.

Captain Francisco Menendez

Born a Mandinga, on Africa’s west coast,

Where farm and hunting toil supported most,

But tribal spats and small jihads maintained

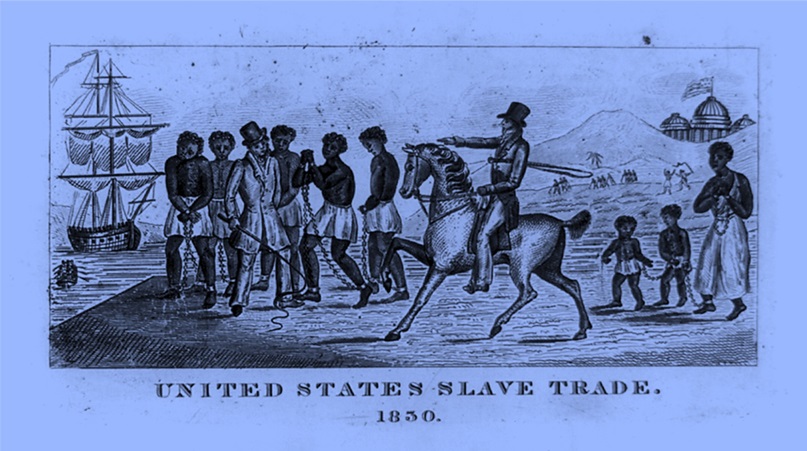

For centuries a brutal trade in slaves,

This youth was captured by some neighbor knaves

And sold and shipped to Carolina, chained.

Field labor there was harsh, conditions grim,

Yet deft of speech, he learned new tongues. To him

Came whispered words of where he might be free;

Meanwhile, he gave his slave self to a girl

And she to him, amid a rebel whirl

Of war allied with native Yamasee.

He fought so hard as to be recognized

Long after, then fled with those he energized

To seek their peace in Spain’s Saint Augustine,

Where law allowed them voices, let them buy

Or earn their freedom, and would dignify

Their industry and loyalty foreseen.

Adaptability at first required

New masters and new ways to be acquired,

New callings, and capacity to fight

In terms of musket and of cannon drill

With guns from Barcelona and Seville,

And finer crafts of how to read and write.

Appointed captain of the black militia,

He and his troopers won at last official

Establishment of outpost Fort Mosé,

A community of freedom built and governed

By men and women who themselves recovered

Nobility in sacred full array.

They promised to become the fiercest foes

To hostile realms, declaring that they chose

The Holy Faith, and Spain’s most Catholic king.

Their chief, no longer chattel but a soul,

Took on the free black township’s senior role,

Experience and knowledge broadening.

Menendez, owner then godfather, named

As kin his freedman thence to be more famed,

Intrepid champion, leader all his life,

Builder of villas, prince of slaves baptized,

And faithful to a bond late formalized:

Francisco, Ana Maria, man and wife.

Mosé was soon dubbed “Fatal” or “Bloody” when

Besieged and overwhelmed by Englishmen,

For at one daybreak its dark citizens

Surprised and slaughtered soldiers hand to hand.

They saved Saint Augustine, the Spanish grand

Castillo indebted to their diligence.

Francisco joined in harrying English ships,

Sailing by chance of war into the grip

Of enemies who mauled and re-enslaved him.

Years lost, with burnt Mosé restored, he’s found

Commander of its bustling marshy ground—

Stark challenges, however met, he braved them.

The last involved largescale diplomacy:

Homeland ceded, his trusty captaincy

Pertained to Cuba. A new Saint Augustine

Would grant to those who left behind the old

Supplies and land. Menendez, ever bold,

Moved on to freedom’s venture unforeseen.

.

.

Poet’s Note

Francisco Menendez was born about 1700 and died after 1770. He and his wife escaped from the English colony of South Carolina during or after the Yamasee War (1715–1717). He became captain of the black militia of Saint Augustine, Florida, in 1726. Still a slave, he wrote letters and petitions for freedom, and for establishment of a settlement for freedmen. Fort Mosé was founded in 1738, the year Florida’s governor formally granted freedom to slaves escaped from English colonies, in accord with Spanish royal policy proclaimed in 1693. In 1740 the Fort was overrun by English troops laying siege to Saint Augustine. The English destroyed the outpost in retaliation for their bloody rout by black inhabitants, but it was rebuilt by 1752. Menendez was captured, tortured, and sold as a slave to the Bahamas in 1741, but shows up again as free mayor of Mosé in 1759. Spain ceded Florida to England in 1763, when much of Saint Augustine’s population (including Menendez, his wife, and four children) re-located to Cuba. The Spanish crown granted Menendez a subsidy for years of loyal service.

.

.

Margaret Coats lives in California. She holds a Ph.D. in English and American Literature and Language from Harvard University. She has retired from a career of teaching literature, languages, and writing that included considerable work in homeschooling for her own family and others.

Fascinating history, which I had never heard of before, thank you Margaret. The fact that you deliver it in classical poetic format is just the icing on the cake.

The story of Francisco Menendez is truly an astounding one, even with the incomplete sources available. I’m happy for whatever sweet icing I can add.

Interesting history lesson with your usual great rhyming poetry.

Thanks, Roy. There is special military interest in it. First, in the Spanish reliance on drill to assure the most efficient use of muskets and cannons, and that black soldiers participated as equal team members. Second, that when they couldn’t use drill methods and weapons in their surprise attack on the English occupying Fort Mose, they achieved victory with bare hands. They were indeed as fierce as they’d promised to be.

Margaret, I concur with Yael — this is a fascinating history of a most improbable hero! Thank you for bringing Menendez to our attention and, from my standpoint as a new Floridian, I’m particularly pleased to learn some remarkable history about St. Augustine which readers may already know is the oldest city in the United States, founded in 1565. Is your mention of the “Castillo” a reference to the Castillo de San Marcos — the old Spanish fort which, I believe, is the oldest stone fort in the U.S. and now a national monument?

I especially enjoyed the structure of your poem with the couplet at the beginning rather than at the end. This gave the poem a sense of non-closure from stanza to stanza heightening anticipation as to what happens next in this most dramatic tale!

Brian, this poem on a great Floridian was partly inspired by my recent visit to the Castillo de San Marcos. As a native Floridian myself, it touches my heart to know Francisco Menendez came to love Florida as his country. In his departure to Cuba, the intent was to found a new community called San Agustin de Nueva Florida–but breaking ground in the Carribean wilderness was too much for a man in his 60s who had led a difficult and challenging life. He died in Havana, nonetheless a Florida hero of persevering courage and leadership.

I wanted a Spanish stanza form for the poem. The sextilla at first had six lines rhymed abbaab (rather difficult in English as medieval Romance-language forms tend to be). There are now two standard rhyme schemes, ababcc which is not particularly Spanish because it appears in English without a special name, and aabccb that I chose for this poem, lengthening the lines from octosyllables to pentameter. I like your analysis of the dramatic flow effect–and thank you for your appreciation overall.

What a great story and told so well. This would make a fantastic and inspirational movie – which is probably why it will never see the silver screen.

Thank you! There’s even a love interest here, with remarkable fidelity throughout life. Ana Maria also belonged to the Mandinga (or Mandinke) tribe, so hero and heroine may have met in childhood. But you are right, Warren, this is not Hollywood style!

As always, an education, Margaret. Now for the screenplay and the Hollywood blockbuster!

The story is cinematic in an epic picture mode, with many changes of location and turns of plot. Thank you as always, Paul, for taking time to read and comment.

Excellent narrative poem with interesting rhymes in every stanza. For further reading about slavery, I recommend “The Slave Trade”, by Hugh Thomas, which I read many years ago – covers the topic on a more global scale.

Thanks, Cheryl. The interesting rhymes come from words needed to cover a difficult topic with every line rhymed. If I were doing a fuller presentation, I’d choose blank verse. I am interested in reading more about the global slave trade, but having looked at Hugh Thomas’ table of contents, I would call his treatment comprehensive about the Atlantic trade during the four centuries covered. My interest includes Viking history, but the Vikings were no longer in business as slavers by then, and they used the Baltic or northern route to dispose of their captives. Still, while looking online at the Thomas book, I got pop-ups on English and Irish slave ports, which suggests he deals with Viking routes to some degree. And I found a horrifying statistic quoting the United Nations News of 2019. It estimated 25 million slaves in the world not many years ago! More reading seems worthwhile.

I’ll not add on to all of the commentary which addresses many of my points of praise already. I was most interested in your composition process. I loved the consideration of Spanish form and your thoughtful adaptation while searching for the right vessel for your message.

Thanks for your interest, Daniel. This was a process of composition unlike any other. I wanted the Spanish form not just because the story is one of Spanish Florida, but because Menendez was so skilled in language, and Spanish was the one he made greatest use of. His story seems a very full one, but it is characterized by lack of information at most points and by lack of resolution. He was kidnapped, escaped from slavery twice, spent much time petitioning for what seemed already due him, then went into exile, where he was not able to build as projected. All seemed to reflect the imperfect and unlucky number six, which is why I took the sextilla. Imaging incompleteness was also a reason for ending the poem where I did, rather than going on to the end of Menendez’ life. That gave a final focus on his persevering determination, which seems a better conclusion than listing and lauding accomplishments. It also completes his Floridian career.

This poem is a brief sketch, and as others have suggested above, the story could easily, with imagined plot details and emotions throughout, be a full feature dramatic action film with several sequels!

This was such an educational as well as inspirational read, Margaret! You always do such in-depth research on your topics, and it is not easy to write a historically-based poem while still maintaining a rigorous and lovely rhyme scheme. You manage to keep it poetic without making it feel like a history lesson. I especially love the lines “Meanwhile, he gave his slave self to a girl, And she to him, amid a rebel whirl.” So beautifully phrased! And creatively rhymed. How heartbreaking (in a good way!) that the two found love despite the harrowing circumstances. Thank you for sharing this meaningful story.

Christina, I’m so happy you like those words. The circumstances were harrowing, still in the Carolina plantation, and both of them slaves who didn’t own themselves to give! We don’t know how old they were, but it must have been very young. They stay together or come back together throughout their mostly undated history. Man and wife when they arrived in Florida, and when they departed for Cuba about 45 years later, with the only precise date known about either of them being December 28, 1739, the date when they formally married in the Catholic Church. Thank you for reading and commenting on this portion of the story that is dear to me as well.