.

The Trochaic Poems of Dorothy Parker

A few poets become famous, while most go down into oblivion. But a small scattering of them are eventually categorized as “minor poets,” whose work may be just as good as those who are well known, but who for some reason simply never attain the heights of Parnassus, as a professor of mine used to say.

Why this happens is anyone’s guess. Some argue that it has to do with the personal drive and ambition of an individual writer—though you may be good, it’s not enough if you don’t have that competitive fire in the belly to push your work forward, network with publishers, and gain a loyal audience. Others say that your favored subject matter may be out of sync with current fads and fancies, or that your stylistic habits are passé. And of course there are those poets who write solely for their own aesthetic satisfaction, and who have no particular interest in wide publication or celebrity.

Minor poets may survive in anthologies or on library shelves while not being part of the actively taught canon, or commented on in the critical journals of academia. They may have a few devotees, but they are not household names, or the source of easy quotation. As a result, their excellent work remains generally forgotten, unread, or disregarded.

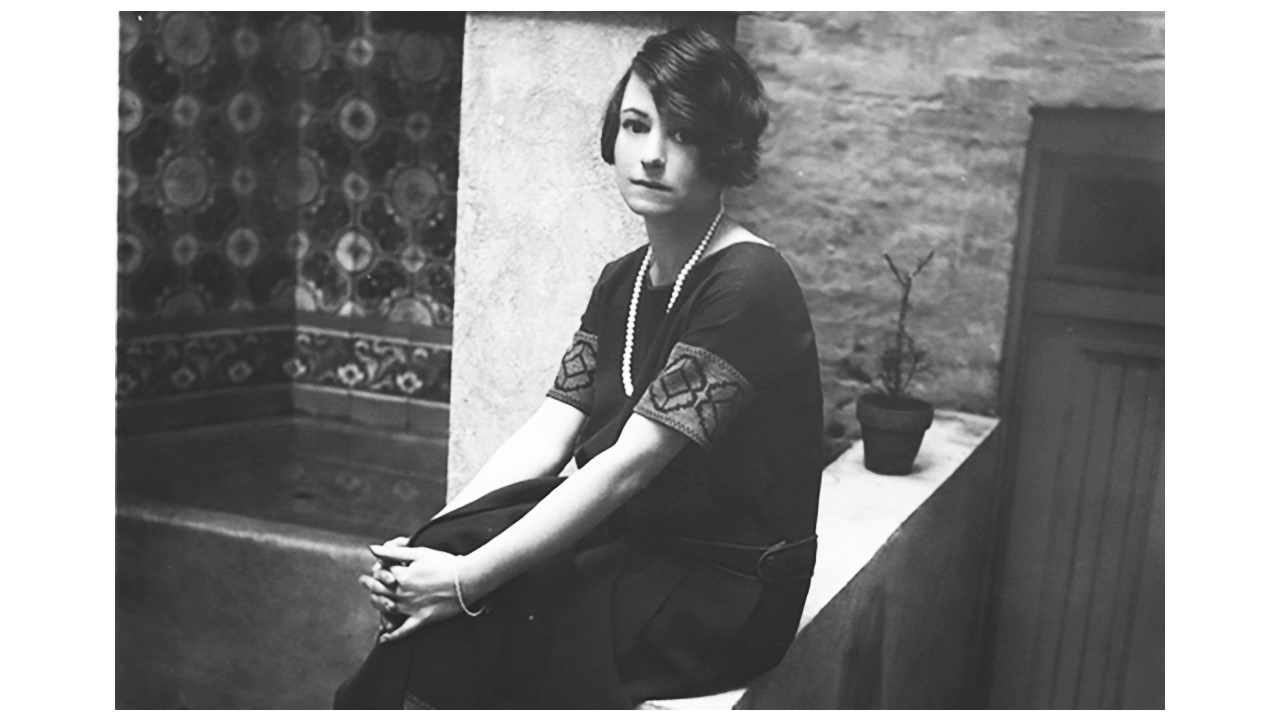

I say all this as a preliminary to my comments about Dorothy Parker (1893-1967), a poet who is definitely a minor voice, but who is still important enough to be included in a Library of America Series volume that anthologizes poets from the first half of the twentieth century. (I personally feel that Parker should have a separate volume devoted to her alone, including all of her poems, short stories, drama criticism, and commentary, but being stuck in an omnibus volume may be a price one pays for being “minor”).

Dorothy Parker published three small collections in her lifetime: Enough Rope (1926), Sunset Gun (1928), and Death and Taxes (1931). A later collection, Not So Deep as a Well (1936), contained most of the material contained in the previous three books along with some additional work. In 1944 Viking Press published The Portable Dorothy Parker, a fairly solid gathering of all her poetry and short stories. In 2009 Stuart Silverstein brought out Not Much Fun: The Lost Poems of Dorothy Parker, which gathered all of the poems that did not appear in the above-mentioned books. Most of this work was from magazines, or from manuscripts.

I have loved Dorothy Parker’s work ever since my mother read me selections from some of the lady’s facetious and impishly satirical verse. That was in 1956, when I was eight years old and had already begun to show a marked interest in poetry. I especially enjoyed those of her poems with a strong trochaic tendency. I knew little of metrical patterns at that time, but those particular compositions seemed to be forceful and memorable.

It might be best to start with one of Parker’s poems about poetry itself. Yes, yes—I know. That is a subject that lends itself to the worst sort of tedious blather. But in this case (“Fighting Words”) it is a delight:

.

Fighting Words

Say my love is easy had,

Say I’m bitten raw with pride,

Say I am too often sad—

Still behold me at your side.

Say I’m neither brave nor young,

Say I woo and coddle care,

Say the devil touched my tongue—

Still you have my heart to wear.

But say my verses do not scan,

And I get me another man!

.

This sort of work is typical of Parker at her best. It is sharp, witty, lucid, and ends with a slap in the reader’s face. The first two quatrains are perfectly trochaic, with catalexis of the last foot. But the closing couplet becomes iambic (or has a prothesis of a monosyllable at the start of each line, if you want to get fancy about it). This simple and sudden variation allows Parker to make her final point very clear, and very emphatic. And note how absolutely uncluttered the lines are; only a few figurative touches like “bitten raw with pride” or “the devil touched my tongue” decorate the commentary.

Many of Parker’s poems deal with feminine concerns: love affairs, the conflict of men and women, and appearance and clothing. Her poem “The Satin Dress” is in pure trochaic meter, and here are the first three quatrains:

.

The Satin Dress

Needle, needle, dip and dart,

__Thrusting up and down,

Where’s the man could ease a heart

__Like a satin gown?

See the stitches curve and crawl

__Round the cunning seams—

Patterns thin and sweet and small

__As a lady’s dreams.

Wantons go in bright brocade;

__Brides in organdie;

Gingham’s for the plighted maid;

__Satin’s for the free!

.

What’s wonderful about this poem is how the trochaic meter mirrors the enthusiasm and intense joy that the speaker experiences while sewing her satin dress. The rest of the poem goes on in the same style and tone, while speaking disparagingly of other fabrics and their mundane uses.

Her trochaic poem “Threnody,” which leads off the collection Enough Rope, is about disappointed love (a recurrent theme for Parker). It seems to me one of the most plangent and yet profoundly expressive statements of a broken-hearted woman who is still capable of a new romance:

.

Threnody

Lilacs blossom just as sweet

__Now my heart is shattered.

If I bowled it down the street,

__Who’s to say it mattered?

If there’s one that rode away

__What would I be missing?

Lips that taste of tears, they say,

__Are the best for kissing.

Eyes that watch the morning star

__Seem a little brighter;

Arms held out to darkness are

__Usually whiter.

Shall I bar the strolling guest,

__Bind my brow with willow,

When, they say, the empty breast

__Is the softer pillow?

That a heart falls tinkling down,

__Never think it ceases.

Every likely lad in town

__Gathers up the pieces.

If there’s one gone whistling by

__Would I let it grieve me?

Let him wonder if I lie;

__Let him half believe me.

.

In this poem Parker writes in the voice of a discarded woman, whose heart lies shattered like a glass lamp. She weeps, and her breast is hollowed with grief, but almost by second nature she is thinking of another lover in the midst of her pain. And here the trochees give the reader a perception of the speaker’s strength and resilience—their steady pounding conveys a sense of steadiness and resolve. Another lad will come along, and already the speaker is thinking about the interplay of lies and belief.

This same resilience comes out in the short trochaic poem “Pattern,” where the speaker (a disappointed woman) addresses a younger male who is trying to console her:

.

Pattern

Leave me to my lonely pillow.

Go, and take your silly posies;

Who has vowed to wear the willow

Looks a fool, tricked out in roses.

Who are you, my lad, to ease me?

Leave your pretty words unspoken.

Tinkling echoes little please me,

Now my heart is freshly broken.

Over young are you to guide me,

And your blood is slow and sleeping.

If you must, then sit beside me…

Tell me, why have I been weeping?

.

These trochaic tetrameters give a lecture-like tone to the piece, which fits in perfectly with the situation of an older woman correcting a younger man. The ending is the typical Parker twist, where all of a sudden she is no longer sad, but attracted by the young man’s attentions. But not all of her poems are about romance. Dorothy Parker was famous for her acerbic wit, her devastating put-downs, and her capacity to lash out mordantly at certain persons or subjects. Sometimes she has a general target, like the opposite sex, in the short poem “Experience”:

.

Experience

Some men break your heart in two,

Some men fawn and flatter,

Some men never look at you;

And that clears up the matter.

.

Another trochaic poem of hers is “Frustration,” one of the most savagely misanthropic pieces ever composed:

.

Frustration

If I had a shiny gun,

I could have a world of fun

Speeding bullets through the brains

Of the folk who give me pains;

Or had I some poison gas,

I could make the moments pass

Bumping off a number of

People whom I do not love.

But I have no lethal weapon—

Thus does Fate our pleasure step on!

So they still are quick and well

Who should be, by rights, in hell.

.

This is perfect trochaic tetrameter catalectic (except for lines 9 and 10), and the forceful punch that each trochee throws is the perfect structure on which to build a poem of hate. When Parker uses trochees, she is aiming for emphasis, force, and the ability to grab her readers by the throat and compel them to listen. But they are not always laced with harshness. I began this essay with a poem of hers on her own verse, and I’ll present another on that theme. The poem “Bric-A-Brac” is a sardonic self-judgment, possibly written as a way of telling the world that she had far too many troubles in life to think that her poetry was of any value:

.

Bric-A-Brac

Little things that no one needs—

Little things to joke about—

Little landscapes, done in beads.

Little morals, woven out,

Little wreaths of gilded grass,

Little brigs of whittled oak

Bottled painfully in glass;

These are made by lonely folk.

Lonely folk have lines of days

Long and faltering and thin;

Therefore—little wax bouquets,

Prayers cut upon a pin,

Little maps of pinkish lands,

Little charts of curly seas,

Little plats of linen strands,

Little verses, such as these.

.

One thing to notice in the metrics of the above poem is what happens in lines 7 and 10. Parker does something unusual with trochaic verse. The stresses in those lines are as follows:

.

BOT tled PAIN ful ly in GLASS

LONG and FAL ter ing and THIN

.

Because the words “painfully” and “faltering” are trisyllabic, Parker introduces variation into the trochaic structure. The reader does not mind, since the overall flow of the poem has already prepared him to accept a muffled stress on the normally weak fifth syllable in each line.

I’ll end by considering one of Parker’s most powerful pieces, “The Dark Girl’s Rhyme.” This trochaic poem from Enough Rope is a masterly composition of high seriousness. It has no touch of the comedy, playfulness, or sharp wit that are generally expected in this poet’s work. The poem is in the voice of a “dark girl” (perhaps black, Indian, Jewish, or of some foreign extraction) who recounts her troubled affair with a white man:

.

The Dark Girl’s Rhyme

Who was there had seen us

Wouldn’t bid him run?

Heavy lay between us

All our sires had done.

There he was, a-springing

Of a pious race,

Setting hags a-swinging

In a market-place;

Sowing turnips over

Where the poppies lay;

Looking past the clover,

Adding up the hay;

Shouting through the Spring song,

Clumping down the sod;

Toadying, in sing-song,

To a crabbèd god.

There I was, that came of

Folk of mud and flame—

I that had my name of

Them without a name.

Up and down a mountain

Streeled my silly stock;

Passing by a fountain,

Wringing at a rock;

Devil-gotten sinners,

Throwing back their heads;

Fiddling for their dinners,

Kissing for their beds.

Not a one had seen us

Wouldn’t help him flee.

Angry ran between us

Blood of him and me.

How shall I be mating

Who have looked above—

Living for a hating,

Dying of a love?

.

The first four quatrains of the poem describe the man in question: he is of a different race that is traditionally hostile or antagonistic to the speaker’s ethnic group. Quatrains 2, 3, and 4 suggest that he is a WASP of New England heritage, of Puritan traditions, and connected with farming. The following three quatrains are the speaker’s description of herself and her people, who are subordinate and self-consciously inferior to her lover’s group. By calling them “Folk of mud and flame,” the speaker is emphasizing her people’s low caste, but also their heightened passions. They are “Devil-gotten sinners” of somewhat questionable morality who fiddle for their dinners and kiss for their beds.

There is bad blood between their respective races, a hostility that goes back for years. This has complicated their relationship, and most likely been the reason for its end. But in the last quatrain the speaker expresses despair, since the experience of having an affair with a man of a higher race has spoiled her ability to accept as a mate one of her own people. The inherited hate that made her relation with a Puritanical WASP unworkable has also left her enslaved to a love that her own race cannot satisfy.

It is a powerful poem about the dangers and difficulties of interracial sex, and probably reflects Dorothy Parker’s own experience as a Jew whose lovers tended to be white Christian males. But rather than keeping the poem self-absorbed and confessional, she depersonalizes it and makes it applicable to any situation where differences in ethnic background and long-standing hatreds can destroy a love or make it impossible.

Many other Parker poems are trochaic, but there isn’t enough space to deal with all of them in this essay. Some are witty epigrammatic pieces, but others (like the brilliant “Salome’s Dancing-Lesson” and “The Lady’s Reward”) are carefully developed works that are well worth reading. I do not quote them here because they are still under copyright protection.

I hope some of our members will be tempted to compose poems in trochaic verse, as a change from iambic fives. Dorothy Parker was adept in several kinds of traditional meters, and in fact showed a preference for them over iambic pentameter. I think we can all learn from her example.

.

.

Joseph S. Salemi has published five books of poetry, and his poems, translations and scholarly articles have appeared in over one hundred publications world-wide. He is the editor of the literary magazine TRINACRIA and writes for Expansive Poetry On-line. He taught in the Department of Humanities at New York University and in the Department of Classical Languages at Hunter College.

Fascinating essay and poems regarding a person unfamiliar to me–I suppose due to the “minor poet” status. I really loved and greatly appreciated the trochaic verses that lightly tickled my tongue and enchanted my mind. I can certainly see the woman’s perspective in most of them in apposition and juxtaposition with a man’s viewpoint. Your commentary was richly rewarding and well taken while assisting me with my own perceptions of her poems. Thank you for revealing her and her poems to me. I agree we need more trochaic metered poems with such wit and wisdom.

What a delightful essay on some of the poems of Dorothy Parker. This poet has grown on me and induced me to try to imitate her–to no avail. At least I will have her work to periodically read.

Dorothy Parker’s poetry pops up quite frequently on social media sites, usually her pithier, more cutting and humorous pieces. It’s good to discover the greater breadth of her work, and I think I’m up for trying a few uniambic trochified (my poetic licence is still valid) pieces.

Thanks for an educative essay one of the more major minors, Joseph.

Thanks, Joseph, for a stimulating intro to Parker’s poetry. My parents had a collection of her writings (most likely prose) when I was growing up; too bad I didn’t have a look at it. I might have enjoyed it more than most of what I was assigned in high school.

Dorothy Parker is famous for this very concise epigram:

Men don’t make passes

At girls who wear glasses.

A couple of other thinggs, Joseph, have struck me about the works of hers that you have included here: Her lines are very direct and snappy, and she gets her point across without ever having to explain her meaning to the reader. Also, her syntax often involves ellipsed relative pronouns (such as “who”), which harks back to earlier stages of English poetry, e.g., “Where’s the man could ease a heart” and “Who was there had seen us.”

Some of her short takes are prime material for epigraphs. I remember, as an undergraduate, seeing sweatshirts that read, “You can lead a horticulture but you can’t make her think.” And consider the epigraph in the second poem of this post:

https://classicalpoets.org/2020/08/30/three-poems-on-drinking-by-c-b-anderson/

Yes, you’re quite right Kip. The ellipsed relative pronouns are typical of Parker’ style, and they make reading her poetry a smooth and easy task. And they do add an older feel to the material, as well as a kind of clipped elegance.

I have never read a line of Parker that wasn’t as polished and hard as pumice-rubbed marble. She said what she wanted to say with no dribbling blather and excess verbiage.

She was the mistress of the devastating comeback. Once at the Algonquin Circle, some catty younger woman made way for her at the entrance, saying “Age before beauty.” Parker immediately replied “Yeah — and pearls before swine.”

How many of us could think that fast?

Excellent analysis Joe. I have only encountered Parker occasionally and never possessed a whole volume by her; I shall look for one now. Those poems by her I have encountered all have that direct and bracing quality you mention.

This is an excellent essay, Joe, which offers an appreciative introduction to a poet who has not been high on my radar. I’ve heard of her, of course, and have thought of her as basically a Manhattan socialite from the 1930s who offered acid-tongued bon mots along with the appetizers. So it is a real pleasure to read some of her work and to learn more about her. At a time when insanity is prized in society, Parker’s poem “Frustration” (which you memorably describe as savagely misanthropic) certainly resonates. But her other poems are highly enjoyable, witty, pithy, clear-eyed. There’s a daring quality to her work which strikes me as the courage to speak her mind and the unwillingness to suffer fools. Parker’s ”Threnody” however is my favorite of those you’ve cited. It has an air of cynicism behind it but here it almost feels like a defense mechanism which imperfectly (by intention) masks the poet’s authentic emotional suffering. This is a poet who really knows herself.

Thank you for the introduction to Dorothy Parker. I’d heard of her but don’t recall having read her work before. And I do seem to get stuck on iambs, so this is a helpful idea.

I want to thank everyone who has commented, even those to whom have not addressed a reply. Right now at work I am inundated with student papers and exams. I appreciate all your observations.

Aside from that epigram Joe quoted in the comments, I was totally unfamiliar with her work. It is funny how many accidental circumstances go into a poet’s canonization that are independent of the quality of their work. I was playing a lego-themed video game with my nephew recently and out of nowhere the narrator started quoting a Maya Angelou poem. I thought ‘my god, is there no escape?’ Utter mediocrities are being lionized out of all proportion to their middling talent, while gems remain buried.

Thank you Professor, for a highly educational essay on one of the poets who I fell most in love with when I started reading poetry anthologies five years ago. Coincidentally, Parker enthusiast Stuart Silverstein is a friend of mine whom I’ve known since early childhood. He appreciated receiving a copy of the essay too.

Thank you so much for this excellent essay on Dorothy Parker. I know of her but haven’t read or explored much of her work and I will definitely be addressing that. I enjoy trochaic meter and a few years ago I wrote a few trochaic poems. Thank you again for the wonderful essay and indeed the prompt to “shake things up a bit” meter wise.

Joe, this is a good invitation to trochaic composing a la Parker. I have a few poems by her as well in my “database” of fair forms, showing that she was adept at considerable variety in her artistry. She may have encountered French forms in her youth, but they were definitely forbidden fashions by the time she began to publish.

The paperback “Portable” series served minor poets well. For earlier centuries (16th, 17th, 18th, 19th), I learned from the cheap Dell volumes of minor poets, usually including a dozen or so with extensive runs of pages, followed by the minimal minor poets represented by only a single poem each. These too were useful for readers who could “discover” poets suiting their tastes, and go to a library in search of more.

The Viking Portable Library series was started in 1943. It was an idea of Alexander Woollcott, who suggested it as a means of providing American servicemen with convenient and handy copies of worthwhile authors. It worked out so well that Viking continued the series after the war, and I believe there were over 70 different volumes published, both in hard cover and paperback. Other publishing houses followed suit because of Viking’s commercial success.

A lot of critics didn’t take Parker’s work seriously (one reviewer called it “flapper’s verse”). By no stretch of the imagination could Dorothy Parker be called a flapper, so I think that she was dismissed because much of her work was comic and perhaps even “light,” and was closely linked with feminine concerns. But she was an amazing wordsmith.

Joe, I hadn’t read a line of Dorothy Parker’s poetry until you made your encouraging comment on “A Half-Baked Rondeau Redoublé” – one of my winning poems in the SCP 2020 competition: “The rondeau redoublé is the best I’ve read since Dorothy Parker’s one in her book “Enough Rope.” “. Since then, I’ve been a fan.

Your delightful, informative, and beautifully written essay makes me want to pick up where the late, great Dorothy Parker left off and run with trochaic wonders until the proverbial cows come home. Thank you, Joe. Watch this space.

I’m glad I introduced you to Parker. She is shamefully unappreciated in our rotten po-biz world.

A little late to comment (and new to the Society), but I much enjoyed your essay about Parker, whom I had never read, or even heard of. I haven’t written a trochaic poem, although I have blended in lines or beginnings of lines here and there. What I love about her poetry, two things: very direct and clear (she actually says what she means, and it is not inscrutable poetry as so much drivel is today); and it is interesting, opening up her mind and personality and another view of the world (which, I think, is the only valid purpose of poetry).

Also, I think I know what you mean about minor poets, and I agree that many who are excellent are not even on the public poetryy radar. A lot probably, just as you indicated, haven’t enough drive (though often that means the stomach to endure so much bad poetry and rejections of good poetry that they give up). But I think it true, as you also said, that “Others say that your favored subject matter may be out of sync with current fads and fancies, or that your stylistic habits are passé.” I started writing poetry as a child, along with my Mother, and the inspiration was classic. Later, after becoming an English/composition teacher, I returned to it to find a world of difference. I truly hate what has become of “poetry” in the world. Imagine my delight to find this site a few years ago. But then I noticed that much of what passes for classical in form is still vapid and “inscrutible” in content, and I went away.

I thought I’d try the 2024 contest and see if I could get an airing. It may just stand out for being very different from what I’ve read mostly. Thanks for this fine essay.

Sorry for not noticing your comment until now, Mr. Crane. Thank you for your thoughtful observations on Parker, and about my essay.

You’re quite correct when you say that classical form in itself is no guarantee that a poem will be interesting or worthwhile. But this would have been true in any place or any century, and with any art form. There are millions of poor or mediocre paintings, and only a select few masterpieces. Just as there must have been plenty of lousy fresco murals in the Renaissance, and ungainly statues in Greece and Rome. So also with classical, metrical, rhyming poetry. Not all of them are successful.

However, don’t make a fetish of clarity and scrutability. There are many excellent poems that demand closer reading and attention before they reveal their full beauty and meaning. That’s why I occasionally provide notes and commentary on some of the poems I post here at the SCP — we are a teaching site, and sometimes readers and young poets may need a bit of help when a poem is more complicated than usual.