.

King Dom’s Dream Kingdom

“In death’s dream kingdom…”

—T. S. Eliot, “The Hollow Me”

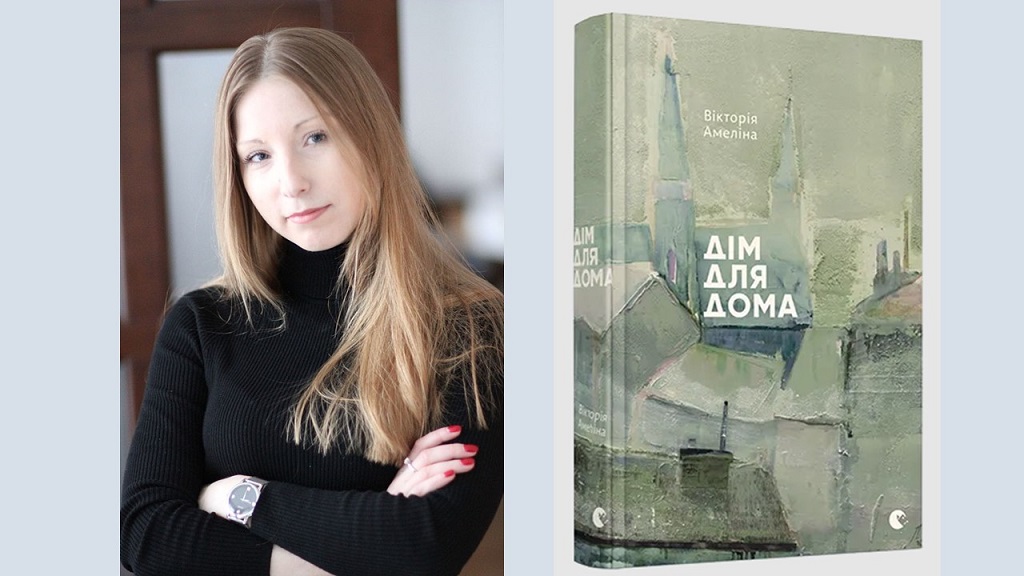

Ukrainian Victoria Amelina has died

from injuries along with others; it was dinnertime.

It happened in the city Kramatorsk, more death, more grime,

another dozen dead at th’ restaurant where they had dined.

She had been documenting Russian war crimes for a year,

her prose attempting dealing with the horror and the fear,

like as her fellow writer Vakulenko tried to do,

when he was killed in Izium in 2022,

his diary found buried underneath a cherry tree,

unchopped, like those in Chekhov’s arbour… arbitrarily.

.

.

Bruce Dale Wise is a poet and former English teacher currently residing in Texas.

The title is perfectly selected for this prose writer tying her and the book she wrote together. Apparently, she was such a young soul to be dispatched so cruelly. Adding the T.S. Eliot quote is an inspired impression befitting her death. I really like your tribute to Victoria Amelina.

As Mr. Peterson has noted, the title was tied to Victoria Amelina’s book, the T. S. Eliot tag, and as well the removed tag from Stanisław Lem. In any case, it is very difficult to achieve the right balance in a work as brief as a tennos, for the death of an individual one is not related to, as, for example, Theodore Roethke in his “Elegy For Jane”, unlike Catullus in his magnificent ten-lined farewell to his brother.

I am thankful that Mr. Peterson, who indeed has compassion for the Ukrainians, has seen what I was attempting to do; and whatever excuse I may have had for attempting this piece, I do have a deep and abiding connection both to “The Hollow Men”, and to Ukrainian literature, if mainly to its poetry.

as per Aedile Cwerbus:

Here follows the aforementioned poem by Catullus, who uses elegiac couplets, ed ist, a dactyllic hexameter followed by a dactyllic pentameter:

Multas per gentes et multa per aequora vectus

advenio has miseras, frater, ad inferias,

ut te postremo donarem munera mortis

et mutam nequiqam alloquerer cinerem.

Quandoquidem fortuna mihi tete abstulit ipsum,

heu miser indigne frater adempte mihi,

nunc tamen interea haec, prisco quae more parentum

tradita sunt tristi munere ad inferias,

accipe fraterno multum manantia fletu

atque in perpetuum, frater, ave atque vale.

Nice just-the-facts piece that digs a little deeper by referring to Vakulenko, engaged in the same type of writing. If I remember correctly, Amelina was the person who helped Vakulenko’s elderly father recover his diary wrapped in plastic and buried. She preserved his work; now we wonder if hers will be preserved. May she rest in peace.

Ms. Coats has accurately noted the “just-the-facts” quality of this work, which is what the author is striving for in his docupoetry. Of course, W. H. Auden demonstartes that extreme detachment, neatly, in the death of Icarus in “Musée des Beaux Arts”, and Randall Jarrell even more tersely in “The Death of the Ball-Turret Gunner”.

Ms. Coats likewise correctly points out the author digging a “little” deeper, noting that Vakulenko too was writing, so as not to forget recent events—ever one of poetry’s central duties—his work buried beneath a cherry tree. One does wonder what will be remembered, and how deeply it will be remembered, after an artist’s death, including, say, Anton Chekhov’s “Cherry Orchard”. That is, who will remember it? what will they remember? and how will they remember it? questions digging a bit “more” deeply, though not on a level, say, with the “remarkable” depths of Vergil.

A very touching poem on a victim of a dreadful atrocity. Amelina had already given so much.

Mr. Handley-Schachler’s comment brings up thoughts of Wilfred Owen: “My subject is war and the pity of war. The poetry is in the pity…” As such, the poem may hit a “touching” chord; for Victoria Amelina, as well as the dozen others killed in that restaurant in Kramatorsk, was a victim of a “dreadful atrocity”. And though Yeats argued that “passive suffering is not a theme for poetry”, in many ways, Owen went beyond Yeats in his poetic understanding of war.

Amelina herself was aware of the dangers there in Kramatorsk, and that she was on a list of activists to target. In that sense, she was a brave woman investigating war crimes by the invading forces, including that of Volodymyr Vakulenko, and daring to take one last trip with a group of Colombian writers to that edge of hell. And so, her death, like that of Wilfred Owen’s, does indeed strike a “touching” chord, even in a distant observer.

I agree with Morrison. It’s ten powerful lines.

The power Ms. Corey finds in the ten lines of this tennos, must come from some of its inchoate shallows and shadows, despite the starts and flaws found in it. [I know that’s how I found T. S. Eliot’s “The Hollow Men” when I first began reading it.]

The poem opens simply with the nationality and naming of the victim. [I would like her to be remembered in verse.] Note that her last name violates the meter (even in Ukrainian). However, I am always willing to break a meter when a poem’s demands require it. Early on, in my metrical poetry, I took a vow that I would not avoid words, as Vergil did with words like “arbores” or “Hercules”, if they violated the meter, which was not difficult for me to do, as my early poetry was syllabic.

The second line qualifies the first, and concludes with a terse main clause. The language here is awkward, and continues on in such a manner, taking the typical rhyme scheme of a tennos, from aabb to abba with harsh diction, chock-a-block with monosyllabics.

Lines five and six use a rather more prosaic tone, as they progress to the next part of the poem, naming a new writer, whose last name only is recorded along with the place and time of death, the final couplet drawing out one brief anecdotal fact, and pulling in one more writer’s name, the famed Russian playwright and short story writer. The poem concludes with a Dickinsonian adverb. [Elsewhere in print the poem uses the Ukrainian charichord: Radice Lebewsu.]

An excellent poem, hard to read without being refilled with outrage at what Russian rulers have being doing to everyone around them and their own for as long as anyone can remember. Thank you for stepping up.

It is nice to have new voices appear @SCP, like Mr. Dickey’s who brings his eastern European sensibilities to this site. I remember the first time I was invited to teach a class upon a poem in college; it was in a class of Semiotics @ Western Washington University in Bellingham, WA, taught back then (1982) by a Serbian-American Vladimir Miličić. We used to have intense dis-cuss-ions about poetry and language, long before any outlet opened their doors to my poetry; the first ironically an Italian-language magazine in 2010. Later, around 2017, I came upon ZiN Daily, where a poem by Serbian charichord, Béla Cedew Suri, was accepted. Unfortunately, it has been the Russian War in Ukraine that has opened up submissions for poems relating to Eastern Europe and Russia, not mainly for intrinsic merit, but rather because they have become “newsworthy”:

At a Train Station in the City

by Radice Lebewsu

“FOR THE CHILDREN”

—on a Russian rocket missile

The bodies wait to exit this war’s crematorium,

but these will not be leaving from that auditorium.

They lie upon the ground below no Tower of the Stork,

like petals fallen from a dead, black bough in Kramatorsk.

If one goes higher, one can see the Sun about to set,

Kazennyi Torets River en route to the long Donets;

and if one goes yet even higher, maybe one can see

a thousand miles away…such fine and lovely scenery.

But here they’re getting ready for the coming Russian troops,

the onslaught of the innocents continues forth, forsooth.

Radice Lebewsu is a poet fond of Ukraine. Kramatorsk is a city in Ukraine that recently had a population of around 150,000. The Ukrainian poet, whose poetic views most clearly sync and link to my own, was the neoclassicist Mikola Zerov (1890-1937).