.

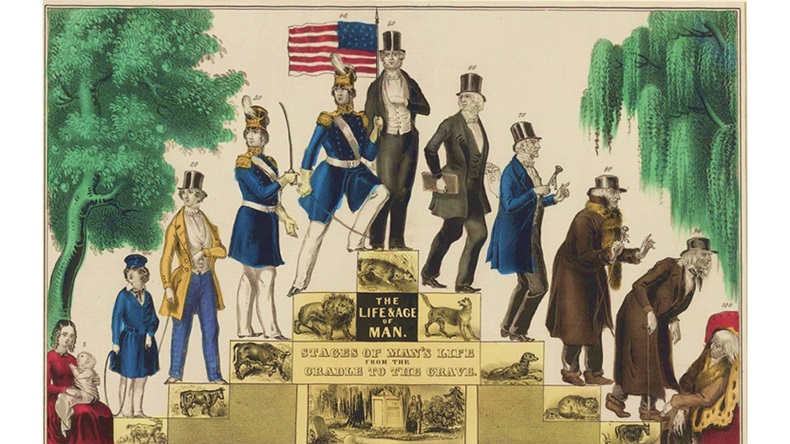

A Pleased Jaques

—after a soliloquy in Shakespeare’s As You Like It

At first there is the infant, grinning wide

because he has escaped his nurse’s arms

and her chagrin, in short shirt takes his stride

around the corner, swaggering with charms.

Next comes the busy schoolboy in the morn.

He’s running off to take his shower fast,

and then he towels off what he was born

with; clothed, back-packed, in joy goes off to class.

The lover then appears, a full-grown man,

though hairier, his moustache still is thin.

His heart pounds with delight at sighting an

exquisite, lovely beauty in the wind.

The soldier is a brave and gutsy guy,

who follows orders for his country’s need.

If necessary he will gladly die,

although it is his pref’rence not to bleed.

Then comes the man in full career form.

He makes more money than he ‘s ever made.

His eyes are cheerful and his heart is warm,

more sociable now he has made the grade.

Sixth, the old goat fits into lean blue jeans

with reading glasses on his blood-shot eyes;

but he is happy he can read a thing

and that his life is still a big surprise.

The final dude is hard of hearing, weak;

he’s slow, senile; what hair he has is gray.

Since few can hear him when he tries to speak,

he finds he doesn’t have that much to say,

content to let life’s treasures slip away.

.

.

Bruce Dale Wise is a poet and former English teacher currently residing in Texas.

This is such a touching poetic life story of the stages of living we all shall experience that is well-rhymed and flows beautifully.

as per Wilude Scabere:

“A Pleased Jaques” was a poem of fifteen years ago. Through the melancholic character Jaques, Shakespeare, in his noted monologue “All the world’s a stage…”, divided life into seven ages, from infancy to old age. I was interested in taking Shakespeare’s lines of blank verse, dividing them into quatrains with monosyllabic rhymes, and then reversing the attitude. Though it might not have been touching, nor flowing beautifully, I did enjoy the challenge.

There’s much to be said for a positive attitude, Bruce. Your ending lines sum up the refurbished soliloquy happily: instead of being sourly “sans everything,” the old dude is “content to let life’s treasures slip away.” And this aptly generalizes the just mentioned difficulty of not being heard, by positing a pleasant lack of much to say. Dare I call this genuine inspiration?

Aurelius Clemens Prudentius

by Aedile Cwerbus

Aurelius Clemens Prudentius was born in Spain,

a late 4th century Christ-follower and zealous man.

His early years were filled with sorrow, under blows of rods,

yet later, when the toga dyed his words, they were not God’s.

Lascivious, indulgent lust, as well befouled his youth,

and galling shame then plagued him; he was so far from the Truth.

Next came his stubborn animosity, which bore hard fruits;

though served him well in governance and various disputes.

At last, advanced from soldier’s ranks, he joined the emperor;

renouncing vanities, he tempered errors prudently.

Devoted to God’s glory, and His martyrs, he wrote hymns,

that still sustain his memory since when his flesh left him.

Aedile Cwerbus is a poet of Ancient Roma. Margaret Coats is a contemporary NewMillennial poet.

Gratias ago, Aedile Cwerbus. I suppose that your surname is of the fourth declension rather than the second. You have noted the similarity of theme between Bruce Dale Wise’s adaptation of Shakespeare and my translation of Prudentius, then rendered Prudentius in Mr. Wise’s characteristic iambic heptameter. I value the honor done Prudentius and myself! I hope you will not object to my copying your rendition at my post, where it will surely be of interest.

per Aedile Cwerbus:

by all means

Thanks, Bruce. Will do.

as per Lew Icarus Bede:

On Books That Shaped My Art

Some decades ago I came across an essay by contemporary poet Daniel Bourne, which was a list of ten works that would be on his bookshelf. It is his story of how he came to poetry. It included a novel, Tolstoy’s War and Peace, poetry books, like Baudelaire’s Les Fleur du mal, The History of Polish Literature by Czeslaw Milosz, and an unopened package of pencils from the Thoreau pencil company. I liked it because it said a lot about him and his poetry; and I thought it would be a good challenge for me as well to take an overview of works that have inspired me, though none might care to read it.

1. To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee. The first work that captivated me, a novel, was a one hit wonder, like Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights, that sent shivers up and down my spine when I first read it as a teenager. It was an introduction to the world at large, in particular, one tiny piece of it—the South. It made me drop everything I was working on—a college education at the time—and think about what was on its pages. It made me think that reading really mattered. I know I didn’t understand Lee’s many insights into humanity, when I first read it, nor how far beyond ethnic sensibilities it delved, nor could I have neatly catalogued it as a Postmodern Huckleberry Finn, like Catcher in the Rye; but there was enough within it, to sustain my interest back then. I don’t claim for it a place, like Tolstoy’s War and Peace, after whose character Andrei, I took as my name, when I lived in Russian House at the University of Washington, nor Melville’s extravagant Moby Dick, Dostoevsky’s breathtaking Brothers Karamazov, and many other novels of comparable vision, including that most extraordinary novel of ideals and realities Cervantes’ Don Quixote; nor do I claim for Lee a fertility of characterization the equal of Charles Dickens, nor the linguistic textures of Hawthorne, George Eliot, or Henry James. Yet, still I admire her style that quietly encompasses the understatement of Hemingway, the intensity of Faulkner, and the poetic acuteness of Flannery O’Connor.

2. The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. Although listed second, the poetry and plays of Shakespeare have had the greatest influence on me over the years. Hamlet, unsurprisingly, figures prominently. What is there not to impress about its architecture and its language, its humour and its horror? But I have admired the magic of Love’s Labour’s Lost, Much Ado About Nothing, As You Like It, and Twelfth Night. And too, the passions throughout Romeo and Juliet and its counterbalance The Merchant of Venice, the Roman plays, like Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra, the histories, like Richard III, Richard II, Henry IV, parts one and two, and Henry V. Not all the plays have caught my fancy, but others I admire include Othello, Macbeth, Coriolanus, Troilus and Cressida, The Winter’s Tale, Cymbeline and The Tempest. I know I have been influenced by others I have not mentioned; but, like the sonnets and the poems, not all have equally impressed me. Here is a sonnet on one of his plays.

On a Play of Shakespeare’s

by Wilude Scabere

Tennyson died with a copy of it

in his hand—Cymbeline, the Celtic King!

In his brief life, John Keats, too, did love it—

and lovely heroine, sweet Imogen.

That horrid world, entwined with beauty’s truth,

filled with the gross and strangest loveliness,

is rude, baroque, ornate, grotesque, uncouth,

filled with deceit, pure hearts and ugliness.

One is repelled both by its violence

and death; and yet, redemption is there too,

along with hopeful peace and innocence,

and glimmers of a spirit coming through.

It is an odd and awful winter morn

into which, far off, Jesus Christ is borne.

If Shakespeare’s language lacked the strength of Aeschylus and the fluidity of Sophocles; still he is for me the most profound influence on my poetic practice. I cannot even think how my poetry would have developed were it not for the remarkable subtlety of his language. No writer has had a greater influence on my writing.

3. T. S. Eliot’s criticism and poetry. The most important Modernist upon my poetic practice has been T. S. Eliot. Here is a sonnet on his life, he who never wrote sonnets.

Words Written April 15, 2010

by B. S. Eliud Acrewe

In the end, he became a Royalist,

an Anglican and true-blue Englishman;

for they defined for him what loyal is

enroute to being a poetic shaman—

Thomas Sternes Eliot—who, like Mark Twain,

was born upon the Mississippi, but

fled to Harvard, the Sorbonne, and London,

where he banked, friend of the Pound, and published.

A subject by 1927,

he wrote verse, essays, and plays, and received

the Nobel Prize for Literature in

the year of 1948—the thief…

of personality, he met life’s test,

restrained, remote, austere, and self-possessed.

In the same way that I have fought with Shakespeare’s poetic works, so too did I struggle hard against the work of T. S. Eliot in my early years. Although those battles, like those with other American Modernists, like Williams, Cummings, Crane, Moore, and Stevens, inter alia, have faded into the background, I still respond with enthusiasm to Eliot’s prosaic insights. When I was young, I particularly enjoyed his fragmentary, montage, cut-and-paste techniques, like those of Pound, Pessoa and Dos Passos, and his dramatic monologues, like those of Tennyson, Browning and Pound. Obviously, part of Eliot’s power came from Pound’s practice. But over time Eliot’s poetry’s fragmentary quality began to wear thin, whereas his literary essays continued to impress. To return to them is like returning to old friends. One thought of his, which I have always felt a bit extreme, but which has nevertheless been a spur on my poetic practice, was his comment that “Dante and Shakespeare divide the modern world between them; there is no third.”

4. Dante’s Divina Commedia. A fourth important and early influence on my work was that of Dante in his Divine Comedy. Three major things I drew from Dante’s poetry were its elasticity, which has always made it seem, the most modern of all writing—no matter when I read it, its terza rima and architectonic structure, which I adopted in my bildings, and in my juvenile micro-epic Roma, and his recognition of the importance of Vergil. I love and admire Dante’s Medieval Encylopaedism, his visionary facility, his frankly confessional attitudes, and the purity of his lines, which even to this day continue to impress. In light of that here is a sonnet, whose rhyme scheme is modeled on a sonnet of Dante’s.

To Dante

by Buceli da Werse

Dante, I wish that Vergil, you, and I

could stroll across this grand world endlessly,

century after airy century,

taking in all that lies between the sky

and turning Earth, contemplating the why,

wherefore, and how of life’s great tapestry,

from Tuscany unto eternity,

from the fish that swim to the birds that fly,

so we could create sweeter, newer styles,

Renaissances, every so often, when

the whim comes upon us, or a gust blows

us to a new beginning on one more close,

taking notes on all that we happen on

and sending them to Homer, Happy Isles.

5. Various Classical and Romantic German composers and literary figures. My twenties ended with two years stationed in Heilbronn, Germany, where I fell under the spell of many 18th and 19th century Germans: in poetry, Goethe, Hölderlin, Heine and Hesse, in music, Bach, Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, in math, Leibniz, Euler, Gauss and Riemann, and in philosophy, Nietzsche. I admired Goethe’s vision, Hölderlin’s intensity, and Heine’s ironic lyrics; and, like so many following after, I was overwhelmed by Nietzsche’s power. In time, the hold of German literature has loosened; but I continue to feel that the German approach to Ancient Greece is the most productive, which strikes me oddly, as German is such a consonant-cluster-thick language.

6. Ancient Greek Poetry and Philosophy. As I moved into my thirties, the German attitude to Ancient Greece brought me to the Classical World of Homer’s enormous achievement in epic poetry, however largely he participated in it, the Odyssey and the Iliad, two works whose estimation by me has only increased with time. I stand in awe of their artistry. Granted, I look on them with a more critical eye than I once did, as I do all literature, but for me they remain the twin pinnacles of the kind of writing toward which all poets should aspire. I think Pope, the great English critic, puts it best in English in An Essay on Criticism when he writes:

When first young Maro in his boundless mind

A work t’ outlast immortal Rome designed,

Perhaps he seem’d above the critic’s law,

And but from Nature’s fountains scorn’d to draw:

But when t’ examine ev’ry part he came,

Nature and Homer were, he found the same.

Convinc’d, amaz’d, he checks the bold design,

And rules as strict he labour’d work confine,

As if the Stagirite o’erlooked each line.

Learn hence for ancient rules a just esteem;

To copy nature is to copy them.

As a note, I do not think T. S. Eliot wrote a single critical essay that compares with Pope’s brilliant, youthful oeuvre, An Essay on Criticism. In addition, there were other Ancient Greek writers who also inspired me, the two foremost, Pindar, in his poetic flights and Aristotle (the Stagirite), in his incredible philosophy. The latter’s remarkable philosophical stance is one toward which I believe all philosophy should strive. Nor am I denigrating the great dramatic philosophy of Plato, the great dramatists of Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes, Euclid’s The Elements, nor many other great Greek writers of the ancient world; I am only demarcating those figures whose works most informed my own poetry at that time.

7. Vergil’s Aeneid. It is Vergil, Maro, as Pope notes, who sets the bar highest in literary achievement. He is the great epic writer of compression; he is my classic. And though his work remained incomplete at his death, like other great works of literature, Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales and Spenser’s Faerie Queene, still there is the odd quality about its power that makes it seem complete, even beyond the minimal work of Augustus’ assigned executors. Although I may have learned more from Shakespeare about my language, I have learned more about how to write from Vergil. It’s not that I don’t see his many flaws, as my own too are so obviously pronounced; even among his relative contemporaries, he lacks the variety and humanity of Horace, the polish of Ovid, and the oratorial skills of Caesar and Cicero. But despite all of that, there is still the enormity of his enterprise, which casts its incredible and powerful net over John Milton in his panoramic Paradise Lost, Dante in his Divina Commedia, and me in all my work.

8. Art books. From my thirties on, painting has occupied my mind, particularly the Italians, and that classic moment that coincides with the works of Da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael. In the same way that no one work of literature completely inspires me, so it is true of painting; but I have for some time been struck by the extraordinary artistic vision of the great Renaissance Italian painters. I have written hundreds of ekphrastic poems; paintings have inspired countless works of mine, and many better than section 4. from Five Glimpses of Four Women and a Man, in a work on Da Vinci portraits of women; in the form of a bilding [sic], its structure my answer to the Italian sonnet. Here are 144 syllables on La Gioconda:

La Gioconda

by Buceli da Werse

Her eyes on the horizon, soft, brown, look upon

the viewer from wherever he or she may be,

her head to chest, a golden section finely drawn

to match the half-length portraiture of the lady

who sits upon an armchair near a parapet,

her right hand resting on her left arm. The hazy

background’s warm, earth tones hovering around her breast

and cooling to the blues and greens and white around

her head, her long hair falling in an airy net.

What is there not in Mona Lisa to astound?

La Gioconda’s smile? the subtly ranging tones?

the human frame’s perfectibility unbound?

Even more so than the great romances of Renaissance Italy, Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso and Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata, or the mathematical works of Niccolò Fontana or Cardano, have the painters and sculptors of Italy informed my art, like Giotto, Fra Angelico, Masacchio, Uccelo, Francesca, Montegna, Giogione, Titian, Cellini, Caravaggio, and Canaletto, inter alia. And though the brilliance of the Italians in art can hardly be equaled, how many others have I not also looked at ekphrastically? like Dürer, Bruegel, El Greco, Poussin, Rubens, Velasquez, Rembrandt, Watteau, David, Turner, Constable, Friedrich, Blake, Rosetti, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Seurat, Picasso, and Americans, like Homer, Sargent, Eakins, Hopper, Wyeth, and Lichtenstein.

9. Bertrand Russell’s A History of Western Philosophy. A work that informed my mind more than it did my writing was Russell’s History. History has been a favorite topic of mine, since my teenage years. In high school my favorite class was World History, and I have always been imbued with its principles. I have frequently felt like Vergil’s Aeneas, carrying Anchises and guiding Ascanius. I look at so many things historically, it is surprising that I do not write history. It is true that such an interest explains my own interest in writers like Vergil, Pope and T. S. Eliot. Throughout his book, I enjoy Russell’s petty remarks, like those that target Leibniz, a greater mathematician and logician, as much as I like his occasional insights. In my thirties, I read and reread its various parts as the moment struck me. Although not as exciting as Wittgenstein, nor as enjoyable as Santayana, nor as obtuse as Charles Sanders Peirce, I still like its condensation and clarity of presentation, and for a while I thought he was the great mathematical philosopher of our time. In mathematics, however, it was Carl B. Boyer’s A History of Mathematics that accompanied me on my intellectual pursuits.

10. Now, as Daniel Bourne ended his list with a Thoreau company pencil box, I would like to end my list with my own box of miscellaneous writers whose works have informed my writing. Each of the following writers has coloured my own writing, sometimes in ways that are difficult for me to disentangle:

a. the Hebrew writers;

b. the Greek Gospel writers Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, and Paul’s epistles;

c. Tang Chinese poets Du Fu, Li Bo, and Wang Wei;

d. Japanese anthologies Man’yoshu, Kokinshu, and Shinkokinshu;

e. Japanese haiku writers Basho, Buson, Issa, and Shiki;

f. the Spanish mystics, like San Juan de la Cruz;

g. Spanish Mannerist Luis de Góngora;

h. French classicists, including mathematicians, like Descartes and Pascal;

i. French Parnassian Stéphane Mallarmé;

j. Russian poets Pushkin, Lermontov, and Tyuchev;

k. the British Romantics, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shelley, Keats, and Byron;

l. Poetic outcasts, like Edgar Poe, Emily Dickinson, and Gerard Hopkins;

m. British satirists Jonathan Swift and George Orwell;

n. Argentine sonneteer Jorge Luis Borges;

o. and Postmodernist poet Robert Lowell.

As in my twenties, when I created new poetic forms, like the bilding [sic] etc., in the NewMillennium I have shifted from iambic pentameters as in “A Pleased Jaques” or syllabic hexameters, as in La Gioconda, to an iambic heptameter line, as in tennos, dodecas, etc. from our nativist tradition, as in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Rime, as in the following poem from 2017.

High-minded Elevants and Asstronuts

by Brice U. Lawseed

“…all true believers break their eggheads at the convenient end.”

—paraphrase of Reldresal, in Gulliver’s Travels, Jonathan Swift

For some time, there have been two fighting factions in this land.

They’re called the Elevants and Asstronuts, you understand.

They are distinguished by what they have soaring in their minds;

and both are sure they have the highest thoughts one can opine.

The animosities between these parties run so high;

at times one can discover their ideas in the sky.

They vex each other so, they will not eat, nor drink, nor talk

together, and would rather undergo electroshock.

And in the midst of these superlative, high-flying piques,

they both are threatened by exploding, rocket-riding freaks.

Here in the NewMillennium I have flushed out my experience and understanding of so many of the millions of writers on planet Earth. The longest poem I have attained using the tennos stanza is the 450-line Coronal written in 2020. In that work, I achieved new vistas, but as it has not met with any interest (like so much of my poetry, in general), I have concentrated on what I can condense in tennos, dodecas, and other similar structures. Perhaps after my life there will be an audience for my poetry and what I have been striving for during these PostModernist and NewMillennial eras. Perhaps not. And yet, it still would have been worth it…after all.

Have finally had time to read this, Bruce. Quite a library! I like your included poems, especially those for Shakespeare, Dante, and La Gioconda. I notice that Alexander Pope receives praise in two of the numbered slots, without himself being directly named in any. But that is, of course, a unique means of being both included and quoted. I may try this “top ten” exercise someday, or use the Japanese method of claiming to give 100 items, while always making it 100 plus a few. Your actual count would exceed that number. But if it has to be ten, I’ll share Shakespeare and Vergil with you.

as per Lew Icarus Bede:

The above essay and poems were more of a focus ten to twenty years ago, as was “A Pleased Jaques”. As we begin the next quarter century (2025-2050), as you noted, I am empha-sizing structures, like the tennos and the dodeca. Iambic heptameter couplets are a satisfying form for me, for their openness and simultaneously their brevity.

I was also happy that you took my plagiarism playfully (not as it were, a pla-gue); for that is, I think, one of the greatest attributes of Shakespeare’s, the envelopment of another writer’s words. It is an homage to one of the best critical figures of our era: Margaret Coats.