.

Last Words

They say I traced my finger in the air

Before I died and let the wind erase

My final, silent words. Those who were there

Had fixed their eyes upon my dying face

But found they were unable to agree

On whether I had died in peace or not.

The closest members of my family

Believed that in my face they each had caught

A glimpse of mirth paired with a whispered sigh

Before I passed away. But others said

The way my eyebrows turned suggested I

Had died in pain and suffering instead.

I won’t say either one was right or wrong

For neither whimsy nor discomfort crossed

My mind as dying carried me along

And bid me pay in full the final cost

Of interest due on life’s mortality.

But in surrendering my final breath

And trading this world for eternity,

I left a blessing ere I entered death.

Above my bed, in my distinctive scrawl,

I wrote the words, “Be good!” And all the while,

In looking back—as far as I recall—

I may indeed have also left a smile.

.

.

James A. Tweedie is a retired pastor living in Long Beach, Washington. He has written and published six novels, one collection of short stories, and three collections of poetry including Mostly Sonnets, all with Dunecrest Press. His poems have been published nationally and internationally in The Lyric, Poetry Salzburg (Austria) Review, California Quarterly, Asses of Parnassus, Lighten Up Online, Better than Starbucks, Dwell Time, Light, Deronda Review, The Road Not Taken, Fevers of the Mind, Sparks of Calliope, Dancing Poetry, WestWard Quarterly, Society of Classical Poets, and The Chained Muse. He was honored with being chosen as the winner of the 2021 SCP International Poetry Competition.

This is splendidly paced, Jim. The enjambement not letting the rhyme make the progress stutter. It flows so smooth from the beginning that its ease may be a giveaway of how things will end in this speaking out about death.

Interesting the way the speaker talks of the immediate afterwards and speculates on others’ understandings of his own demise.

And of course, the very tying-things-up in the wise directive, or order, of “Be good!”. And why not ? It seems the best thing to do (or try for) !

Dear James,

After such a somber topic, you still managed to end on a high, positive, note. Beautifully conceived and written.

Tonia Kalouria

These are fine quatrains, with excellent masculine end-rhymes, and there is good enjambment that carries over from one quatrain to another in three places. That kind of linkage is a solid asset when putting narrative into discrete quatrains.

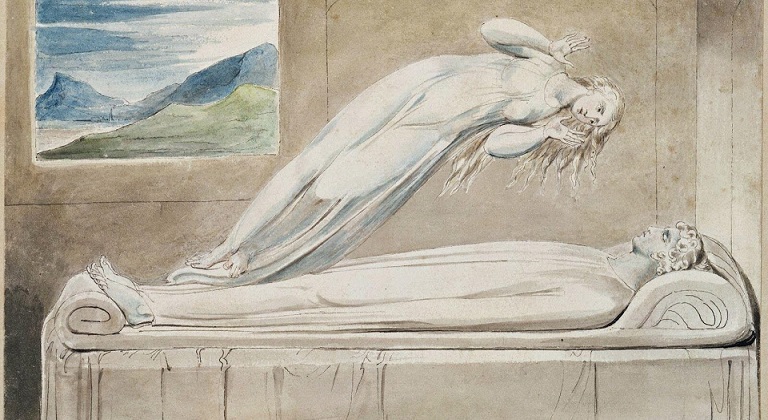

About the illustration — Blake used this same composition in another engraving, showing a triumphant and bearded masculine figure arising from a dying man, with mourners at the bedside. In the one here, the soul is imagined as a feminine figure. As a spiritual being the soul can have no sex, but it is necessary for an artist to depict the soul in a shape that is recognizable to us.

I find this poem graceful and thought-provoking, and the illustration by Blake, one of my favorite artist/poets, has the same otherworldly quality the poem contains.

With this poem, James, in my opinion you have carved a niche for yourself in the canon of metaphysical poetry, which, at its best, is the kind of poetry I most enjoy reading. As is often the case with your poems, this one comes across as a doctoral dissertation on the subject of Moral Philosophy. Please don’t be in any hurry to leave us, because we need you now more than ever.

This is a wonderful story of a soul conscious of his birth into eternity. I love the next-to-last line reflecting the unimportance of earthly life to the newly fledged heavenly being.

As the higher part of a person, human souls certainly do possess sex throughout their eternal existence, including the time between death and resurrection. Angels are the sexless spiritual beings. The prodigious gift of human sexuality involves every aspect of the person, not just reproductive organs or even the gender-coded DNA in every cell of the body animated by the soul which is the body’s form. It is neglectful of the riches of human personality to suppose that the saints in heaven are temporarily neither male nor female.

The soul leaving a human body is sometimes represented in art by a bird to suggest free motion of the spirit. It can also be pictured as a miniature living figure of the deceased individual. But it is common in art and in literature to represent the soul of either a man or a woman as female, as in the illustration above. The reason is that the soul, in relation to God, must acknowledge itself as inferior and submissive, just as women in most traditional human societies are the weaker sex, directed and protected by men. This is a countercultural idea today, and indeed men have often been uncomfortable with such representations of men’s souls as female, and with the idea of necessary personal submission to the Creator as a woman submits to a man.

Thanks for the read, James, and…be good.

Re the Blake engraving.

This one of twelve Blake drawings created to illustrate a printing of Robert Blair’s poem, “The Grave.” (1808) Blake was cheated out of doing the actual engravings which were done by Luigi Schiavonetti (who was paid many times more than the pittance Blake received). Of the twelve illustrations five explicitly depict the human soul—all five being the soul of various male persons. Three of them depict the soul as a female and two, including the one cited by Dr. Salemi, are depicted as male. The feminine representations no doubt derive from the fact that the word for soul in Hebrew (nephesh), Greek (psuche), and Latin (anima) are all feminine nouns. This has generated much speculative philosophying, theologizing, and psychonalysing (especially Jung) that leads us to nowhere in particular, akin to pulling spiritualized rabbits (or whatever else we want to extract from a grammatical quirk) out of a hat. Blake’s own ideas, while firmly grounded on a biblical/Christian foundation, are untethered to any creed, doctrine or catechism created by any established church. Rather, Blake’s spiritual views were drawn from personal visions which were, to say the least, to our eyes idiosyncratic and—aside from what Blake himself wrote about them—beyond our ability to fully understand, interpret, or otherwise make sense of. We do both ourselves and Blake no favors by trying to read too much into them. Both Blake’s poetry and the images represented in his art are simply what they are and, personally, I can find no evidence of anything resembling a systematic theology behind any of of it, despite the interminable attempts of aspiring doctoral students to do so.

A good and simple introduction to the cited illustrations to Blair’s poem can be found here:

https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/collection/international/print/b/blake/grave.html

James, the story that your speaker traced words in the air as he was dying recalls Christ tracing words in the sand during the incident of the woman caught in adultery. We never find out what those words were, although at the end of that incident, He tells the woman, “Go and sin no more.” When your speaker says his “final, silent words,” erased by the wind, were “Be good,” that is the positively expressed equivalent. We can thus imagine the speaker as a disciple of Christ, and possibly a pastor such as yourself, leaving his most important legacy.

In regard to artistic representation of the departing soul in Blake’s work, his pictures of female souls for male persons are not based on grammar of the sacred languages alone. They follow a very long tradition concerning God’s marriage to the soul, abundantly based on Scriptural passages (Hosea, Isaiah, Ezechiel, all the Gospels, Romans, Corinthians, Ephesians, Apocalypse). We could add Song of Songs. Although some interpreters see only human love there, many more go on to see both the individual soul and the faithful community (Israel or the Church) in love with God or sought by His love. Blake’s own visions were undoubtedly informed by the Biblical image of God as bridegroom or spouse of the soul, with no need for a creed or catechism to confirm it. In fact, the image is more likely to appear in prayers that he might have heard, and in theology that he didn’t read, than in a creed or catechism! As for his visions being idiosyncratic, those go on to build up literary and artistic traditions nonetheless. Representations of the departing soul as a bird undoubtedly gained impetus from Saint Benedict’s vision of his sister’s soul departing as a dove (implying her holiness in relation to the Biblical image of the Holy Spirit).

Before we try to re-imagine Blake as connected to orthodox scriptural religion, we should remember that his strongest fictive depiction of what we would call “God” is Urizen, the tormented lawgiver whose need to dictate and control the universe causes grief and suffering. Remember one of his Proverbs of Hell: “Prisons are built with stones of Law; brothels with bricks of Religion.” Any kind of overarching law-giving authority was anathema to Blake.

I agree with James that we can attribute to Blake a Biblical foundation untethered by any creed. We can also say that he exhibits varied phenomena known from the anthropology of religion. God’s marriage to the soul has analogies in Dionysus and the Maenads.

As well as Zeus’ rape of a wide range of women.

James, this is a poem to remember, both for its uplifting description of death, and the enjambment enabling effortless narrative flow.

Thanks for your thoughtful poem.

Well! Love the poem; love the debates. I don’t know if I have ever read a pleasant death poem before, so that in itself is a victory not to be missed. On the roller-coaster of life, we are easily distracted into forgetting the ride is secure.

The mourners felt not unlike Job’s friends — well intended, but… you know…. I like the resolution, indicating to me that this poem might have incubated mentally for a while before finding the page, the mind of the dying man in just the right place for all to be a little bit right. Most importantly, what I like is that the poem *shows* it’s gonna be alright, it never tells us.

My peanut-gallery contributions are these:

1. A note that the story of Jesus writing in the sand is very strongly attested as not belonging in the Gospel of John; however, I mean “doesn’t belong” in a different way than the scholars thus far have meant. Last year I was exposed to a lecture on the masterful, mind-blowingly masterful literary qualities of The Gospel of John. (Tim Mackie) I think the story of the adulteress is like one of those great lines or sections you have for a poem, but it just doesn’t fit the overall architecture and you have to kill your darling, as it were. But I believe the story true and in its swatch, beautiful on it’s own. No one could bear to lose it though.

Regarding Blake (and his un?conscious kinship to the Gnostics) and Zeus and all that, I’d have to say that I’m more than a little persuaded by Milton’s view of the ancient myths. Not sure I’m all the way there, but his thought was that they were the guises and amusements of the devil and his followers.

Oh, final thought: One last weirdness. I was reminded, at least on a surface level, of Beethoven’s death, where he is said to have raised a fist into the air at a final crack of thunder… interpretations abound…