.

Newman, Alone

Newman, thirty, alone, asleep in bed,

Groans, yearning for his mother, years now, dead—

Alive, her vivid female acts above

Had served as lodestar for his childish love.

The women he’d seduced, while far from God,

were back to haunt his dreams, with sneers, eyes hard

(He’d vowed, that week, to give up all sex, in

A hope for holiness, but in dreams it vexed him).

They’d formed a ring, him naked in the center,

All pointing, smirking, with a mocking banter:

Though striving, while awake, to keep his thoughts pure,

He had a hard-on—though they’d helped, he was sure.

Despite his earnest wish they would ignore it,

They all instead were mocking him for it.

A smile had dried embarrassed on his face,

realizing none would care to shroud his disgrace.

Desperate for help, a love without reprove,

To negate his sin, just have it be removed,

He turned and fled from their rich house outdoors

And staggered, pained, through fields filled with the poor.

Despised in life, they rested now at peace,

on sunlit hills, beneath the trees, at ease.

The sun, for them calm, warm, for him was harsh:

It blinded, blazed, and burned; his throat ached, parched.

He knew, though blinded in its glare of day,

That while he stayed, his sin was burned away

If only he could find its heart of love—

One true embrace he’d never let go of.

And though he knew he’d never been there before,

And only half-knew who he was looking for,

He was drawn like a dog tracking home for weeks,

Long lost without a whiff of what he seeks,

To that pure love, distinct from every other:

No son needs to see her to know his mother.

As a skiff would drift to shore, knowing she’d died,

He knelt to feel her hug, and woke, and cried.

.

.

Adam Wasem is a writer and rare bookseller living in suburban Salt Lake City, Utah.

Beautiful and haunting.

Thank you, Rohini. I’m glad you found it moving.

I hope this isn’t John Henry Newman.

No, no relation. Just a character name chosen for its relevance to the theme.

Not that it would necessarily be a bad thing if it were John Henry N. After all, we all need rescuing from our sins, and some of the greatest Christian literature (think the “Confessions”) has come from sordid lives that were upended by the work of the Holy Spirit.

I certainly agree with you about the “Confessions.” I do think Augustine’s repudiation of the carnal human nature therein has been somewhat misinterpreted since, with hair shirts and self-flagellation and so forth. This poem is perhaps a baby step in a corrective direction for those misinterpretations, as you surmised–i.e. how to approach opposite-sex relations in a modern carnal age, as compared to an ancient one.

Somewhere Augustine muses–either in “Confessions” or “The City of God,” I can’t remember where–about how much better it would be to bear children through the movements of the will rather than through the hydraulics of lust (I’m paraphrasing), and I’ve often pondered that idea, as well as Jesus’ instruction in Matthew 22:30, about those at the Resurrection neither marrying nor being given in marriage. No doubt both of those passages influenced this poem.

Augustine’s key objection to “lust” (ordinary sexual desire, called “luxuria” in Latin), is that succumbing to it means one’s will is overpowered by a bodily need. This would be true even for a married couple experiencing orgasm. Augustine’s background was heavily Platonic, and for the higher intellectual power of will to be overcome by the lower bestial power of concupiscence would be shameful and unseemly to him. (Whether sex between a married couple was “sinful” was an open question in the medieval period, but the voice of the Wife of Bath makes it very clear that many persons didn’t care a fig for what Augustine believed.)

There is no marriage or sexual activity at all in heaven. That’s pretty clear from scripture.

Interesting on so many levels, a son searching for the mother that seems to have died in childhood, filling the void as an adult with womanizing, searching in face after face, finally being able to make loving contact with his mother again in his dreams. A micronovella in itself.

The poem seems to turn on this line, “And staggered, pained, through fields filled with the poor…” Turning to the poor being unable to fill the void in his life with women, and not to even the living poor, the dead poor, but through them he poetically makes his way back to the nurturing love of a mother, a wholly sacred love.

Thank you for your kind appreciation, Alan, and your picking up on the poem’s multilayeredness. Dream narratives seem to provide opportunities for dichotomy like no other form. I like your term “micronovella” also; there’s a lot going on, and for you not to have registered a complaint about its extent of content heartens me that its “stuffedness” didn’t veer fatally into the overstuffed. The “poor” in the poem I meant to be contrasted with his ex-paramours’ “rich house,” and to call to mind the “poor in spirit,” in Matthew 5:3, who possess this particular vision of the “kingdom of heaven,” that Newman stumbles into. It is a vision of paradise, after all, a place where he can, in a fit of fortune, visit, but where he ultimately, grievously, can’t stay.

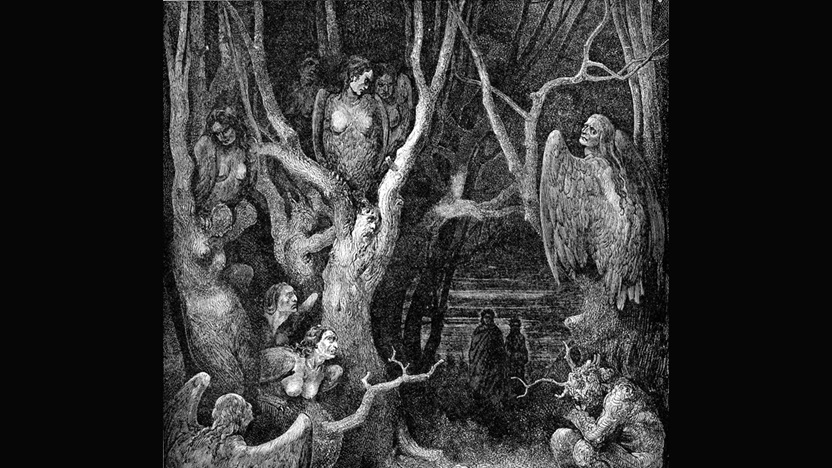

I like dream narratives and a shout out to Evan for a perfect graphic to go with this. I liked the first two lines best, actually. There’s a melodic punch to them that I’m musing over. The title derailed me, as I thought initially of Seinfeld’s Newman. Didn’t take long to get over that, of course, as the poem progressed. To me this was a blueprint for shame (Bradshaw’s thing). Hope to see more.

Oh, one more thought/question. Many lines have a great number of monosyllable words in them: Was that deliberate for effect, or just what the muse was offering?

Thank you, Daniel. Yes, it’s hard to think of a better illustrator here than Doré, isn’t it? Evan just seems to have a knack for it, among his many other talents. And the first two lines are pretty punchy, aren’t they? I liked how the first line reads like a rundown in a singles ad or (nowadays) online dating profile, contrasted with the emotional distress of the second line, along with all the internal rhyme (“alone” and “Groans”) and effects (“yearning” and “years”) tying everything together.

And yes, there is shame involved, of course, regret for one’s past, tied up with a longing for a primal innocence that’s lost and currently unattainable, embodied by the mother. I’m not sure what you mean by “Bradshaw’s thing,” but you will very likely see more in this vein from me, if Evan deems it worth posting. Having been myself deeply convicted as a Christian in my heart at 21 and having lost my own mother at 25, no doubt these two events will continue to inform whatever I produce.

The monosyllabic tendencies of the lexicon I would attribute to the yearning for the primal innocence I mentioned above. The closer Newman gets to the poem’s “heart of love,” the simpler and more childlike the language gets. As to whether it was deliberate for effect, or just what the muse was offering, I would have to say, “yes.” The Spirit offers me the ideal lines, and then it’s up to me to dictate them properly. Sometimes I do well, sometimes not so well.

No apologies are necessary; the poem stands on its own.

I didn’t intend to apologize for the poem. Certainly not to another sinner like myself. It’s unfortunate that it may have come off that way. Shame, regret and repentance are just as worthy of being dramatized as any other human emotion, if not more so. Thank you very kindly for the vote of confidence, C.B.

I was excited to read another work of yours. This is a great narrative poem, and demonstrates how well the modern idiom works in the classical form. Rhyming “sex, in” with “vexed him” was a particularly clever turn, and I can’t say I’ve read the word “hard-on” in a poem with rhyme and meter before. I love the inner drama the poem has — really without any dialogue — and the cathartic ending that puts all the turbulence to rest.

Thank you, Adam. I’m glad you enjoyed it, and I appreciate your accolades regarding my fusion of idiom and form. I do fear sometimes that my contemporary idiom isn’t “classical” enough for the Classical Poets Society, not to mention my quotidian subject matter, and I’m relieved to hear that it comes across successfully, at least with you. I used “hard-on” in that vein, as I am firmly of the belief that the “earthier” terms in our language are just as worthy of inclusion in poetry as the loftier. I owe it to the truth to be as candid with the reader as I am with myself, and moreover, “he had a hard-on” is objectively better, poetically, in this context than “he had an erection.” And I originally began writing as a short story writer and aspiring novelist; thanks to my amateur actress mother and novel-loving father, drama and narrative are ineradicably in my blood.