.

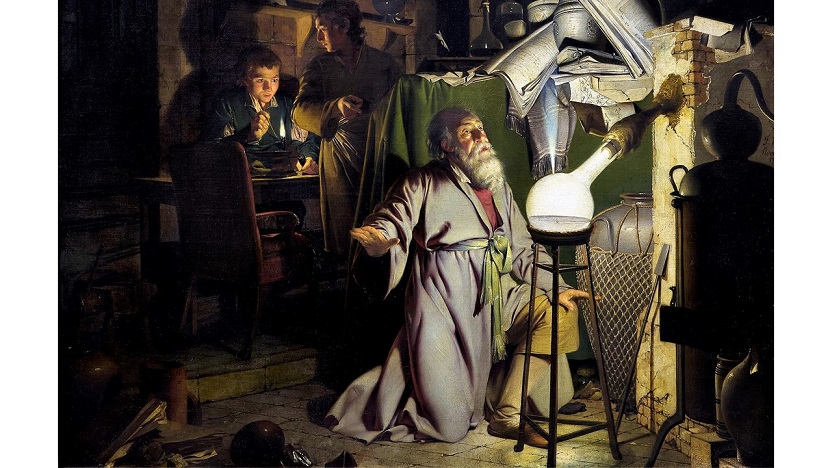

Poetry As The Philosophers’ Stone

The alchemical art, though long in disrepute, is nevertheless of great antiquity. Supposedly founded by Hermes Trismegistus, a Ptolemaic Greek reflex of the Egyptian god Thoth, alchemy has fascinated men since the days of imperial Rome, and probably earlier. Thinkers as diverse as Albert the Great, Marsiho Ficino, and Isaac Newton took it seriously.

The aim of alchemy was the production of the Philosophers’ Stone. This rare thing was said to be a lustrous red mineral with an unearthly fragrance, attained by the alchemist only after painstaking labor and trouble. But once in possession of the stone he could use it to transmute base metals into gold, and the effort was therefore worthwhile. Of course, a great many avaricious persons dabbled in alchemy out of sheer greed, and numerous con-men professed the art solely to defraud the gullible. The best examples in English literature dealing with the phenomenon are Chaucer’s The Canon’s Yeoman’s Tale, and Ben Jonson’s still-hilarious comedy The Alchemist.

However, when one reads the original alchemical texts carefully, as C.G. Jung did in the course of his psychological studies, one discovers that alchemy’s transmutation of base metals is purely metaphorical. The art was actually a complex system for probing the depths of one’s psyche. Serious alchemists were involved in a process of self-understanding and interior knowledge. The Philosophers’ Stone was a symbol for a transcendent psychic achievement, whereby one divested oneself of all baseness and ignorance and became a mature and fully realized individual, in touch with one’s deepest self and the divine source of that selfhood. In short, gaining the Philosophers’ Stone was analogous to achieving the state of the Buddha, or becoming a Zen master, or attaining Epicurean ataraxia, or being reborn in Christ.

All this would be merely ancient history if it did not have some relevance to understanding what went wrong in poetry during the last century. It seems to me that we can learn a lot about our art’s troubles and decline if we think in terms of alchemy and the Philosophers’ Stone.

Poetry lost its bearings when, for a variety of reasons, poets and critics began to insist that poetry had to serve a psychologically transformative function. Instead of being seen as a craft, passed down from master to apprentice, it became a mystical experience through which psychic wholeness was attained. The poem was now supposed to be doubly healing: it allowed the poet to express himself in a therapeutically restorative way; and it took the reader through an educative process that consoled his troubled spirit. Poetry became the Philosophers’ Stone—a magical talisman of transformation.

How did this happen? Well, at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century, a deep dissatisfaction began to develop in the Western world with the traditional aspects of poetry. Certain influential people no longer wanted rhetoric, ornamentation, rare diction, ritualized speech, or any kind of artificial beauty in their poems. They didn’t even want rhyme, meter, or tropes. Instead they hankered after a “pure” and “clean” poetry that would dispense with all these traditional niceties and give them unalloyed perception, unmediated experience, and absolute verisimilitude.

What they wanted was a literary version of the Philosophers’ Stone, which would bring them psychic wholeness. As Arthur Mortensen has suggested in a different context, they began to think of the poem as the Eucharistic Host.

This changed perspective was a disaster. It arrogated to poetry a function that properly belongs to religion, but even worse, it allowed for the progressive neglect of that which in fact is the source of poetry’s real identity: the conscious love of language and linguistic possibility. Instead of being the perfect verbal artifacts of skillful wordsmiths, poems became bogus narcotics promising the reader some kind of ecstatic emotional trip. The notion began to spread that poetry was about one’s “feelings,” and that notion triumphed in the end. Today there isn’t a poetry workshop in this country where that idea isn’t taken for granted by both students and directors.

The desire for a transformative emotional experience is essentially a religious impulse. I find it interesting that this new attitude towards poetry started to develop in the Western world at precisely the moment when doctrinal religion began to lose its grip on the European intelligentsia. By 1890, otherworldly faiths seemed discredited in the eyes of many persons, and all of a sudden poets were prepared to become, as Arthur Mortensen has said, “priests of a secular religion.”

But poetry cannot substitute for religion. First of all, the posture is arrogant and unbecoming, since most poets are lacking in the prestige and credentials that make for hierophantic status. Think of the pathetic little nerds you know in the poetry world, with all their personal faults and narcissistic self-absorption. Can you imagine any of them offering you salvation? No—as the Marines would say, they just don’t pack the gear.

Second, no one’s soul was ever saved by art. The arts are magnificent blessings to human life, but they are merely that, nothing more. I am a strict l’art pour l’art partisan because I want art to be free from political and moralistic meddling. But I am also committed to that view because I know that the deepest questions in life are not answered by artists, no matter how gifted they may be. Art has a license to do exactly what it pleases precisely because all the serious issues of human existence are decided elsewhere on non-aesthetic grounds. Only modern poets are stupid enough not to recognize this brute fact.

The notion that a good poem must be salvific is not the only alchemical parallel in the new poetic ideology that emerged in the early twentieth century. Another is the cult of gnostic difficulty. The alchemical process was notoriously complex and intricate, involving all sorts of arcane mystifications and convoluted by-ways. Those who practiced the art took many years to attain the Philosophers’ Stone, or at least they claimed to. So also with modern poetry, which was supposed to be difficult to write, and equally difficult to appreciate. Cranking out a poem in a few minutes was unthinkable. Like the alchemist, the poet was expected to distill a perfect poem over an extended period until he had something quintessential. For example, how long did Pound labor on that pretentious two-line squib “In A Station Of The Metro”? Six months? Such ostentatious effort was supposed to make the poem valuable, like a gram of pure radium.

It’s a curious thing about this mystique of difficulty. According to it, vast energy and complexity are involved in making a poem, but the resulting poem is a thing of sublime simplicity. By “simplicity” the mystique does not mean something easy to comprehend—far from it. It means simplicity in the alchemical sense, the quality of a substance that has been distilled and condensed into the purest and most unalloyed state, like the Philosophers’ Stone. This is why so many contemporary poets speak of reducing or paring down a poem until they are left with its pure essence. They are thinking like alchemists.

It is also why they instinctively hate formal verse. Their gorge rises at the thought of an adjective being added to fill out a metrical foot, or a syntactic structure being recast to accommodate a stress pattern. That sort of thing, they scream indignantly, muddies the “essence” of a poem. Such language is right out of the old treatises on transmutation. It shows that at bottom these contemporary poets see the poetic task as analogous to that of the magician or sorcerer or alchemist, who must concoct a potent charm according to an exclusionary ritual that banishes all “impurities.”

If you read certain poet-critics of the early twentieth century on questions of composition, you will see the virulence of this new attitude. Ezra Pound, Ford Madox Ford, and T.E. Hulme all loathed the traditional pomps and honors of poetry, and they actively sought to limit the art by paring it down to something lean and mean, so to speak. They went through the mansion of poetry like lunatic housekeepers, throwing away nearly everything. This reductionist attitude lay behind Pound’s manic command to “Simplify! Simplify!” It lay behind the famous “Do’s and Don’ts” of Imagism. It lay behind W.C. Williams’ “No ideas but in things.” It lay behind the generalized contempt that they all had for “Wardour Street English”—that is, non-colloquial diction and syntax. There was never a more Puritanically destructive period for poetry than the years between 1890 and 1922.

Percolating through the minds of these modernist reformers was the alchemical notion that the dross of poetry had to be purified in order to produce a precious reality purged of anything that did not immediately serve to give readers a blinding insight or an emotional orgasm. Poetry had to hit you like mainlined heroin, or it wasn’t any good. Thousands of deluded people still believe this.

This is why, in the typical poetry workshop today, you will be exhorted to avoid adjectives, to shun all abstractions and Latinate terms, and to write only simple declarative sentences. All this makes for a pinched, reticent, telegraph-code type of poem, but one that has great prestige because of its “purity” and “intensity.” If people can’t fully understand it, so much the better. As a poet you are an alchemical adept, and your work gains in reputation as it grows more hermetic and opaque. And when that happens, the door is left wide open for what I have elsewhere called Portentous Hush, a kind of highfalutin sanctimony that infects nearly all poetry today, whether free or formal.

I mention formal poetry because I see little evidence that our movement has liberated itself from these alchemical chimaeras. Too many New Formalists continue to believe that their poems are talismans of psychic transformation rather than just well-constructed verbal artifacts. They want their poems to “move” people, the way an electric shock moves the nervous system, or a laxative moves the bowels. But this alchemical-modernist delusion must be abandoned. Only fools turn to poetry for salvation, uplift, and edification (i.e. something that creates movement in the soul). Intelligent readers come to poetry for pleasure. An intellectual, literary, verbal pleasure to be sure—but pleasure nonetheless.

Also, many of us who should know better are still in thrall to the notion of alchemical purity and simplicity. Some time ago a prominent New Formalist wrote disparagingly of the use of adjectives, saying that he hated poems where the nouns were all “properly chaperoned by adjectives,” or something to that effect. Well, apart from predicate use, what the hell else does an adjective do except chaperone nouns? It seems to me that if you dislike a part of speech on principle, then you had better explain why. When a major figure in our movement suffers from this sort of unconscious modernist bias, we have to rethink exactly what our poetic practice is supposed to be. Otherwise we will have what revolutionaries call “colonized minds.” This means that although we have externally thrown off free-verse hegemony, we are still mentally enslaved to its basic premises. “Chaperoned by adjectives,” indeed! I suppose he also thinks that noun-subjects tyrannize verbs.

This deep-seated distrust of words in all their fullness lies at the heart of poetic modernism, which was a kind of Puritanism applied to language. It was a reflexive rejection of all verbal richness and rhetorical amplitude in favor of small-scale intensity. It is a restrictive, shackling, choke-hold on both expression and perception that has been strangling us since 1910. Why do we tolerate it?

We tolerate it because we are unaware of our colonized minds. The alchemical notion of a pure poetry, divested of all earthly dross and thereby possessed of the transmutational power to change and uplift us, still controls our thinking. And for as long as this mental colonization goes unchallenged, New Formalism will remain nothing but the iambic pentameter version of modernism.

How can we banish this deadly idea that poetry is salvific and transformational? How can we suggest to people that good poems are not Philosophers’ Stones that will transmute their base existence into something glorious? How can we convince them that if their souls are sick they need to visit a priest, rabbi, or minister, and not the director of their local poetry workshop? In short, how can we show that poetry is a human craft, and not a gnostic mystery cult?

It will be very hard to do any of the above, because success would require a reorientation not just of poetic practice, but of authorial motivations. We would have to convince vast numbers of poets that their poems ought not to be seen as therapeutic way-stations on the road to self-discovery. And believe me, that would be excruciatingly difficult. Many of them write for the sole purpose of feeling better. Poetry is their narcotic of choice, as whiskey or sex is for some other persons. The notion that a good poem is just an objectively beautiful creation that shows the virtù of its maker will not satisfy their emotional addiction.

Let’s be very clear on this point. I’m not talking about vanity. All writers are vain, in that we love to be published and praised. That’s just a standard human fault, and not an especially serious one. I’m talking about something deadlier—the need of some poets to speak in a voice of vatic authority, and to believe that our words are earthshaking utterances that fulfill our personal needs for self-expression and self-esteem, while moving others in ways that gain us applause and celebrity. Such an attitude is much more than simple vanity. It is a longing for some sort of earthly apotheosis. It is a belief that one has alchemical powers to produce a Philosophers’ Stone out of words.

What does such a stone provide these addicted poets? That’s easy enough to tell: fame, charisma, power, affluence, fashion-chasing, self-regard, egotism, snobbery—all the poisoned chalices that up-to-date trendy people are desperate to drain. Getting brainless secularists to give up these goals would be about as easy as convincing Michael Jackson to join the Carthusian order. It is exactly the sort of thing the Romans dreaded, and why they placed a slave in every triumphal chariot to whisper the following sentence in the ear of the conquering general: Memento te non esse deum—Remember that you are not a god.

Who will whisper to us that we are not gods? I don’t know, but the alchemical delusions have to be shattered somehow. Perhaps we alone can remind ourselves that poetry isn’t a religion.

I am also reminded that one of the historic reasons for the eclipse of alchemy was the growth of modern chemistry. Humble, unassuming workmen toiling in laboratories created the science. They did so not by looking for some quasi-divine stone that would save them and the world, but by a disinterested and practical examination of the physical properties of material. Bit by bit they gleaned facts about the universe, and gave us a science that really transformed human existence. If poets today could look upon themselves as ordinary competent chemists who make compounds out of words, rather than pseudo-priestly alchemists who promise psychic wholeness, we might be on the road to recovery. We would be honest craftsmen, and not traffickers in bogus mysticism.

.

Originally from Expansive Poetry Online

.

Author’s Note:

This essay appeared over twenty years ago, and caused a small firestorm of vituperative criticism from several persons. I did not respond, since the critics were motivated by personal and political animosity rather than by any reasonable disagreement. I still believe that I touched upon a major psychological distemper in the modernist movement—one that still affects much poetic practice today.

To forestall the objection that I have disregarded poetry’s role as a vehicle for the expression of deep feelings and intense emotions, let me say that I certainly believe poems can sometimes be of that nature. The real point of my essay is the contention that it is dangerous and silly to approach poetry as a mystical panacea for one’s spiritual and psychological problems. Such a notion is a form of idolatry that has led to an avalanche of bad, sentimental, subjective, obscure, and navel-gazing poems, all of them narcissistic or puerile. It is much healthier to see poetry as an honest craft that produces linguistic beauty.

.

.

Joseph S. Salemi has published five books of poetry, and his poems, translations and scholarly articles have appeared in over one hundred publications world-wide. He is the editor of the literary magazine TRINACRIA and writes for Expansive Poetry On-line. He teaches in the Department of Humanities at New York University and in the Department of Classical Languages at Hunter College.

Not sure if you’ve ever come across this little gem, Joseph, which involves some basic chemistry!

Johnny was a chemist,

but Johnny is no more;

for what he thought was H2O

was H2SO4.

I’ll have a thorough read later.

Joseph, your essay is a transcendent masterpiece of majestic importance. The brilliant interplay between the philosopher’s stone history and what has happened to classical poetry appreciation is a great comparison like a beacon shining its light over the murky depths. I am in awe of your linguistic prowess and your quintessential sagacity. I regard modern poetry, as well, as something the lazy foist upon us in blank verse prose form without having the discipline to at least make an attempt at meter and rhyme, my two basic values of classical poetry.

Many thanks, Roy. I too am impatient with the laziness and fake profundity of much modern poetry, though I do make some important exceptions for writers like Ogden Nash, E.E. Cummings, and Wallace Stevens. Eliot, Pound, and Crane also produced some fine work, because despite their modernist loyalties they were still great poetic craftsmen.

This essay raised such a stink when it first appeared that I received not just on-line insults, but also some threats, and friends warned me not to attend public readings. It had apparently touched a very raw nerve in some fellow poets, who were deeply attached to the idea that a poet should always “speak in a voice of vatic authority,” even if all he spouted was meaningless unmetrical drivel.

Cogent and provocative as always, and even this poetaster found a measure of inspiration in it.

Adjectives are meat on bone!

Adverbs add a verbal spark.

Nouns and verbs if left alone

Leave Erato in the dark.

“Crazy” doesn’t tell us much.

“Madcap lunacy” says more.

“Wrathful ire” keeps us in touch,

“Upset” only brings a snore.

Without rhythm, rhyme or form.

Writing poetry’s a snap

Poetry as prose? The norm.

Scribble words and take a nap.

Start your verse with “Old school tie?”

It could lead you anywhere!

If your poem starts with “I,”

It will go downhill from there.

Words, like lovers, should create

Ecstasy in their caress.

But when words are second-rate

Poetry will evanescence.

James, I’m with you on this. A good poem has to be interesting, provocative, saucy, unpredictable, a little bit in-your-face, and maybe even a tad offensive. Above all, it must not be boring.

The trouble with a poetry that sees itself as salvific and transformational is that it very easily slips into being unbearably pretentious. It’s why people exit poetry readings today looking like they are spaced out on Nembutol.

Right, I’ve read through the whole essay. Just a few things that come to mind.

In my opinion, you don’t want to overpopulate any type of writing with adjectives and adverbs, but a well-placed adjective or adverb (especially an adjective) can be just what a turn of phrase or a description needs. Overuse is generally the problem, I feel.

Stephen King, in his memoir/writer’s guide makes a big thing about cutting out adjectives and adverbs, though he does tell people reading ‘On Writing’ not to quote his earlier works which are choc-a-bloc with such ‘darlings’. Most folk who loftily tell you to suppress your adjectives will invariably quote ‘On Writing’ to ‘win’ the argument.

I just went through Ozymandias. Thirteen adjectives, no adverbs, from about 100 words – so about one in eight of the words are adjectives. (I sound like the intro to that ‘poetry’ book using graphs to rate poets in ‘The Dead Poets’ Society)

About removing profundity from poems, there’s a poem which I’ll submit to the SCP once the Maria W Faust sonnet competition is over, called ‘The Tree of Life, Bahrain’ which I wrote about a true experience. We were hung over in Bahrain and for no particular reason went in search of the Tree of Life (many places have them). In the end, having located the Tree, we had a rest, took some snaps and buggered off. Nothing profound at all, but I realised that was the perfect ending rather than some highfallutin revelation.

Anyhow, thanks again for the thought-provoking essay, Joseph, and don’t eviscerate me too much.

Paul, don’t worry. I have no immediate plans to eviscerate anyone.

Every part of speech has its place and it uses, and I think the impulse to forbid or greatly limit adjectives and adverbs is driven by a political agenda, and not a stylistic one. Sentences that are without adjectives or adverbs are stripped of nuance and complexity, and become nothing but bare statements that can either be affirmed or denied. The resulting plain and unadorned style becomes an attack on rhetoric itself, and a way to dismiss out of hand the great bulk of inherited text, by suggesting that any ornate language is laughable and therefore silly and unworthy of attention.

This serves a political purpose. It discourages students from consulting any text from the past that doesn’t comport with modern ideology. And this excuse is given: “That stuff is so ornate and complicated that it’s unreadable.”

The “highfallutin revelation” is precisely what modern lyric poetry demands. Everything that the poet says has to quiver with trembling significance — his poem has to be some kind of little dipshit epiphany of perception and ecstasy. Here in New York we have a “Poetry in Motion” series that has run for decades, posting short poems in our subway cars. EVERY SINGLE POEM POSTED, without exception, has been of this predictable type.

Thank you for your comments.

I agree with you about the way that poetry has become for many today a sort of substitute religion. Various historical factors over generations have led to this. During the Enlightenment period, human reason and science were elevated over all external authorities to such a degree that many intellectuals of the era looked on all “revealed” religion as a fraudulent and despotic imposition on mankind to be rejected; if they retained any belief in a “higher power”, they tended to become Deists and pantheists. The universities themselves which had been founded as Christian institutions, fell into the hands of Deists and rationalists for whom God was seen as an “absentee landlord,” a divine Watchmaker who made the universe and left it to run on its own, about whom we know virtually nothing, since He does not intervene supernaturally in history. Such a God can hardly be worshipped, since He is unknown and does not interact with human beings in a personal way.

The rejection of the God of Scripture by Western intellectuals did not, however, destroy the religious impulse in the human heart. So instead of worshipping the Almighty, personal, God of Christianity and the Bible, who acts in history, hears prayer, and interacts with man as a creature made “in His image,” there was a push to worship the “God within”—seen as an impersonal creative force manifesting itself in the world, through the historical process, and in a special way, through “avatars”–figures in history who are enlightened and in deepest touch with their “inner deity.”

In this context, the poet began to be seen as virtually an organ of divine revelation. The role of the poet thus took the same place in secular circles that prophets occupy in revealed religion; poetic utterances began to be seen as oracles through which the “god within” the poet had spoken. This was a departure from the earlier Christian view which sees the poet, not as a prophet, but as a gifted individual who has received artistic gifts from God and must develop those gifts through practice, and the gradual acquisition of knowledge, skill and craft. A Christian view of poetry sees the poet as a craftsmen, who uses the gifts he has received from God to compose artistically skillful reflections on aspects of human life and experience he feels moved to write about, because he finds the subject matter interesting, entertaining, humorous, unusual, nostalgic, touching, moving, stimulating, or perhaps, because he regards the subject matter as morally, spiritually, or politically true, important, and in need of being said with rhetorical and persuasive force. The poet expresses his thoughts in a way that is pleasing to the ear and arresting to the imagination. In this context, one can speak of poetic “inspiration,” if one means by this simply that God is the Giver of artistic gifts, and equips the poet with the skill and ability to write as he does just as He equips athletes with athletic ability, musicians with musical ability, doctors with healing skills, etc. But as you rightly point out, to view poetry writing as a form of prophecy tends turn poetry into a sort of substitute religion for a secular age.

Such a view also makes it easy to pooh-pooh the laborious “craft” element of poetry as artificial and contrary to the inspired nature of “pure” poetry, which—if it is “authentic,” must be brought forth ecstatically in a state of mystic exaltation. Poetry readings in this view becomes a sort of secular religious ritual, like people gathering around a medium in a séance to hear messages from the other side. In this context, poets really do act as the high priests of a secular religion and their oracles are held in awe as virtual objects of worship. And that is, as you point out, both pretentious and idolatrous.

Thank you, Martin, for your thoughtful and detailed comments.

The Enlightenment is responsible for many spectacularly bad things: political upheaval, religious skepticism, utopian fantasy, and the transformation of warfare into an all-consuming Frankenstein monster. Its effect on poetry might be small in comparison to such things, but just as unwelcome.

Without God, man’s already tragic fate becomes even more tragic, because he now faces a universe devoid of meaning or purpose. Even more terrifying, it is a universe that is just as unconscious and unfeeling as a rock or a sandbank, and therefore totally indifferent to human suffering.

A poet, under those circumstance, has two options: either coldly describe the nothingness and emptiness and meaninglessness, or try to find whatever meaning he can create in words out of some small epiphany. You can then call him a “priest,” in the sense that he is performing some kind of ritual, or a “prophet,” in the sense that he is acting as a mouthpiece for some unknown power. But in either case he is acting as an ineffective substitute for religious belief that has been exploded or refuted.

The whole thing brings a comic image to mind: imagine man trying to fry a steak with nothing but a small book of matches, which he lights one at a time to heat the bottom of the frying pan. That’s what it’s like to have a poet as a priest.

Dear Dr. Salemi,

A splendid essay! Thank you for sharing it with the SCP. As far as I can tell, it can’t be found anywhere else online (or if I’m wrong, please feel free to include a link to an earlier location in the comments).

A few thoughts for you and other readers:

1. The problem identified in the essay has occurred in tandem with the decline in mainstream appreciation of the poetry most prominently advocated by the largest poetry bodies. There are a large number of people out their who appreciate traditional poetry but are not receiving it. This is similar to a neurological disorder whereby the body needs and craves something but the brain is not providing it. It is a sickness and Dr. Salemi has well diagnosed it!

2. Poetry can be mysterious, mystical, magical, enlightening, profound, moving, and many other things, but ultimately it exists in a secular sphere and can only act as a prelude or bridge to one’s ultimate spiritual path and calling in life. If the poetry becomes an end point in itself then it is missing the point and has gone off track, leading to 1 above. The exception is if a poem is part of the actual spiritual teachings of a faith such the Books of Psalms in the Bible or perhaps the Book of Songs in Confucianism.

3. While putting a limitation of prelude or bridge may seem limiting to the modern poet, there is actually much here that is left to be tapped. Poetry is a bridge to theater, to all literature, to culture, to education, to music, to cooking recipes even (See Mary Gardner’s recent poem: https://classicalpoets.org/2023/05/01/a-recipe-and-a-poem-chicken-and-andouille-gumbo-and-other-poetry-by-mary-gardner/). For example, my kids high school is a relatively new private school and I recently had the opportunity to write the lyrics for the school song, which seemed to go over well. This is something real that people can use in their day-to-day lives. Additionally, in the somewhat recent World War I movie 1917, which earned many accolades, the poetry of both Kipling and Lear is featured. This is to say that many spheres in the world need and benefit from classical poetry, just ask General Patton.

Just my two cents.

Thanks for the added remarks, Evan. The essay used to be online but has not been for a very long time.

There is a real hunger out there for traditional rhyming and metrical poetry. Whenever the general public is questioned about their poetic preferences, they largely ask for memorable poems that they learned in school. There was apoplectic rage in the UK some years ago, when a survey of the British public showed that Kipling’s poem “If” was still the overwhelming favorite. The smug free-verse partisans who run UK workshops and English departments went ballistic with fury.

There are religious and devotional poems that can lead to spiritual growth and faith. But the poems HAVE TO BE GOOD, aesthetically. One mistake that some believers make is to think that all a religious poem needs is its orthodoxy and piety, and any failures or defects will be forgiven. But that is a grave error. A badly composed or amateurish religious poem only holds religion up to ridicule. The excuse “He means well” cuts no ice when you are judging a religious poet who is incompetent in craft.

I agree that poetry can be a bridge to many things. I loved Mary Gardner’s poem on chicken andouille, and there can be ekphrastic poems on works of art, historical narratives, comic or erotic pieces, political satires or lampoons… and everything else. But when poets think that they have to be priests of a secular religion who must speak in tones of mysterious sanctimony, they just won’t write that kind of stuff. It’s beneath them.

For anyone interested in adjectives in poetry, I think the best examination of that subject is available right here at SCP.

Poetic luminaries like Dr. Joseph Salemi, James Tweedie, Peter Hartley, Susan Jarvis Bryant and others offer their perspectives in the comment section under Susan’s poem, ‘Hummingbird Communion.”

https://classicalpoets.org/2020/05/20/hummingbird-communion-and-other-spring-poetry-by-susan-jarvis-bryant/

Joe, as with all of your admirably crafted, thought-provoking essays, I read them with interest and always come away with something to think about. This time it’s these two observations: “poetry cannot substitute for religion” and “no one’s soul was ever saved by art”. They leapt out at me as soon as I read them.

I dread the thought of poets being “priests of a secular religion” – a wonderful turn of phrase from Art Mortensen. It makes me cringe to think what damage this attitude can do to the newly emerging creative mind… a mind prone to being constrained by the rigid doctrines of those treading the “righteous” poetry path – a path where all those with ideas of their own are expected to rein personal creativity in and follow these pious “poets” to a destination where there’s no room for those who don’t bow to the self-declared Priests of Poetry. Thank you, Dr. Salemi. Your words have encouraged me to continue to ignore these false prophets.

Thank you, Susan. When I published this essay many years ago, some of the negative responses that I received insisted that in many cultures poets were considered “special” and “blessed” and “of a higher order” than the rest of us. One objector mentioned the ancient Irish bards, and another brought up the Roman term “vates” for poet, and how it could be a synonym for soothsayer or prophet. The basic idea behind all of these superstitious objections is that the poet functions as a witch doctor, and has a mystical link to a magical world beyond us.

The notion goes back to the idea of Plato that the poet is nothing but a mouthpiece for the exhalations of some god who possesses him. Now I don’t deny that a poet can get into a kind of trance sometimes, and plug into a deeper unconscious level of his mind, and then bring forth work that is special and striking. Sure, that can happen on occasion. But the idea that the poet always functions this way is absurd. The bulk of any poet’s labor involves simple sweat and energy and thought, just like a carpenter’s labor in building a fine piece of furniture.

Part of the problem today is the ubiquity of the confessional lyric mode, with its dependence on emotion, sentiment, and the small-scale epiphany. This pulls poetry in the direction of being short, ambiguous, and serious-sounding pronouncements, like the messages from the Delphic Oracle. And even when the poet tries to write something longer, the crabbed, clipped, and gaseous characteristics of the lyric poison his work.

But what can one expect , when even a major figure in New Formalism (Dana Gioia) says that all poems today must have “a lyric frisson”?

Well, to me, a chewy cryptic lyric poem is a glorious pleasure!

I’ve thought a lot over the years about the association of poetry with salvation. It’s hard to dissociate the two because they are intrinsically associated. Partly because poets want their work to be associated with salvation. But, more radically, because God wants to associate poetry with His saving work. And He does what He wants to do.

The Psalms are the chief example. I’ve come to believe that, as Our Lord entered His Passion with a Psalm and finished it with an utterance once David’s, He was reciting Psalms interiorly in His humanity throughout the way of the Cross. The Psalms are the interior landscape of Calvary and so they are very closely associated with salvation.

Another example is Our Lady, who with her Spouse the Holy Spirit, composed the Magnificat and had it published in Luke’s gospel, under her own sweet name. Everything she did was always associated with salvation. And more than that she’s an example for every Christian in every walk of life: including the poetry walk.

Now for the association of poetry with prophecy: the sayings of the Biblical prophets are also more often than not preserved for us in poetry. Pre-Christian pagan poets too had moments of prophecy, when “thoughts beyond their thought to those high bards were given” (as quoted by St. Newman).

Yes, the Scriptural canon is closed. But the life of poetry goes on and it’s because God wills it. Poetry, like every non-sinful human activity, can absolutely be put at the service of the apostolate, and the goal of the Christian apostolate is the salvation of souls. The life of poetry goes on and God continues to incorporate it into the ongoing work of salvation.

Also He continues to grant inspiration (not of the Biblical level but of a lesser but analogous kind) even to poets outwardly dissociated from His Church. Why? It’s extension of his unfathomable Mercy.

Poetry isn’t the source of salvation but it is one of salvation’s little handmaids (and unique among them). I think my meaning here is very close to Evan Mantyk’s when he wrote that poetry can be a bridge. The more lowly and little and unpretentious and built for foot travel we make that bridge the more mystical it becomes and there’s nothing anyone can do about it.

Some good poetry is very simple. Some is very arcane. In both cases, wisdom is vindicated by her children. We want our poems to participate in the virtues of Mary’s Magnificat and sometimes God grants this. He is wonderful like that!

Dear Ms. Cooper —

What you say is plausible in a limited way, but not in a universal way.

There are many poets (both in the past and now) who did not associate their work with salvation, or even imagine such a connection. Many of them were atheists or non-believers or skeptics. They can’t be shoehorned into some kind of generalized Catholic apostolate.

For this reason, it is an error to say “We” when discussing what goes on here at the SCP. Poets of many different faiths and philosophies come here to publish their work. This isn’t the Society of Catholic Poetry, but the Society of Classical Poetry. The society has a very specific aim — the resuscitation of the formal and metrical poetry of our Western tradition. That aim is not salvational, but aesthetic. The SCP doesn’t exist to convert persons to a particular religious creed.

Sure, some poems can be handmaids to faith and salvation. But they are handmaids who are not on salary, and who do their work in a purely voluntary manner. Sometimes good poems can be purely secular and shockingly irreligious.

When I said “we” (in the second to last sentence) I didn’t mean this Society but you and I. Only you can correct me if I was wrong in that but, even if I was, I know I’m not alone in the aspiration I expressed there.

Yes, some good poems can be purely secular and shockingly irreligious. One I really loved was the one you translated: “Easter!” Because it said something true and sharp about Church corruption. The secular poet did a service to the Church and her goals, salvation of souls foremost, by writing that poem. Whether he intended it or not. (And looking again at the poem and the note that went with it, it looks like he didn’t. Though intentions always lie deep.)

I go with Justin Martyr that if it’s true it’s Christian. And if a poem is good, God is the ultimate source of its goodness, even if an unbeliever wrote it.

The human aim of something doesn’t prevent God from using it for His own ends. And we (you and I) know that salvation is high among them.

The Western tradition (including the poetic-literary tradition), ever since Christ’s conquest, is deeply Christian. Even though viruses like Marxism get in and do damage. And the Western-Christian tradition is famous for cultural appropriation and why not? All things are ours, we are Christ’s and Christ is God’s.

Czeslaw Milosz, one of the modern poets I honor, put the question: What is poetry that does not save nations or peoples? I think he asked that because he *wanted* poetry to do that work and was grieved at its apparent impotence. And Shakespeare mourned over beauty “whose action is no stronger than a flower.” The apparent weakness and impotence of poetry to do big salvific things is part of its unique punch and power. It’s true, apart from God, poetry can do nothing. But the little flower springs from the old stock and the True Vine and sometimes from the crannied wall and God plucks it out and wields it.

I don’t think all good poems are serious or explicitly religious, far from it. Lightness is utterly desirable sometimes, as is weightiness. Lightness has its punch and power too.

Your comment on Justin Martyr puts me in mind of a related quote from St. Thomas Aquinas: “All truth, no matter who says it, is from the Holy Ghost.” If one takes both statements in a general metaphysical sense, they say that everything — good, bad, or indifferent — works to serve God’s ultimate end.

That’s true of course, but using it in an argument only clouds the mundane points being debated. My contention in my first reply to you had to do with countering the idea that the SCP needed to become an apostolate for Christian evangelization. I think that idea is misplaced and unworkable, and not appropriate at a website that does not have a specifically Christian mission.

Let me bring up something evidential, rather than argumentative in the strict sense. I have been a member here for nearly seven years, and in that time I (and several others (like Mike Bryant and Brian Yapko and James Sale) have made sure that the website was never colonized by left-liberals. As you know, once a left-liberal type ensconces himself at a poetry website, he immediately works to colonize it for those of his own viewpoint, and to purge it, slowly but surely, of any dissidents to politically correct orthodoxy. The SCP is practically the only literary site on the entire web that is a safe space for conservatives, rightists, Christians, and believers in traditional Western criteria for poetry, and it takes constant vigilance to keep it that way.

We haven’t done all that work to then allow the site to be colonized by some other group with another agenda. Several years ago there was a man here (a very devout Catholic) who wanted this site to become exclusively Catholic, and his commentary on every poem was to judge it by Catholic standards, even if the poem in question were not religious in any sense at all. He even attacked Joaquin Miller’s brilliant poem “Columbus” on the fatuous grounds that it did not mention Columbus’ religious faith and motivations. Eventually the man became intolerable, and left the site after much bitterness and savage argument.

Sometimes I wonder — the poets mentioned in my essay, who want to see themselves as priests of a secular religion, are almost always left-liberals, and what they write is basically a form of proselytizing for that religion. But there are some religionists here who seem to want to do the same thing, except with their religion as the favored one.

For me at least, poetry is a licensed zone of hyper-reality known as fictive mimesis. It’s not written to save the world.

You wrote: “My contention in my first reply to you had to do with countering the idea that the SCP needed to become an apostolate for Christian evangelization.”

I just want to re-iterate that the idea you describe here is no idea

of mine. The SCP is great the way it is and its parameters are genius.

You were the one who used the word “apostolate.” Twice. Here are your words:

“Poetry … can absolutely be put at the service of the apostolate, and the goal of the Christian apostolate is the salvation of souls. The life of poetry goes on and God continues to incorporate it into the ongoing work of salvation.”

That sounds like an agenda to me.

I used the word apostolate and stand by what I said but I did not propose that the SCP change its parameters in any way or that it become a Christian apostolate.

I may have a personal apostolate, an agenda if you will, but I’m not seeking to make my agenda or apostolate the agenda or apostolate of the SCP.

I think the SCP’s mission is brilliant as stated and I support it wholeheartedly.

Speaking of agendas, Dr. Salemi, I want to ask you something. You already know I’m a Catholic. I assumed until yesterday that you were too. But now, thinking more about that “Easter!” poem and the note that went with it, I have questions.

Are you a Catholic, Dr. Salemi? Are you a Freemason?

That “Easter” poem was written by my grandfather in 1954. I simply translated it.

I am a Council-of-Trent traditionalist Roman Catholic of the pre-Vatican 2 variety. I loathe the Novus Ordo mass, most members of the modernist hierarchy, a German church that is in open schism, and all so-called Catholic liberals.

I also KNOW that the lying impostor and flaming heretic Jorge Bergoglio is NOT the Vicar of Christ (as he himself admits). Since the recent death of Benedict XVI, the See has been vacant.

OK?

Ok.

I would like to respond in depth to this but I cannot as, coming back from a vacation, I am swamped with other work to do. Suffice to say: it is a brilliant article, brilliantly expressed, and highly imaginative in its grasp of the issues and fully informed as to its sources. However, on one preliminary reading I do have one caveat with it: it is almost too ‘purist’ for my taste, for any reader of my articles on these pages or my columns on The Epoch Times, will know that the Muse is at the heart of poetry and its absence in this article slightly pains me. Yes, we start with the skills/techniques and we really do need to practice them; we discover and uncover the major themes that typify and resonate with our thoughts, our emotions and our lives; but without the Muse, poetry cannot live. Perhaps Socrates overstated the position when he said, ‘I soon realised that poets do not compose their poems with real knowledge, but by inborn talent and inspiration, like seers and prophets who also say many things without any understanding of what they say . . .’ Taken at face value, that easily leads to the absurd excesses of Romanticism, and the worst of Byron; but the best of Byron (of which I think Joe is an avid student) combines all that discipline but there is too a Muse – hence the genius of Don Juan. anyway, I am rushing and I have not said this very well, so I hope you will forgive me, but I think you get the gist of what I am saying – regards.

But Jim — the Muse is merely a metaphor. She and her sisters were originally thought of as divinities (the daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne), and then relegated to metaphorical status, along with all of the other pagan gods, after the West became Christian.

What’s she a metaphor for? Easy — “inspiration.” But that word in itself is metaphorical. It means a kind of breathing in, an afflatus of inhalation that comes from… well, we don’t know where it comes from. All we know is that something hits a poet from time to time and allows him to do excellent work.

Since the operation of the Muse is invisible and unpredictable, she can be explained in many ways, not all of them religious. Maybe inspiration is just a psychological phenomenon, or the aftereffect of intense emotion, or a momentary burst of physical energy in a poet that is generated by what he eats or drinks. Maybe she comes on the heels of some long-forgotten memory that is regained by the poet, or maybe she is the precipitate that comes out of a mixture of random thoughts, a sudden realization, and intense conviction. Maybe she is produced by an overheard comment, or the smell of madeleines, or the finding of a lost object — things meaningless in themselves, but effective as catalysts of creativity.

Whatever she may be or where she comes from, we certainly know that she exists and is effective. I didn’t mention her in my essay because I was concerned with describing a false ideological notion of what poetry is — a notion that is really choking and strangling much poetic composition these days. My assumption was that all my readers would know that inspiration (The Muse) is a crucial part of poetic composition.

I hope you will find time to comment more on the essay. I value your opinion.

The more one reads Joe’s essay, the profounder it becomes; there are literally ideas brimming and weaponised in his account of modern poetry and ‘where we are’ now. There is too much for me to cover in what I want to be a brief yet more considered reply to his thesis. Two things, I think, are of primary importance.

First, his point about the Muse being a metaphor, which is correct; it is. But in pointing that out we also need to say that all language is metaphorical; indeed, our thinking is metaphorical. We can only seem to understand anything in relationship to something else. In other words, we don’t see things as they are; we construct a map – of words. Guess idolatry is when we mistake our constructs for reality. The promise of religion is that one day we will ‘see’ things as they really are – face to face, as St Paul puts it – but, not now!

GK Chesterton put this in a very ingenious way when he said, “It is a strange thing that many truly spiritual men, such as General Gordon, have actually spent some hours in speculating upon the precise location of the Garden of Eden. Most probably we are in Eden still. It is only our eyes that have changed” Blake said something similar when he wrote of ‘To see a world in a grain of sand …’ The spirit of the Muse is what enables some to see ‘the Garden of Eden’. At least, to see in that compromised way of metaphor: the language can, not in an absolute but relative sense, enable the spiritual to become more real, or more exactly, move more into focus and prune the deadening effects of pure materialism. Hence, in true poets, the lack of cliche, lack of tired imagery, lack of worn diction, lack even of tired forms – the metaphorical power the Muse enables refreshes life and our ‘seeing’ of it.

The second point, possibly even more important, that Joe explores is the true statement that poetry is not religion and is not a substitute for it. Absolutely, salvation is by another route. A great example: it’s really fascinating the interaction between Dante the pilgrim and Brunetto Latini in canto 15 of the Inferno. It’s very, very moving: Brunetto was one of Dante’s mentors/masters – he is in hell (it’s unstated but for practising sodomy) – and he is there along with a long unlisted group of “very celebrated writers”. But the touching thing is his final words to Dante as he is compelled to move: “… let me commend my Treasure to you / in which I still live, and I ask no more ..” The ‘Treasure’ is his book, an allegorical didactic poem, Il tesoretto. Ah, literary fame – all that he has left as he parts from Dante forever. Dante, ironically, since he learnt how to achieve ‘immortality’ from his friend, is really spurning the idea that literature leads to immortality or salvation: there’s a book doing the rounds and that’s it; as for Latini himself, he is racing round an endless hell.

We deceive ourselves when we think that anything material can save us. But that’s the problem with the modern period: in the absence of real religion, people abhor a vacuum, and so choose something else. High-brow perhaps to choose poetry; low-brow maybe to get stuck into heroin! We are in a world in the West where there is a profound crisis of meaning – the lack of The Word, the Meaning. So we are frantic for substitutes – the ersatz and the ultimately unsatisfying. In such a climate it is unsurprising that reams of really bad poetry – non-poetry in fact – is being written.

Not a specifically religious person, but a perceptive one, Yuval Noah wrote: “Just as the C19th created the working class, the coming century will create the useless class. Billions of people are likely to have no military or economic function. Providing food and shelter should be possible, but how to give meaning to their lives will be the huge political question.” Of course, for the non-religious it is a political question, since they abjure the presence of the invisible; but for those who seek the invisible reality (called God in the Western tradition), it is a spiritual issue: as Thomas Moore observed, “When soul is neglected, it doesn’t just go away, it appears symptomatically in obsessions, addictions, violence and loss of meaning”. These we see everywhere on the increase.

Thus, I agree with Joe that we should “be honest craftsmen, and not traffickers in bogus mysticism”, but I also think that, as Patrick Harper noted, “In bowing our heads humbly before the Muse, and losing ourselves in her imagery, we paradoxically gain greater freedom and meaning, and come to know what it is to be our true selves.”

Finally, just let me reiterate how brilliant I think Joe’s article is: I am simply providing some supplementary ‘thoughts’, along the way, but the article itself is, in my view, a kind of – to use a metaphor – 6th Dan Black belt composition. Very powerful indeed!

James, thank you for your perceptive and intelligent commentary. When you mentioned General Gordon and his fascination with the Garden of Eden, and how an invisible Eden may in fact still be all around us, it made something click in my mind. Why have so many poets (myself included) been drawn to write about imagined gardens of peace and tranquility and absolute perfection? Why is the literary topos of the “locus amoenus” so common? It is, as you say, to “enable the spiritual to become more real.” Or, to put it differently, to give embodiment in language to an imagined state of order, control, and bliss.

When you say “in the absence of real religion, people abhor a vacuum, and so choose something else” you have touched on the same vital truth that Chesterton once expressed: “When people cease to believe in God, they then don’t believe in nothing. They start to believe in everything.” Both statements are a profound diagnosis of what is wrong with the world today. The insane chase after crackpot ideas, trendy fads, mindless ideological nostrums, new mechanical gadgets, irrationality, perversion, sexual polymorphism, bodily mutilation, obsession with food and the environment — what is it all, except a desperate attempt to fill a deep moral and spiritual void? As you say, these things are “ersatz and ultimately unsatisfying.” But don’t underestimate their power as world-encircling epidemics of the mind.

This, in my opinion, is why we must begin to understand left-liberalism, and all of its accompanying insanities and freak shows, as a new-born and incipient religion. It isn’t just a different philosophy or political opinion. It’s a new faith. And that makes it very dangerous.

Thanks Joe – very useful – will get on it later this week!!!

This is all marvelous stuff! I hope the thread goes on forever. If not here, then in response to some soon-to-appear essay or poem. The refinements to the central thrust of Joseph’s argument have been particularly insightful. I believe that this is as close to consensus that we have ever had on this site. It is a joy and a pleasure to see it all expressed with such eloquence and respect. I would especially wish to hear what thoughts Margaret and Sally might have to add to the conversation.

A few thoughts in response to the conversation above… I don’t think SPC is in any danger of being seen as an “evangelistic” website with a religious mission! The diversity of themes chosen by the contributing poets on this website would prevent anyone from drawing that conclusion.

What distingishes the SCP website from so many other websites, however– in addition to its promotion of formal poetry–, is its openness to publishing poems on all manner of traditional themes, including religious themes. It does not, as Marxist-leaning websites would do, automatically push the “reject” button on submissions simply because they may address religious questions, express faith, or make mention of God at some point. And I think that is a wonderful thing about this website; its publishing decisions are not dictated by anti-religious prejudice. It recognizes that religious themes have played a major role in the canon of Western literature, with poets like Donne, Herbert, Milton and others frequently reflecting in their poems on themes of a religious nature. This a part of Western tradition inseparably united to the aims of a revival of formal poetry.

If God is the Author of all beauty, it would be very strange for a website that promotes the celebration of beauty to exclude in an a priori manner any poetry that happens to pay homage in some way to the Author of beauty. That would be most unnatural, just as it would be unnatural for a website devoted to Elizabethan poetry and plays to studiously avoid any mention of William Shakespeare. Anywhere beauty is celebrated, one inevitably “runs the risk” of running into beauty’s Author around the corner or hearing someone suddenly make mention of Him at some point.

That is because God enters into and conditions every aspect of human existence, ultimately. That is why poets who write on politics may find it hard to avoid all mention of God– especially if one is thinking about a subject like human rights, since American thinking on that subject, especially, is steeped in the idea that rights come from God, not government, and that government’s role is to secure natural rights given by God from above.

The founders apparently had not mastered the art of compartmentalized thinking, so as to to be able to write a “God-free” version of the Declaration.

The founders were not all Christians; but despite the differences of religious belief among them, they could not write the Declaration of Independence without making reference to God as the Giver rights and as the Judge of all men. But then they lived in days when people still believed in universal, objective truth, before the truth-seeking University had been replaced by the truth-allergic multiversity of today.

Mr. Rizley, nobody is saying that the SCP is an evangelistic website with a religious mission. But that doesn’t mean that there aren’t some people here who would like it to become that.

The trouble with evangelical types (of whatever denomination) is that they are insistently driven by their beliefs into pushing a message or agenda on others, and they fell compelled to do it “in season and out of season,” as the Scriptures say.

It’s exactly the same with leftists and liberals, who are also profoundly evangelistic about their ideologies. They simply WILL NOT STOP when it comes to pushing their beliefs on others, in every situation and circumstance. Like Jehovah’s Witnesses, they ring your doorbell at inopportune times and insist on talking with you.

I agree with you — the SCP is a place of freedom and unfettered discourse. Persons of many faiths, or no faith at all, submit material. We are honestly democratic here, in that Mr. Mantyk publishes polished poems, simple ones, beginning work by students and young people, comical and satiric material, expert translations… the only thing not here is free verse, and that is in accord with the SCP’s mission — to promote traditional rhyming and metrical English poetry.

The SCP also promotes proper English usage, correct spelling and grammar, a sophisticated vocabulary, adherence to genre requirements, and a living consciousness of older literary traditions and styles.

In leftist jargon, this is “a free space” for those who support such aims. (For the left the phrase is essentially meaningless, since for them a “free space” is one where everyone is compelled to adhere to the same ideological opinions.)

No one denies that religion (and the Christian religion in particular) is ingrained in Western culture and our literary heritage. And no one here wants to excise it or censor it. But the SCP is essentially concerned with aesthetic issues. Yes, of course poems will contain various ideas and doctrines, and the beliefs of individual poets will surely be present in their lines. But no one should come here with the proselytizing aim of converting anyone else to his religion, or judging a poem’s value by what opinion it happens to present.

I hope that clarifies my position.

See reply below.

“No one should come here with the proselytizing aim of converting anyone else to his religion.” What exactly do you mean by this, Dr. Salemi? Are you suggesting that Christian poets who write about their faith strip themselves of all religious motivation when they write? Do you really believe that any Christian poet who writes about his faith does so from a standpoint of complete and utter indifference as to whether his writing may contribute in some small way toward his readers becoming Christians or being edified in their faith if they are Christians? To insist that a Christian poet who writes about matters of faith must have no religious aim in writing what they write is to misunderstand the very nature of the nature of faith and of religious art.

When Francis Thompson wrote “The Hound of Heaven”, do you really think he was seeking solely to satisfy his reader´s desire for aesthetic pleasure, with no other desire, aspiration or hope regarding the effect that his poem might have on the spiritual life of his readers? Does not his poem not have, in some sense, a “didactic” purpose, insofar as the writer is making definite theological assertions about God through what he writes– namely, that God is a God of grace and mercy who relentlessly pursues the soul whom he overwhelms with his redemptive love? And in writing such a poem, can it be assumed that Thompson had absolutely no spiritual or religious aim? Thompson obviously would have desired that his readers experience grace as he had, and that no doubt, played a role in motivating him to write. It would naive to assume the opposite– for to assume that he would be indifferent concerning the spiritual effect of his writing on others contradicts the very nature of religious faith and religious art, which is always written with an ennobling, inspiring and spiritually edifiying aim. The Christian faith is essentially and inescapably “evangelistic” in nature. Everything that Christian poets write about God is written at some level with some measure of hope that their readers will find hope and peace and eternal life in God through Christ. If they did not have those convictions and those motives, they would not write poems about their faith. I cannot believe that Francis Thompson wrote to give his readers aesthetic pleasure without entertaining the least hope or concern that through writing about his own experience in a vivid, poetic, and emotionally moving manner, his readers, too, might be hunted down, as he had been, by the Hound of Heaven. To insist that religious poets strip away all religious motives in their writing is most unreasonable, in my opinion. However, the value of what they write, from a literary standpoint, must be judged by literary standards that apply across the board to all poetry.

I have thoroughly enjoyed ‘Poetry as the Philosophers’ Stone’ and followed all the interesting and informative comments… and now I’m a tad confused. For me, this essay is saying that poets should be free to write about any subject they wish; poets should be free to make any point they wish to make… but, the minute expectations are introduced, the genre is prone to suffocation. A poem may save a soul. A poem may set someone on the path to Christ. A poem may cure someone’s anxiety… but, no poem should be expected to do so. That’s where the word ‘agenda’ comes in. As soon as poetry becomes a slave to an agenda, freedom of expression is dead. Poetry should be able to express any opinion, even an evangelistic one… but, as soon as a particular opinion becomes the universal rule, therein lies the problem.

Susan, I am 100% in agreement with you. This is exactly what I mean to say. No poet is really in a position to tell another poet what must, or must not, motivate them to write. Poetic motivation is complex and sometimes not fully understood, so poems must be judged on their own merits as finished products that speak for themselves and that either do or do not possess eloquence, skill, creativity and literary merit. To put strictures on poems by laying down rules about what constitutes proper and improper “motives” in writing is to turn from literary criticism to ideological imposition. It is to focus more on the poet as a motivationally complex being instead of the poem as a literary product.

Rizley, you are confusing a motive with an agenda. Anyone can have whatever motive he likes, and I have never said otherwise. What I am wary of are poets who have an agenda that is not aesthetic, or aesthetic only secondarily.

In regard to Susan’s last point, consider this: if you have the agenda of converting others to your particular faith, then you are not going to stop at one person. Your evangelical commission is towards the entire group. Susan is quite correct when she says “as soon as a particular opinion becomes the universal rule, therein lies the problem.”

And that’s the issue here. If you have an evangelical commission, then it naturally is “universal” in scope.

Dr. Salemi, You seem to suggest that I might possibly have an “agenda” with regard to transforming the SCP website into something it is not already– but why would I want to do that? I believe in freedom of expression and would not want to change that for anyone on this website. I like a poetry website that allows for different writers with different viewpoints to express themselves. I have no desire to “colonize” the website, hijack it to a sectarian cause or do anything to it, other than participate in it. Even if I wanted to change it in some way (which I don’t), this is not my website to change; I didn’t create it; I am not involved in its adminstration. I am simply one of many people who have the privilege of submitting poems that I have written in the hope that others might read and enjoy them, and possibly receive some encouragement, blessing or insight from them, and might help me grow in my skills as a poet through dialogue or critique.

I write poems for the same reasons that many write poetry– because it is a “part of me.” It is in my blood since my early youth to express myself through writing. We all enjoy doing what we feel we are gifted to do. I derive immense pleasure from letting my creative juices flow while composing a new poem. In other words, writing poetry is for me a creative outlet that provides me with an opportunity for self-expression and artistic invention. I find this helps to provide a sense of balance and well-roundedness to my life that I regard as important. Moreover, people tell me that they like reading my poems, so I figure it is a worthy pursuit.

As a Christian, I certainly want to glorify God in every endeavor, in the hope that my life and words may serve to point people to Christ. I freely admit that, but that does not make me insincere in my desire to pursue excellence in writing? Every poet has his own worldview, beliefs, values and desires for his fellow men. The only “agenda” I have is that which every Christian is supposed to have– to reflect something of God’s goodness, beauty and truth in every endeavor I undertake, whether writing a poem or eating and drinking.

When does a motive become an agenda?

I believe that I’m called to write as an apostolate. Even my poems that aren’t explicitly Catholic or even explicitly Christian are still written with the Catholic worldview in mind, and in keeping with the idea mentioned in the Council of Lima in the 16th century that “one can hardly teach them to be Christian if one does not teach them to be men and live as such.” Hence missionaries have always introduced some Western customs (such as the family dinner at a table) along with the faith.

Many cultures have had customs that were impediments to faith and had to be overcome before the faith could make inroads. Because our culture is one of them, helping to overcome modern culture’s customs (as St. Justin Martyr said of the Greeks, “I find nothing in them that is holy or acceptable to God”) and reintroduce ideas, values, and customs we’ve lost is one of my motivations for writing. Does that make it an agenda, even though I always seek to write poems of the highest quality possible?

Either way, where is the line between motive and agenda drawn?

First, to Martin Rizley — Alright, we have no real argument. I have no desire to reshape this site to suit my preferences, and I fully believe you when you say that you feel the same way. We can bury the hatchet. On all other matters where we differ, we’ll agree to disagree. Let there be no malice between us.

Second, to Joshua Frank — I also find in your case that we have no real reason to fight. I’m happy about your apostolate and I ask God’s blessings on it. My pet peeve (not with you, but with the world in general) is when people attempt to nudge me or urge me or dragoon me into saying or agreeing with things that I prefer not to say or to agree with.

A motive is personal and subjective. An agenda is public and objective. It’s really a matter of emphasis and tone.

May the Lord be with you both.

Wow — I guess I hit a fundamentalist-evangelical nerve.

No one knows what Francis Thompson was thinking when he wrote “The Hound of Heaven.” You’d have to ask him, and he’s not around. Every one of Mr. Rizley’s rhetorical questions assumes that I (or any literary critic) must accept the notion that every religious poem written by a Christian will have a didactic-evangelical purpose. Well, that’s an incorrect assumption. Mr. Rizley has spent most of his life giving sermons, and this “deformation professionelle” makes him think that every time a Christian opens his mouth or picks up a pen it’s to imitate Saint Paul.

Does every Jew who writes a poem want to convert his readers to Judaism?

Does every Hindu who writes a poem want to convert his readers to Hinduism? Does every Buddhist who writes a poem want to convert his readers to Buddhism?

I ask anyone who wonders about this to read my essay on Creativity, Originality, and Eccentricity, which was just republished in Journal XI of the SCP. There I point out that every good poem contains some ineradicable traces of its origin, in the personality, habits, and beliefs of its author. That’s what “originality” properly means. So quite naturally a poem written by a believing Christian, if it is on a specifically religious subject, will have some traces of his views. But that is NOT NECESSARILY THE CASE. I have written a poem questioning the value of missionary work (“The Missionary’s Position”) even though I believe missionary work is valuable and meritorious.

Why did I write it? Because poetry is a licensed zone of hyper-reality, in which anything can be said if it is said well and effectively. And the words and inspiration for the poem just came to me. My grandfather was Freemason and a Deist, and I translated his sonnet on “Easter,” which questions the value of redemption itself. Why? Because it was an excellent sonnet, even though I disagreed with its skepticism. I also write poems of a sexually risque nature (like the one on Marguerite Steinheil) to clear the air of what is sometimes an insufferable sanctimoniousness.

I myself have written plenty of poems on religious subjects from my hard-right Tridentine Roman Catholic point of view. “The Lilacs on Good Friday,” “London Charterhouse,” “St. Anthony and the Demons,” “Epuration,” “A Token of Espousal” — I could list them ad infinitum. And I have made it abundantly clear, in many poems and comments at this site, what I think of the current subversion and corruption of the institutional Catholic Church at this woeful time, under a heretical Antipope. So I have always made my religious views quite clear. But I don’t try to push them on people, like some Amway dealer.

Rizley ends his long post by saying “However, the value of what they [religious poets] write, from a literary standpoint, must be judged by literary standards that apply across the board to all poetry.”

That is really no different from what I have been saying. A lousy religious poem is not saved by its pious good intentions. And I have never said that a Christian poet may not write whatever he likes, with whatever intention he may have. I have said that if he is a serious poet, his larger intentions must be aesthetic and stylistic, NOT evangelical. A poem is an end in itself, not a means to some other end.

My main argument in this dispute has been political, not religious. Just as I am wary of when left-liberals come here to colonize the site for their aims, so also am I wary when religionists of any denomination come here to gently and slowly push the site into a specific doctrinal direction.

I worked for a plumbing company fifty years ago. Once I told my boss that I thought there were a few things that needed to be changed. He told me that when I had my own company I could do it my way. So I started my own company. Turned out he was right about everything.

SCP is a big tent for anyone who agrees with our Mission Statement. Can poets have their own mission/agenda? Of course, as long as they understand and appreciate that, within these walls, Evan is the boss.

When we help Evan accomplish his mission, many of our own missions will also be accomplished.

Evan is the absolute boss. No questions at all about that.

Well said! I look through other poetry magazines to publish my work, and so much of what a lot of them publish is navel-gazing prose (bonus points if it expresses the woke worldview) with random line breaks (some don’t even bother with line breaks), which I can’t even stand to read through. It’s interesting to see the thought process of how it happened. It seems to be more a product of today’s narcissistic culture than anything else.

I’ve already expressed my only issue with the ideas in another comment.