.

The Convert

“Uh, Professor, I don’t get it,

Why do people choose to read that?

Does it just not fit my taste?”

She said, “If you really let it,

This will sway you. You’ll concede that

This has moved your very soul.”

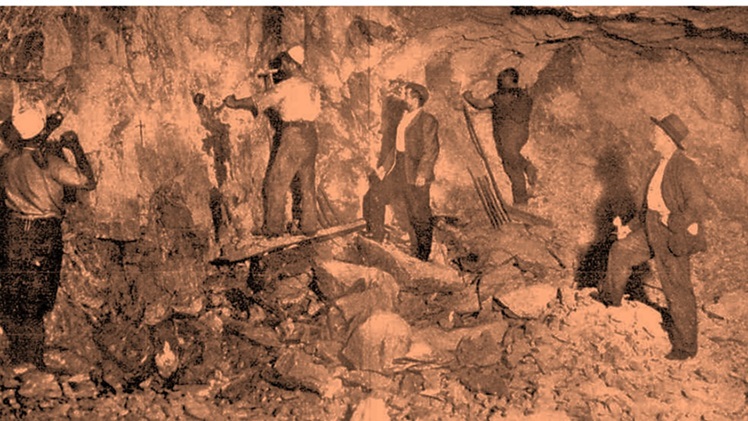

So I dug and mined each sentence,

But I simply couldn’t strike it,

Strike the value that I chased.

But, in class, in deep repentance,

I was told just why I like it,

Word for word, and now I’m whole.

.

.

Benjamin Cannicott Shavitz received his PhD in linguistics from the CUNY Graduate Center in New York City. He lives in Manhattan, NYC, where he was born and raised. He has published two collections of his own poetry (Levities and Gravities), as well as an anthology of public domain poems by New York City poets (Songs of Excelsior). His work has also been published in The Lyric. He runs two online businesses: one that teaches innovative, linguistically informed classes on language skills, including poetry writing, and one that offers dialect coaching for actors. See www.kingsfieldendeavors.com for an overview of his activities and www.kingsfieldlinguistics.com or www.phoneticsforactors.com for his businesses.

I can relate to this poem, Dr. Shavitz. I recall being of the same mind as the student in the poem, making a bona fide effort to find the meaning of a literary work that I felt had no value; and ending up humoring the professor.

The rhyme scheme a/b/c/a/b/d/e/f/c/e/f/d suits this poem well, as does the wry last line.

I sense something subversive in the conversion of the thoughts of the student.

This poem really highlights how many people can’t think freely or make up their minds for themselves and want someone to do so for them. Is it gaslighting that leads people to become sheeple, or the fear of not fitting in with what those around them believe?

Long live freedom of thought. Death to the fear of not fitting in!

Thanks for the read, Benjamin.

The nice thing about this poem is that it can be read in two ways. The clearest reading is that this is a satiric piece on classroom indoctrination, and that is certainly how I took it on first reading.

But after a few more readings, it occurred to me that it also suggests the teacher has the right to explain and analyze a text out loud to the class, and give possible insights as to what is happening in it. This is obviously the case when explaining older material to students who are young, or who may be reading such material for the first time. But you can’t just say “If you really let it, it will sway you” the way the teacher in this poem does. And yet that is typical of many modern left-liberal professors. They don’t even lecture — they just say “Read this and parrot the proper opinions about it.” That’s isn’t teaching — it’s propagandizing.

The great thing is that the poem is successful in both ways! Either interpretation is valid, and in fact they complement each other by raising the serious question as to what a teacher of literature ought to do when introducing unfamiliar or difficult texts to students. Telling the student “This is good for you — just shut up and accept it” is silly and counter-productive. But certainly the teacher should encourage the student to read with an open mind, try to understand the formal structures behind the piece, take historical context into account, and pay attention to rhetorical or grammatical tough spots. It’s here where a good teacher is indispensable.

As Mary said above, I particularly enjoyed this interesting rhyme scheme!

There is a third interpretation for this poem, related to the two Joseph Salemi has outlined. It does raise the question of how a teacher should introduce reading material, and it does satirize classroom indoctrination as silly and counterproductive. But if the reader sympathizes with student experience Mr. Shavitz describes, it’s clear that his is a poem showing how reading itself is discouraged. It does not matter whether the student reads or not. Both levels of his struggle to appreciate the text are useless. And this corresponds to another common way of getting through courses–especially ones in literature. Whatever the teacher says substitutes for student reading. Students are told important information about the work: title, author, best lines, scenes, chapters, and desirable interpretation. This is an old-fashioned method in which, a century ago, students could get a “gentleman’s C” as a grade, by picking up enough generally accepted knowledge to carry on a conversation in social circles. Today, it allows students to acquire desired attitudes of whatever “ism” the teacher professes, and look smart by applying them to famous literature. There is even a back-up bonus of boasting that one has “broken the boundaries” of other interpretations he might hear.

I favor this reading because Shavitz presents his speaker’s dilemma as an emotional one. First, he finds nothing overall to like in the text (we don’t hear whether he understands it or not). Even after diligent application, he cannot find the “value” the teacher describes in terms of emotional uplift. But at last he is told, word for word, why he likes it (or should like it). This he describes as “repentance” that makes him “whole.” Intellectual appreciation does not enter into the process. Clever presentation, Benjamin.

I like poems that say much in their brevity and this thought-provoking marvel had me hooked. Like Dr. Salemi, I interpreted the poem in the same two ways though I relate to the latter… I became “whole” long after “I was told just why I like it” by my English Literature teacher… and knew at that precise moment, he was right. Thank you, Benjamin.

A serious problem in education today is that a very large majority of students in a college classroom are simply incapable of reading any literary text, whether prose or poetry, dating earlier than 1900. The stuff might as well be composed in Gothic as far as they are concerned. This is not their fault — it is the fault of a K-12 system that has utterly given up the task of introducing students to older texts.

Margaret points out one way of alleviating this situation — the professor can simply lecture on the assigned texts, explaining their content and meaning as clearly as possible, and perhaps provoking some interest and questions from the class. This makes the professor a sort of viva voce Cliff’s Notes, but it is better than nothing, and my suspicion is that this is what most professors do now, even in graduate school.

Coincidentally, my wife and I discussed this very problem just last night, and we agreed that it stemmed from a very modern (and philistine) idea that the only important thing about a literary work was what it meant, and whether it was relevant to one’s activities, and whether it was in conformity with accepted public orthodoxies. In other words, a literary text had no more value than a roadmap that guides you to the Interstate highway.

If students are taught this lie, then there is no logical reason why they should be expected to pay attention to older texts written in antiquated language or that make use of strange rhetorical procedures. This nightmare is exactly what modernism and postmodernism wanted — the erasure of literary tradition.