free will question is relevant here. The anthropology angle you describe never occurred to me and is fascinating.

I very much like your mention of Legion and the possibility of demonic possession. In fact, though problematic, it may well be the only source of the Creature’s exceptional strength and the difficulty in effectuating that “second death.” He is clearly not simply “reanimated” — as if one could place a new battery in his neck and allow him to start working again. He is much changed from being a mere human — and it is not just because of the spare body parts. He has a malice, a strength and an indestructibility that can only be derived from supernatural means. And in this case, since God and the angels have nothing to do with it, by process of elimination it must clearly be from Hell. At least if we approach the work (novel and this poem) from the standpoint of a Western Christian point of view. And I think we necessarily must.

Thank you again, Margaret, for your attention to this poem.