.

Dialogue on a First Grade

Science Textbook

Many spiritual traditions throughout history

have perceived all things, animate and

inanimate, as living.

“Usually religions teach people to believe

spiritually so as to achieve material

transformation, whereas science tells people

to perceive materially so as to elicit people’s

spiritual trust and support.” —Master Li

TEACHER

Now open up your book to page fifteen

And answer me, young sir: which one’s alive?

STUDENT

Is this a first-grade book? What do you mean?

I hope I do not look like I am five.

TEACHER

Well, humor me: describe now what you see.

STUDENT

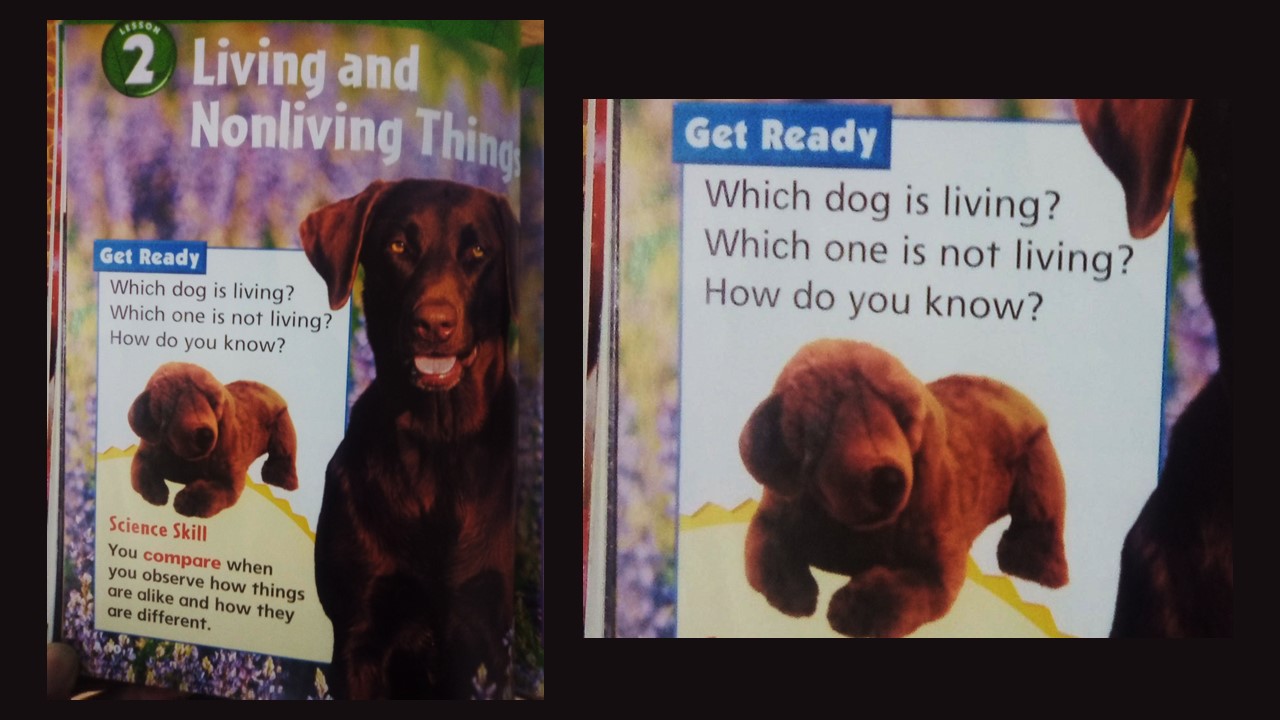

Colors so bright, fonts so big they blind…

But once I squint it’s pure mundanity:

A picture of a dog is what I find,

And next to it a plush stuffed animal.

It says to choose which is the living thing.

TEACHER

Of course you choose the one that can sit tall,

Roll over, fetch, and bark when doorbells ring.

STUDENT

Of course.

TEACHER

And now suppose a third dog’s there too—

A dead one. Does this body live or not?

STUDENT

Not. It does not grow nor breathe nor care to

Eat; its blood stops cold and starts to rot.

TEACHER

And if we take shed fur, perhaps a limb

Cut off by accident: is that alive?

STUDENT

Again, it has no life after the trim.

TEACHER

Before on my conclusion we arrive

Let us back up. Why do we not compare

An apple to an orange, as they say?

STUDENT

To properly compare requires a pair

Alike or else the whole thing goes astray;

For if the judge is fond of apples but

Not oranges, we’ll not know the orange’s worth.

TEACHER

So too we can’t compare this breathing mutt

To one that in a toy store had its birth.

The latter is a tiny severed piece

Of something that is larger and is living—

The Family, let us call it, can increase

In size or decrease by a member’s leaving.

In other words, it grows, it feeds, it feels.

The parents and the children are the soul

That finds itself content at Family meals

Or otherwise when gathering as a whole.

Their house and their possessions are the body

Which lives as long as Family members breathe.

The toy is then a living thing more truly

Than is a single dog with deadly teeth;

For cross the dog enough, perhaps he’ll bite,

But cross the Family and you’ll face the law.

A dog may greet you and his eyes burn bright;

The Family hosts you with a feast to awe.

STUDENT

But don’t you think this will confuse the child?

TEACHER

Oh not at all, in fact they’re more aware

That everything within the world is filled

With life that’s busy living everywhere.

And so the Education found today

Removes the wisdom of a spiritual plane

Innate within a child’s simple way

Replacing it with truths reduced and plain

It can control and understand with ease.

It gives you these, producing wonders

Of the modern world that help or please.

But with this proof it leads you on to blunders

Thinking that no God exists nor Heaven.

It gives you things and then expects your faith.

Tradition starts with all the things you haven’t.

You have no proof, just faith, and walk that path;

In time you will perceive a holy realm

That though invisible can overwhelm.

.

.

Evan Mantyk teaches literature and history in New York and is Editor of the Society of Classical Poets.

Powerful poem on the sad state of affairs in the decaying American education system juxtaposed with what should be! This is a scholarly creative, and conversational poem that attracted my attention and admiration. I concur wholeheartedly with the message imbued by the teacher.

Thank you, Roy. It’s a weird piece so I’m glad you could connect with it!

This is a wonderful and fascinating poem, Evan, which pits material values against spiritual values and articulates abstractions in an entertaining and enlightening way. I must confess, I’m not totally sure of my understanding of why the toy dog is more “alive” than the actual living dog, but it resonates with me in the same way as when one says that an author’s work which is essentially immortal is far more alive than the author will ever be. The same may be said of martyrs who live on in a way common people never can. And the toy dog may live in a way — and for longer — than the real dog. I am reminded here of The Velveteen Rabbit.

Your discussion of the pitfalls of the modern classroom are especially observant and important: the blunders of modern education — especially concerning young children — are particularly heinous since children are now indoctrinated into atheism, gender confusion and critical race theory. They are being weaponized. This exists, but it is not the focus of your poem. Rather, the point of your poem seems to be how to see more deeply than materialists can manage. The final lines of your poem so beautifully describe the “haven’ts” that lead to tradition and faith. This is one special teacher who can bypass all the blunders of most modern teachers and impart to a child the foundation for true knowledge, wisdom and faith.

Thank you, Brian. As I mentioned above to Roy, it’s a weird piece so I’m glad you could connect with it. The idea is that the stuffed animal is part of a larger being (we can conjecture some family) just as a hair or piece of a body is part of a person. If we compare an entire human family to a single dog (presuming the dog to be a stray), then one might see it as relatively lower in worth, perhaps legally or socially, than a family of human beings. Now if the dog is owned by a family then it gets more complicated and that comparison doesn’t work.

What this poem is meant to get at is that our society and education have generally accepted a particular philosophy of science, what some might call reductionism, which looks at reducing things to their smallest units, cells, DNA, molecules, proton numbers etc. and sees that as ultimate objective truth. This philosophy is highly pragmatic but essentially flawed since it operates independent of God, Heaven, good and evil etc. However, if we do the reverse and expand rather than reduce the paradigm underlying our philosophy of science then what we are dealing with is much harder to study, but exists in a logical manner in something more like fields (see the work of very accomplished scientist Rupert Sheldrake and his theory of morphic fields). The fields are living aggregates of alike and associated parts. Western civilization, America, New York, the family etc. Childrens’ perspectives, poetry, the humanities, and to some extent social sciences already operate on this principle but are always subsidiary in academic contexts to hard sciences based on reductionism. My point is that the reductionist path as an underlying philosophy of science is deeply entrenched, is counterintuitive, and is quite possibly misleading, false, and destructive.

Well, I think the poem can be subject to varying interpretations. First let me say that right from the start the student seems to be very bright and articulate. And he is somewhat miffed at having to look at a first-grade science book, so we can assume that he is well beyond that grade level. So there must be some special reason behind the teacher’s asking him to comment on it.

And right up to line 27 the student’s answers are concise, clear, unconfused, and perceptive, at least as far as I can see. In fact, the teacher’s questions remind me of Socrates in some of the Dialogues, where he slyly sets up someone for a logical punch by leading him on with simple questions.

The teacher’s longer discourse that follows, on the other hand, strikes me as a kind of “chop-logic,” as Shakespeare puts it, since I cannot quite follow what his argument (about a living dog and a toy dog) is trying to say, and how this relates to a human family. Also, it is somewhat abstract and cloudy.

So my first impulse was to think that the poem is an attempt to satirize the way in which too many teachers spread gaseous clouds of confusion in the minds of students. In that reading, student is the GOOD guy, and teacher is the BAD guy. But Brian’s reading suggests that this is incorrect — the teacher here is trying to show the student the ways in which certain types of education are harmful, and the teacher does it by bringing up the “apples and oranges” point. In that reading, the student is GOOD by being intelligent and sensible, and the teacher is GOOD by trying to illustrate that foolish comparisons are pernicious.

However, perhaps Evan Mantyk is attempting to illustrate a point from Li Hongzhi that is not directly mentioned here. In that case, maybe a short epigraph would he a helpful directional guide to the reader.

Thank you, Joe. You are absolutely right about the need for a clarifying epigraph, which I’ve added. Also, I’ve commented to Brian above in more detail on what the point of this piece was.

I certainly hope that this dialogue is not true to any actual conversations you might have had with your pupils, but I’ll bet it comes fairly close. I’m confounded by the ambiguity that attends any attempt to rationalize the relationship between reality and perception. What we give to living animals is a simulacrum of our aspirations and settled beliefs, and we can do the same for stuffed animals. Every child has a sleep-time favorite or two that he or she cannot do without. So it is that we project our humanity onto animal creatures, living or manufactured.

Well said, Kip! “the ambiguity that attends any attempt to rationalize the relationship between reality and perception”: exactly.

A ‘weird’ poem indeed, but a significant one: the moderns start from the irrational notion that by explaining rationality to a child they (the child) will thereby imbibe, first, morality, and second, confidence (‘with faith’) in life. Neither outcome is true, any more than the original supposition; so the explosion of immorality (aka wickedness) and increasing suicide in the young. As your poem points out: the blunder could be called elementary to not believe in God and heaven. Excellent work.

This is a fascinating piece, Evan. The idea that “life” is something more expansive than the mere presence of biological processes and more akin to Sheldrake’s morphic fields is an interesting insight and one which I think rings true given our experience of the world. As you rightly point out, children intuitively get this – they understand the toy dog is of a different order of being as the real dog but they do not deny it life because they know that being alive is an activity and that anything which participates in that activity can be said to be “alive” in some way. Interpreting this action in light of Sheldrake rather than (*yawn*) Freud offers much food for thought.